February 09, 2020

Russian Dolls - a design pattern for end to end secure transactions

This is a great research attack on a SWIFT-using payment institution (likely a British bank allowing the research to be conducted) from Oliver Simonnet.

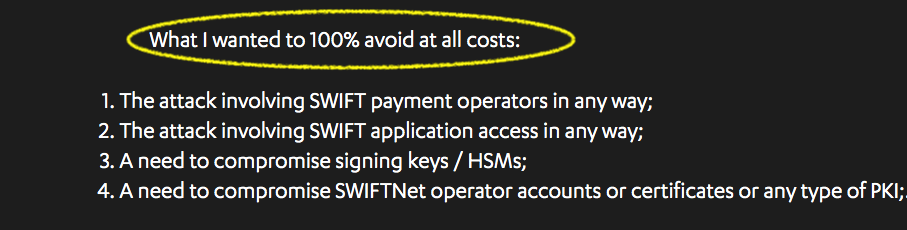

But I was struck by how the architectural flaw leapt out and screamed HIT ME HERE! 1/17

@mikko We were able to demonstrate a proof-of-concept for a fraudulent SWIFT payment message to move money. This was done by manually forging a raw SWIFT MT103 message. Research by our Oliver Simonnet: labs.f-secure.com/blog/forging-swift-mt-payment-messages

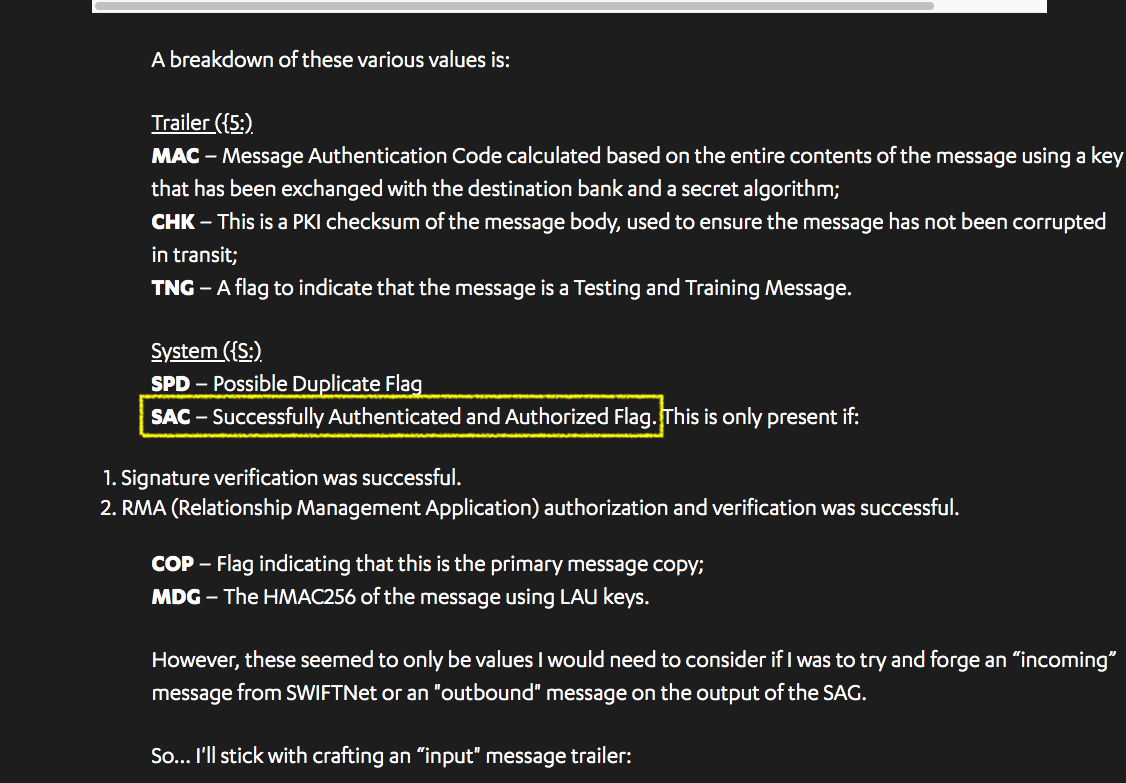

Here’s the flaw: SAC is a flag that says signature verification and RMA (Relationship Management Application) authorisation and verification was successful.

Let me say that more clearly: SAC says verification is done. 2/17

The flaw is this: the SAC isn’t the authorisation - it’s a flag saying there was an auth. Which means, in short SWIFT messages do not carry any role-based authorisations.

They might be authorised, but it’s like they slapped a sticker on to say that.

Not good enough. 3/17

It’s hard to share just how weird this is. Back in the mid nineties when people were doing this seriously on the net, we invented many patterns to make digital payments secure, but here we are in the ‘20s - and SWIFT and their banks haven’t got the memo. 4/17

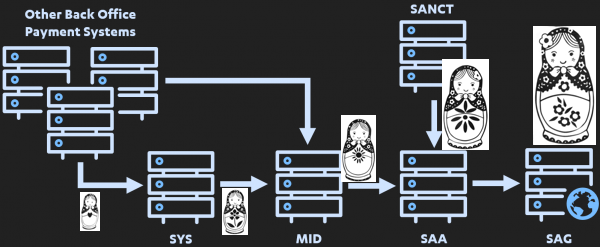

They’ve done something: LUAs,MACs,CHKs.

But these are not authorisations over messages, they’re handshakes that carry the unchanged message to the right party. These are network-security mechanisms, not application-level authorisations - they don’t cover rogue injection. 5/17

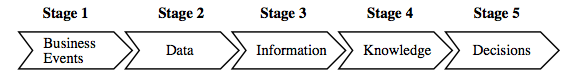

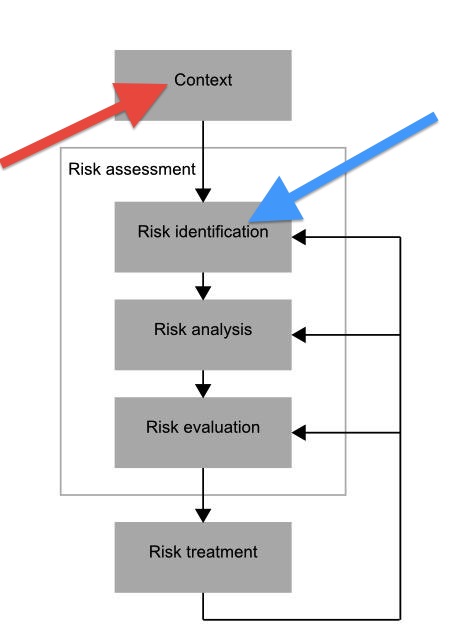

Let’s talk about a solution. This is the pattern that Gary and I first explored in Ricardo in mid-nineties, and Chris Odom put more flesh on the design and named it:

Russian Dolls

It works like this: 6/17

Every node is an agent. And has a signing key.

The signing key says this message is authorised - not access controlled, not authentically from me but authorised by me and I take the consequences if it goes wrong. 7/17

Every node signs their messages going out at the application level.

(as an aside - to see this working properly, strip out LUAs and encryption, they’re just a distraction. This will work over the open net, over raw channels.) 8/17

Every node receives inbound messages, checks they are authorised, and only proceeds to then process authorised messages. At that point it takes over responsibility - this node is now responsible for the outcomes, but only its processing, bc it has an authorised instruction. 9/17

The present node now wraps the inbound message into its outbound message, and signs the whole message, including the received inbound.

The inbound is its authorisation to process, the outbound is an authorisation to the next node.

Sends, to the next node. 10/17

Repeat. Hence the message grows each time. Like Russian Dolls, it recursively includes each prior step. So, to verify:

take the message you received, check it is authorised.

THEN, pull out its inner message, and verify that.

Repeat all the way to the smallest message. 11/17

This solves the SWIFT design weakness: firstly there is no message injection possible - at the message layer.

You could do this over the open net and it would still be secure (where, secure means nobody can inject messages and cause a bad transaction to happen). 12/17

2- as the signing key is now responsible as a proxy for the role/owner of that node, the security model is much clearer - PROTECT THAT KEY!

3- compromise of any random key isn’t enough bc the attacker can’t forge the inbound.

For top points, integrate back into the customer. 13b/17

OK, if you’ve followed along & actually get the pattern, you’re likely saying “Why go to all that bother? Surely there is a better, more efficient way…”

Well, actually no, it’s an end to end security model. That should be the beginning and end of the discussion. 14/17

But there is more: The Russian Dolls pattern of role-based authorisation (note, this is not RBAC) is an essential step on the road to full triple entry:

"I know that what you see is what I see."

15/17

In triple entry, the final signed/authorised message, the Big Babushka, becomes the 'receipt'. You:

(a) reflect the Babushka back to the sender as the ACK, AND(b) send it to SWIFT and on to the receiving bank.

Now, the receiving bank sees what client sender sees. 16/17

And you both know it. Muse on just what this does to the reconciliation and lost payments problem - it puts designs like this in sight of having reliable payments.

(But don’t get your hopes up. There are multiple reasons why it’s not coming to SWIFT any time soon.)

17/17

March 16, 2019

Financial exclusion and systemic vulnerability are the risks of cashlessness

"Access to Cash Review" confirms much that we have been warning of as UK walks into its future financial gridlock. From WolfStreet:

Transition to Cashless Society Could Lead to Financial Exclusion and System Vulnerability, Study Warnsby Don Quijones • Mar 14, 2019

“Serious risks of sleepwalking into a cashless society before we’re ready – not just to individuals, but to society.”

Ten years ago, six out of every ten transactions in the UK were done in cash. Now it’s just three in ten. And in fifteen years’ time, it could be as low as one in ten, reports the final edition of the Access to Cash Review. Commissioned as a response to the rapid decline in cash use in the UK and funded by LINK, the UK’s largest cash network, the review concludes that the UK is not nearly ready to go fully cashless, with an estimated 17% of the population – over 8 million adults – projected to struggle to cope if it did.

Although the amount of cash in circulation in the UK has surged in the last 10 years from £40 billion to £70 billion and British people as a whole continue to value it, with 97% of them still carrying cash on their person and another 85% keeping some cash at home, most current trends — in particular those of a technological and generational bent — are not in physical money’s favor:

Over the last 10 years, cash payments have dropped from 63% of all payments to 34%. UK Finance, the industry association for banks and payment providers, forecasts that cash will fall to 16% of payments by 2027.

...

Curiously, several factors are identified which speak to current politics:

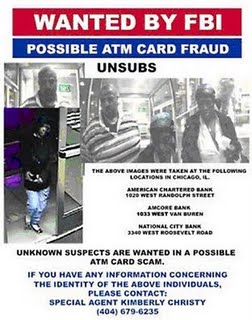

- "ATMs — or cashpoint machines, as they’re termed locally — are disappearing at a rate of around 300 per month, leaving consumers in rural areas struggling to access cash."

- "The elderly are widely perceived as the most reliant on cash, but the authors of the report found that poverty, not age, is the biggest determinant of cash dependency."

- "17% of the UK population – over 8 million adults – would struggle to cope in a cashless society."

- "Even now, there’s not enough cash in all the right places to keep a cash economy working for long if digital or power connections go down, warns the report."

I have always thought that Brexit was not a vote against Europe but a vote against London. The population of Britain split, somewhere around 2008 crisis into rich London and poor Britain. After the crash, London got a bailout and the poor got poorer.

By 2016-2017 the feeling in the countryside was palpably different to London. Even 100km out, people were angry. Lots of people living without the decent jobs, and no understanding as to why the good times had not come back again after the long dark winter.

Of course the immigrants got blamed. And it was all too easy to believe the silver-toungued lie of Londoners that EU regulation was the villain.

But London is bank territory. That massive bailout kept it afloat, and on to bigger and better things. E.g., a third of all European fintech startups are in London, and that only makes sense because the goal of a fintech is to be sold to ... a bank.

Meanwhile, the banks and the regulators have been running a decade long policy on financial exclusion:

"And it’s not all going in the right direction – tighter security requirements for Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering) (AML), for example, actually make digital even harder to use for some.

Note the politically cautious understatement: KYC/AML excludes millions from digital payments. The AML/KYC system as designed gives the banks the leeway to cut out all low end unprofitable accounts by raising barriers to entry and by giving them carte blanche to close at any time. Onboarding costs are made very high by KYC, and 'suspicion' is mandated by AML: there is no downside for the banks if they are suspicious early and often, and serious risk of huge fines if they miss one.

Moving to a cashless, exclusionary society is designed for London's big banks, but risks society in the process. Around the world, the British are the most slavish in implementing this system, and thus denying millions access to bank accounts.

And therefore jobs, trade, finance, society. Growth comes from new business and new bank accounts, not existing ones. Placing the UK banks as the gatekeepers to growth is thus a leading cause of why Britain-outside-London is in a secular depression.

Step by painful step we arrive at Brexit. Which the report wrote about, albeit in roundabout terms:

Government, regulators and the industry must make digital inclusion in payments a priority, ensuring that solutions are designed not just for the 80%, but for 100% of society.

But one does not keep ones job in London by stating a truth disagreeable to the banks or regulators.

January 11, 2019

Gresham's Law thesis is back - Malware bid to oust honest miners in Monero

7 years after we called the cancer that is criminal activity in Bitcoin-like cryptocurrencies, here comes a report that suggests that 4.3% of Monero mining is siphoned off by criminals.

A First Look at the Crypto-Mining Malware

Ecosystem: A Decade of Unrestricted Wealth

Sergio Pastrana

Universidad Carlos III de Madrid*

spastran@inf.uc3m.esGuillermo Suarez-Tangil

King’s College London

guillermo.suarez-tangil@kcl.ac.ukAbstract—Illicit crypto-mining leverages resources stolen from victims to mine cryptocurrencies on behalf of criminals. While recent works have analyzed one side of this threat, i.e.: web-browser cryptojacking, only white papers and commercial reports have partially covered binary-based crypto-mining malware. In this paper, we conduct the largest measurement of crypto-mining malware to date, analyzing approximately 4.4 million malware samples (1 million malicious miners), over a period of twelve years from 2007 to 2018. Our analysis pipeline applies both static and dynamic analysis to extract information from the samples, such as wallet identifiers and mining pools. Together with OSINT data, this information is used to group samples into campaigns.We then analyze publicly-available payments sent to the wallets from mining-pools as a reward for mining, and estimate profits for the different campaigns.Our profit analysis reveals campaigns with multimillion earnings, associating over 4.3% of Monero with illicit mining. We analyze the infrastructure related with the different campaigns,showing that a high proportion of this ecosystem is supported by underground economies such as Pay-Per-Install services. We also uncover novel techniques that allow criminals to run successful campaigns.

This is not the first time we've seen confirmation of the basic thesis in the paper Bitcoin & Gresham's Law - the economic inevitability of Collapse. Anecdotal accounts suggest that in the period of late 2011 and into 2012 there was a lot of criminal mining.

Our thesis was that criminal mining begets more, and eventually pushes out the honest business, of all form from mining to trade.

Testing the model: Mining is owned by BotnetsLet us examine the various points along an axis from honest to stolen mining: 0% botnet mining to 100% saturation. Firstly, at 0% of botnet penetration, the market operates as described above, profitably and honestly. Everyone is happy.

But at 0%, there exists an opportunity for near-free money. Following this opportunity, one operator enters the market by turning his botnet to mining. Let us assume that the operator is a smart and careful crook, and therefore sets his mining limit at some non-damaging minimum value such as 1% of total mining opportunity. At this trivial level of penetration, the botnet operator makes money safely and happily, and the rest of the Bitcoin economy will likely not notice.

However we can also predict with confidence that the market for botnets is competitive. As there is free entry in mining, an effective cartel of botnets is unlikely. Hence, another operator can and will enter the market. If a penetration level of 1% is non-damaging, 2% is only slightly less so, and probably nearly as profitable for the both of them as for one alone.

And, this remains the case for the third botnet, the fourth and more, because entry into the mining business is free, and there is no effective limit on dishonesty. Indeed, botnets are increasingly based on standard off-the-shelf software, so what is available to one operator is likely visible and available to them all.

What stopped it from happening in 2012 and onwards? Consensus is that ASICs killed the botnets. Because serious mining firms moved to using large custom rigs of ASICS, and as these were so much more powerful than any home computer, they effectively knocked the criminal botnets out of the market. Which the new paper acknowledged:

... due to the proliferation of ASIC mining, which uses dedicated hardware, mining Bitcoin with desktop computers is no longer profitable, and thus criminals’ attention has shifted to other cryptocurrencies.

Why is botnet mining back with Monero? Presumably because Monero uses an ASIC-resistant algorithm that is best served by GPUs. And is also a heavy privacy coin, which works nicely for honest people with privacy problems but also works well to hide criminal gains.

October 19, 2018

AES was worth $250 billion dollars

So says NIST...

10 years ago I annoyed the entire crypto-supply industry:

Hypothesis #1 -- The One True Cipher Suite In cryptoplumbing, the gravest choices are apparently on the nature of the cipher suite. To include latest fad algo or not? Instead, I offer you a simple solution. Don't.

There is one cipher suite, and it is numbered Number 1.

Cypersuite #1 is always negotiated as Number 1 in the very first message. It is your choice, your ultimate choice, and your destiny. Pick well.

The One True Cipher Suite was born of watching projects and groups wallow in the mire of complexity, as doubt caused teams to add multiple algorithms- a complexity that easily doubled the cost of the protocol with consequent knock-on effects & costs & divorces & breaches & wars.

It - The One True Cipher Suite as an aphorism - was widely ridiculed in crypto and standards circles. Developers and standards groups like the IETF just could not let go of crypto agility, the term that was born to champion the alternate. This sacred cow led the TLS group to field something like 200 standard suites in SSL and radically reduce them to 30 or 40 over time.

Now, NIST has announced that AES as a single standard algorithm is worth $250 billion economic benefit over 20 years of its project lifetime - from 1998 to now.

h/t to Bruce Schneier, who also said:

"I have no idea how to even begin to assess the quality of the study and its conclusions -- it's all in the 150-page report, though -- but I do like the pretty block diagram of AES on the report's cover."

One good suite based on AES allows agility within the protocol to be dropped. Entirely. Instead, upgrade the entire protocol to an entirely new suite, every 7 years. I said, if anyone was asking. No good algorithm lasts less than 7 years.

Crypto-agility was a sacred cow that should have been slaughtered years ago, but maybe it took this report from NIST to lay it down: $250 billion of benefit.

In another footnote, we of the Cryptix team supported the AES project because we knew it was the way forward. Raif built the Java test suite and others in our team wrote and deployed contender algorithms.

June 25, 2018

FCA on Crypto: Just say no.

Because it's Sunday, I thought I'd write a missive on that favourite depressing topic, the current trend of the British nation to practice economic self-immolation. I speak of course of the FCA's letter to the CEO.

Some many may be bemused and think that this letter shows signs of progress. No such. What the letter literally is, is the publication of a hitherto secret order sent to CEOs of banks to not bank crypto.

The instruction was delivered some time ago. Verbally. And deniably. The banks knew it, the FCA knew it, but all denied it unless under condition of confidentiality or alcohol.

Which put the FCA, the banks, and Britain into considerable difficulties - the FCA could neither move forward to adjust because there was no position to adjust, the British banks could not bank crypto because they were under instruction, and the British crypto-using public either got screwed by the banks or they left the country for Europe and places further afield.

(Oddly, it turns out that Berlin is the major beneficiary here, but that's a salacious distraction.)

After some pressure as the 'star chamber' process of business policy, it transpires a week ago that the FCA has come out of the cold and issued the actual instruction in writing. This is now sufficient to replace the secret instruction, so it represents a movement of sorts. We can now at least openly debate it.

However the message has not changed. To understand this, one has to read the entire letter and also has to know quite a lot about banks, compliance and the fine art of nah-saying while appearing to be encouraging.

The tone is set early on:

CRYPTOASSETS AND FINANCIAL CRIMEAs evidence emerges of the scope for cryptoassets1 to be used for criminal purposes, I am writing regarding good practice for how banks handle the financial crime risks posed by these products.

There are many non-criminal motives for using cryptoassets.

It's all about financial crime. The assumption is that crypto is probably used for financial crime, and the banks' job is to stop that happening. Which would logically set a pretty high bar because (like money, which is also used for financial crime) the use of crypto (money) by customers is generally opaque to the bank. But banks are used to being the frontline soldiers in the war on finance, so they will not notice a change here.

The problem is of course that it simply doesn't work. The bank can't see what you are doing with crypto, so what to do? When the banks ask customers what they do with the money, costs sky rocket, but the quality of the information doesn't increase.

There is therefore only one equilibrium in this mathematical puzzle that the FCA has set the banks: Just say no. Shut down any account that uses crypto. Because we will hold you for it and we will insist on no failures.

Now, if it was just that, a dismal letter conflating crime with business, one could argue the toss. But the letter goes on. Here's the smoking gun:

Following a risk-based approach does not mean banks should approach all clients operating in these activities in the same way. Instead, we expect banks to recognise that the risk associated with different business relationships in a single broad category can vary, and to manage those risks appropriately.

The risk-based approach!

Once that comes into play, what the bank reads is that they are technically permitted to use crypto, but they are strictly liable if it goes wrong. Because they've been told to do their risk analysis, and they've done their risk analysis, and therefore the risks are analysed which conflates with reduced to zero.

Which means, they can only touch crypto if they know . This knowledge being full knowledge not that other long-running joke called KYC. Banks must know that the crypto is all and totally bona fide.

But they generally have no such tool over customers, because (a) they are bankers and if they had such a tool (b) they wouldn't be bankers, they would be customers.

(NB., to those who know their history, anglo-world banks used to know their customers' business quite well. But that went the way of the local branch manager and the dodo. It was all replaced by online, national computer networks, and now AIs that do not manifestly know anything other than how to spit out false positives. NB2 - this really only refers to the anglo world being UK, USA, AU, CAN, NZ and the smaller followers. Continental banking and other places follow a different path.)

Back to today. The upshot of the relationship for regulator-bank in the anglo world is this: "risk-based analysis" is code for "if you get it wrong, you're screwed." Which latter part is code for fines and so forth.

So what is the significance of this, other than the British policy of not doing crypto as a business line (something that Berlin, Gibraltar, Malta, Bermuda and others are smiling about)? It's actually much more devastating that one would think.

It's not about just crypto. As a society, we don't care about crypto more than as a toy for rich white boys to play at politics and make money without actually doing anything. Fun for them, soap opera for observers but the hard work is elsewhere.

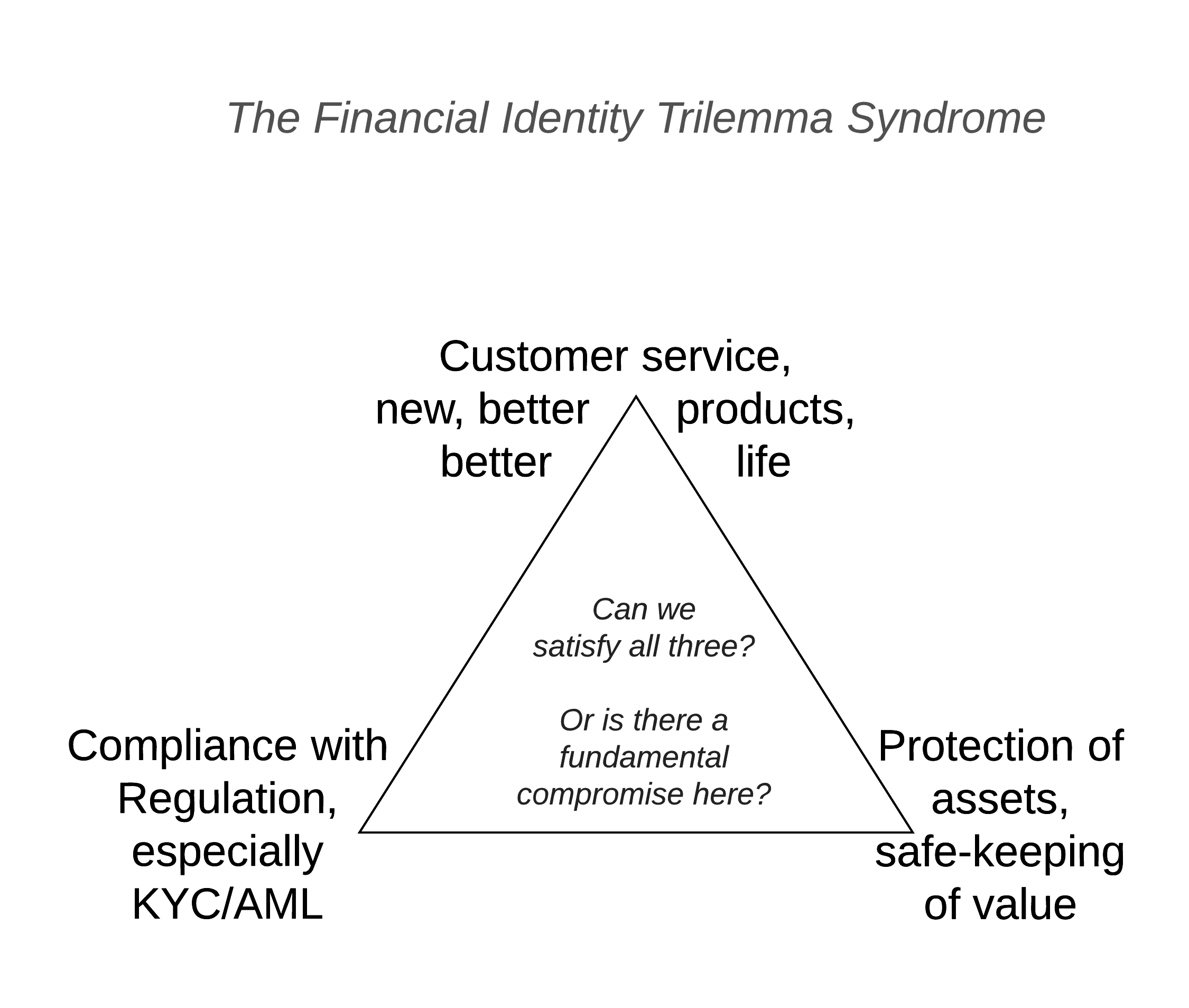

It's not in the crypto - it's in the compliance. As I wrote elsewhere, banks in the anglo world and their regulators are locked in a deadly embrace of compliance. It has gotten to the point where all banking product is now driven by compliance, and not by customer service, or by opportunity, or by new product.

In that missive on Identity written for R3's member banks, I made a startling claim:

FITS – the Financial Identity Trilemma SyndromeIf you’re suffering from FITS, if might be because of compliance. As discussed at length in the White Paper on Identity, McKinsey has called out costs of compliance as growing at 20% year on year. Meanwhile, the compliance issue has boxed in and dumbed down the security, and reduced the quality of the customer service. This is not just an unpleasantness for customers, it’s a danger sign – if customers desert because of bad service, or banks shed to reduce risk of fines, then banks shrink, and in the current environment of delicate balance sheets, rising compliance costs and a recessionary economy, reduction in bank customer base is a life-threatening issue.

For those who are good with numbers, you'll pretty quickly realise that 20% is great if it is profits or revenues or margin or one of those positive numbers, but it's death if it is cost. And, compliance is *only a cost*. So, death.

Which led us to wonder how long this can go on?

(youtube, transcript) Cost to compliance now is about 30% I’ve heard, but you pick your own number. Who works at a bank? Nobody, okay. That’s probably good news. [laughs] Who’s got a bank account? I’ve got bad news: if you do the compounding, in seven years you won’t have a bank accounts, because all the banks will be out of money. If you compound 30% forward by 20%, in seven years all of the money is consumed on compliance.

As I salaciously said at a recent Mattereum event on Identity, the British banks have 7 years before they die. That's assuming a 30% compliance cost today and 20% year on year increase. You could pick 5% now and 10% by 2020 as Duff & Phelps did which perversely seems more realistic as if the load is now 30% then banks are already dead, we don't need to wait until 100%. Either way, there is gloom and doom however society looks at it.

Now these are stupid numbers and bloody stupid predictions. The regulators are going to kill all the banks? Nah... that can only be believed with compelling evidence.

The FCA letter to the CEO is that compelling evidence. The FCA has doubled down on compliance. They have now, I suspect, achieved their 20% increase in compliance costs for this year, because now the banks must double down and test all accounts against crypto-closure policy. More.

We are one year closer to banking Armageddon - thanks, FCA.

What can we see here? Two things. Firstly, it cannot go on. Even Mark Carney must know that burning the banking village to save it is going to put Britain into the mother of all recessions. So they have to back off sometime, but when will that be? If I had to guess, it will be when major clients in the City of London desert the British banks, because no other message is heard in Whitehall or Threadneedle St. C.f., Brexit. Business itself isn't really listened to, or in the immortal words of the British Foreign Secretary,

Secondly, is it universal? No. There is a glimmer of hope. The major British banks cannot do crypto because the costs are asymmetric. But for a crypto bank that is constructed from ground up, within the FCA's impossible recipe, the costs are manageable. Such a bank would basically impose the crypto-compliance costs over all, so all must be in crypto. An equilibrium available to a specialist bank, not any high street dinosaur.

You might call that a silver lining. I call it a disaster. The regulators are hell bent on destroying the British economy by adding 20% extra compliance burden every year - note that they haven't begun to survey their costs, nor the costs to society.

After the collapse there will be green shoots, and we should cheer? Shoot me now.

Frankly, the broken window fallacy would be better than that process - we should just topple the banks with crypto right now and get the pain over with, because a fast transition is better than the FCA smothering the banks with compliance love.

But, obviously, the mandarins in Whitehall think differently. Watch the next seven years to learn how British people live in interesting times.

May 05, 2017

4th ed. Electronic Evidence now available

Stephen Mason has released the 4th edition of Electronic Evidence at

Electronic Evidence (4th edition, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies for the SAS Humanities Digital Library, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2017)http://ials.sas.ac.uk/digital/humanities-digital-library/observing-law-ials-open-book-service-law/electronic-evidence

Note that this is free to download, and it's a real law book, so we're entering a new world of accessibility to this information. The following are also freely available:

Electronic Signatures in Law (4th edition, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies for the SAS Humanities Digital Library, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2016)

http://ials.sas.ac.uk/digital/humanities-digital-library/observing-law-ials-open-book-service-law/electronic-signaturesFree journal: Digital Evidence and Electronic Signature Law Review

http://journals.sas.ac.uk/deeslr/

(also available in the LexisNexis and HeinOnline electronic databases)

For those of us who spend a lot of time travelling around, free digital downloads is a gift from heaven!

November 04, 2015

FC wordcloud

Courtesy of statistical analysis over this site by Uyen Ng.

October 25, 2015

When the security community eats its own...

If you've ever wondered what that Market for Silver Bullets paper was about, here's Pete Herzog with the easy version:

When the Security Community Eats Its Own

BY PETE HERZOG

http://isecom.org

The CEO of a Major Corp. asks the CISO if the new exploit discovered in the wild, Shizzam, could affect their production systems. He said he didn't think so, but just to be sure he said they will analyze all the systems for the vulnerability.

So his staff is told to drop everything, learn all they can about this new exploit and analyze all systems for vulnerabilities. They go through logs, run scans with FOSS tools, and even buy a Shizzam plugin from their vendor for their AV scanner. They find nothing.

A day later the CEO comes and tells him that the news says Shizzam likely is affecting their systems. So the CISO goes back to his staff to have them analyze it all over again. And again they tell him they don’t find anything.

Again the CEO calls him and says he’s seeing now in the news that his company certainly has some kind of cybersecurity problem.

So, now the CISO panics and brings on a whole incident response team from a major security consultancy to go through each and every system with great care. But after hundreds of man hours spent doing the same things they themselves did, they find nothing.

He contacts the CEO and tells him the good news. But the CEO tells him that he just got a call from a journalist looking to confirm that they’ve been hacked. The CISO starts freaking out.

The CISO tells his security guys to prepare for a full security upgrade. He pushes the CIO to authorize an emergency budget to buy more firewalls and secondary intrusion detection systems. The CEO pushes the budget to the board who approves the budget in record time. And almost immediately the equipment starts arriving. The team works through the nights to get it all in place.

The CEO calls the CISO on his mobile – rarely a good sign. He tells the CISO that the NY Times just published that their company allegedly is getting hacked Sony-style.

They point to the newly discovered exploit as the likely cause. They point to blogs discussing the horrors the new exploit could cause, and what it means for the rest of the smaller companies out there who can’t defend themselves with the same financial alacrity as Major Corp.

The CEO tells the CISO that it's time they bring in the FBI. So he needs him to come explain himself and the situation to the board that evening.

The CISO feels sick to his stomach. He goes through the weeks of reports, findings, and security upgrades. Hundreds of thousands spent and - nothing! There's NOTHING to indicate a hack or even a problem from this exploit.

So wondering if he’s misunderstood Shizzam and how it could have caused this, he decides to reach out to the security community. He makes a new Twitter account so people don’t know who he is. He jumps into the trending #MajorCorpFail stream and tweets, "How bad is the Major Corp hack anyway?"

A few seconds later a penetration tester replies, "Nobody knows xactly but it’s really bad b/c vendors and consultants say that Major Corp has been throwing money at it for weeks."

Read on for the more deeper analysis.

June 12, 2015

Issuance of assets, Genesis of transactions, contracting for swaps - all the same stuff

Here's what Greg Maxwell said about asset issuance in sidechains:

So the idea behind the issued assets functionality in Elements is to explicitly tag all of the tokens on the network with an asset type, and this immediately lets you use an efficient payment verification mechanism like bitcoin has today. And then all of the accounting rules can be grouped by asset type. Normally in bitcoin your transaction has to ensure that the sum of the coins that comes in is equal to the sum that come out to prevent inflation. With issued assets, the same is true for the separate assets, such that the sum of the cars that come in is the same as the sum of the cars that come out of the transaction or whatever the asset is. So to issue an asset on the system, you use a new special transaction type, the asset issuance transaction, and the transaction ID from that issuance transaction becomes the tag that traces them around. So this is early work, just the basic infrastructure for it, but there's a lot of neat things to do on top of this. *This is mostly the work of Jorge Tímon*.

Jorge documented all this back in 2013 in FreiMarkets with Mark Friedenbach. Basically he's adding issuance to the blockchain, which I also covered in principle back in that talk in January at PoW's Tools for the Future. As he covers issuance above, here's what I said about another aspect, being the creation of a new blockchain:

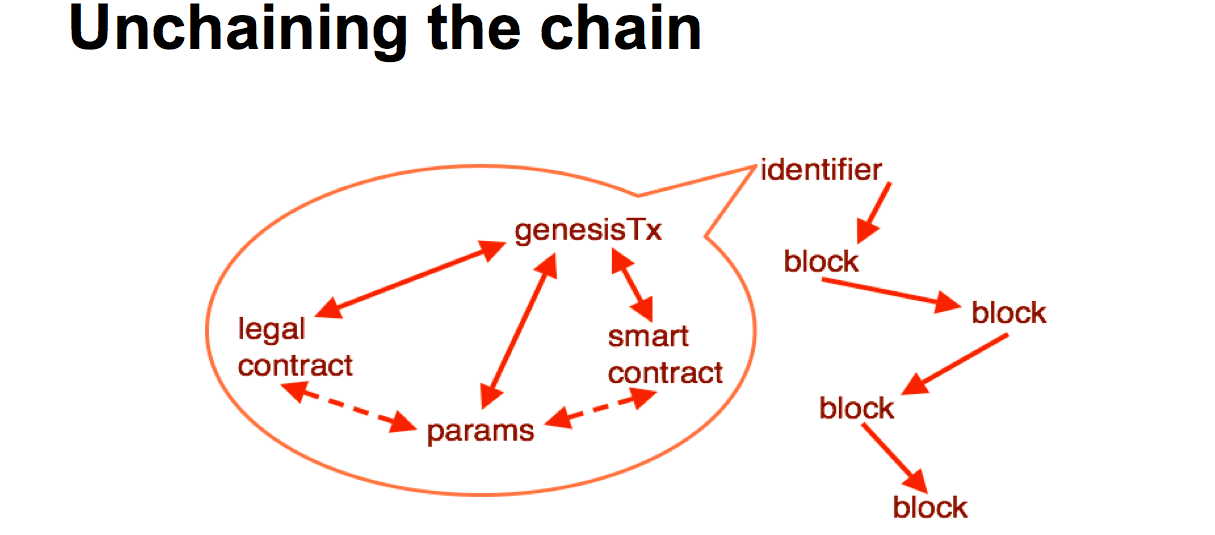

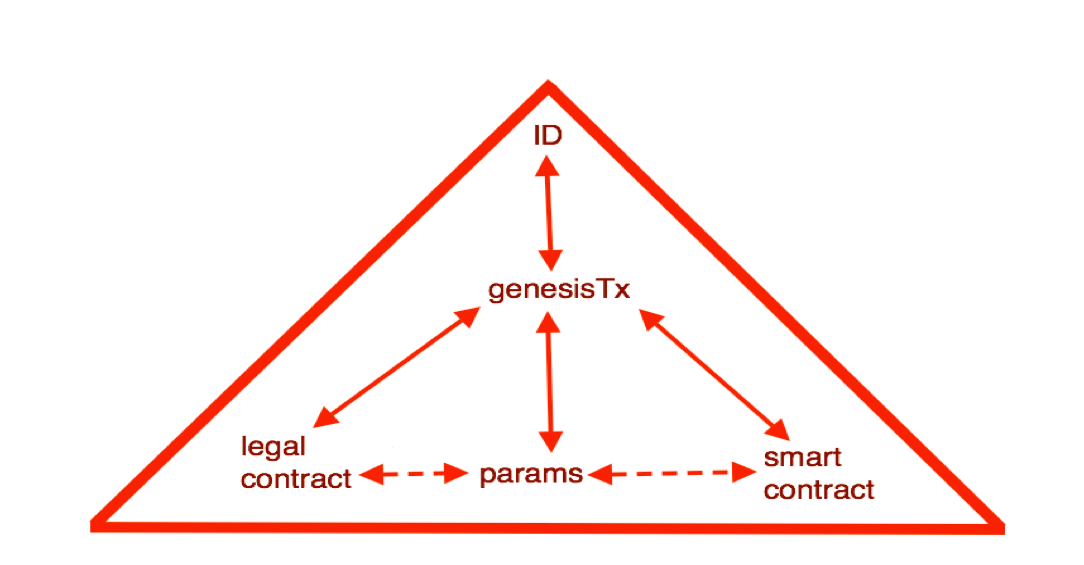

Where is this all going? We need to make some changes. We can look at the blockchain and make a few changes. It sort of works out that if we take the bottom layer, we've got a bunch of parameters from the blockchain, these are hard coded, but they exist. They are in the blockchain software, hard coded into the source code.

So we need to get those parameters out into some form of description if we're going to have hundreds, thousands or millions of block chains. It's probably a good idea to stick a smart contract in there, who's purpose is to start off the blockchain, just for that purposes. And having talked about the legal context, when going into the corporate scenario, we probably need the legal contract -- we're talking text, legal terms and blah blah -- in there and locked in.

We also need an instantiation, we need an event to make it happen, and that is the genesis transaction. Somehow all of these need to be brought together, locked into the genesis transaction, and out the top pops an identifier. That identifier can then be used by the software in various and many ways. Such as getting the particular properties out to deal with that technology, and moving value from one chain to another.

This is a particular picture which is a slight variation that is going on with the current blockchain technology, but it can lead in to the rest of the devices we've talked about.

The title of the talk is "The Sum of all Chains - Let's converge" for a reason. I'm seeing the same thinking in variations go across a bunch of different projects all arriving at the same conclusions.

It's all the same stuff.

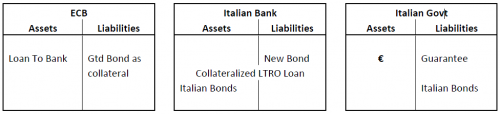

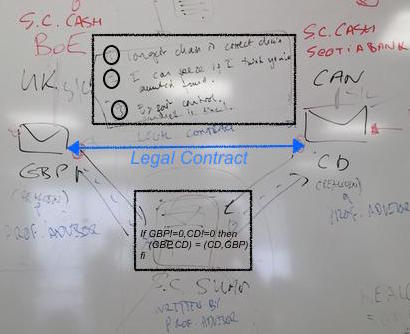

Here's today's "legathon" at UBS, at which the banking chaps tried to figure out how to handle a swap of GBP and Canadian Dollars that goes sour - because of a bug, or a lapse in understanding, or a hack, who knows? The two traders end up in court trying to resolve their difference in views.

In the court, the judge asks for the evidence -- where is the contract? So it was discovered that the two traders had entered into a legal contract that was composed of the prose document (top black box) and the smart contract thingie (lower black box). Then some events had happened, but somehow we hadn't got to the end. At this point there is a deep dive into the tech and the prose and the philosophy, law, religion and anything else people can drag in.

However, there's a shortcut. On that prose on the whiteboard, the lawyer chap who's name escapes me wrote 3 clauses. Clause (1) said:

(1) longest chain is correct chain

See where this is going? The judge now asks which is the longest chain. One side looks happy, the other looks glum.

Let's converge; on the longest chain, *if that's what you wrote down*.

June 05, 2015

Coase's Blockchain - the first half block - Vinay Gupta explains triple entry

Editor's Preamble! Back in 1997 I gave a paper on crowdfunding - I believe the first ever proper paper, although there was one "lost talk" earlier by Eric Hughes - at Financial Cryptography 1997. Now, this conference was the first polymath event in the space, and probably the only one in the space, but that story is another day. Because this was a polymath event, law professor who's name escapes Michael Froomkin stood up and asked why I hadn't analysed the crowdfunding system from the point of view of transaction economics.

I blathered - because I'd not heard of it! But I took the cue, went home and read the Ronald Coase paper, and some of his other stuff, and ploughed through the immensely sticky earth of Williamson. Who later joined Coase as a Nobel Laureate.

The prof was right, and I and a few others then turned transaction cost discussion into a cypherpunk topic. Of course, we were one or two decades too early, and hence it all died.

Now, with gusto, Vinay Gupta has revived it all as an explanation of why the blockchain works. Indeed, it's as elegant a description of 'why triple entry' as I've ever heard! So here goes my Saturday writing out Coase's first half block, or the first 5 minutes of Gupta's talk.

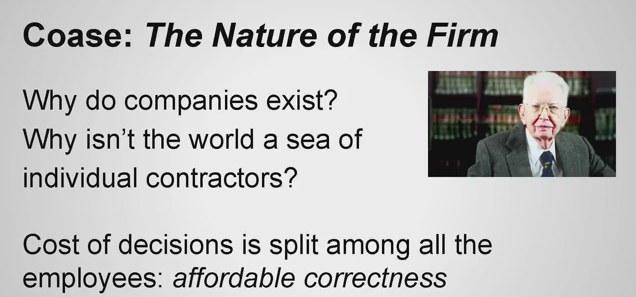

This is the title of the talk - Coase's Blockchain. Does anyone in the audience know who Ronald Coase was? No? Ok. He got the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1940. Coase's question was, why does the company exist as an institution? Theoretically, if markets are more efficient than command economies, because of a better distribution of information, why do we then recreate little pockets of command economy in the form of a thing you call a company?

This is the title of the talk - Coase's Blockchain. Does anyone in the audience know who Ronald Coase was? No? Ok. He got the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1940. Coase's question was, why does the company exist as an institution? Theoretically, if markets are more efficient than command economies, because of a better distribution of information, why do we then recreate little pockets of command economy in the form of a thing you call a company?

And, understanding why the company exists is a critical thing if you want to start companies or operate companies because the question you have to ask is why are we doing this rather than having a market of individual actors. And Coase says, the reason that we don't have seas of contractors, we've got structures like say IBM, is because making good decisions is expensive.

Last time you bought a telephone or a television or a car you probably spent 2 days on the Internet looking at reviews trying to make a decision, right? Familiar experience? All of that is a cost, that in a company is made by purchasing. Same thing for deciding strategy, if you're a small business person you spend a ton of time worrying about strategy, and all of those costs in a large company are amortised across the whole company. The company serves to make decisions and then amortise the costs of the decisions across the entire structure.

This is all essentially about transaction costs. Now, move onto Venture Capital.

This is all essentially about transaction costs. Now, move onto Venture Capital.

Paul Graham's famous essay "Black Swan Farming." What they basically say is venture capitalists have no idea what will or won't work, we can't tell. We are in the business of guessing winners, but it turns out that our ability to successfully predict is less than one in a hundred. Of a hundred companies we fund, 90 will fail, 10 will make about 10 times what we put into them, and one in about a thousand will make us a ton of money. One thousand to one returns are higher, but we actually have no way of telling which is which, so we just fund everything.

Even with their very large sample size, they are unable to successfully predict what will or will not succeed. And if this is true for venture capitalists, how much truer is it for entrepreneurs? As a venture capitalist, you have an N of maybe 600 or 1000, as an entrepreneur you've got an N of 2 or 3. All entrepreneurs are basically guessing that their thing might work with totally inadequate evidence and no legitimate right to assume their guess is any good because if the VCs can't tell, how the heck is the entrepreneur supposed to tell?

We're in an environment with extremely scarce information about what will or will not succeed and even the people with the best information in the world are still just guessing. The whole thing is just guesswork.

History of Blockchains in a Nutshell, and I will bring all this back together in time.

History of Blockchains in a Nutshell, and I will bring all this back together in time.

In the 1970s the SQL database was basically a software system that was designed to make it possible to do computation using tape storage. You know how in databases, you have these fixed field lengths, 80 characters 40 characters, all this stuff, it was so that when you fast-forwarded the tape, you knew that each field would take 31 inches and you could fast forward by 41 and a half feet to get to the record you needed next. The entire thing was about tape.

In the 1990s, we invent the computer network, at this point we're running everything across telephone wires, basically this is all pre-Ethernet. It's really really early stuff and then you get Ethernet and standardisation and DNS and the web, the second generation of technology.

The bridges between these systems never worked. Anybody that's tried to connect two corporations across a database knows that it's just an absolute nightmare. You get hacks like XML-EDI or JSON or SOAP or anything like that but you always discover that the two databases have different models of reality and when you interconnect them together in the middle you wind up having to write a third piece of software.

The N-squared problem. So the other problem is that if we've got 50 companies that want to talk to 50 companies you wind up having to write 50-squared interconnectors which results in an unaffordable economic cost of connecting all of these systems together. So you wind up with a hub and spoke architecture where one company acts as the broker, everybody writes a connector to that company, and then that company sells all of you down the river because it has absolute power.

As a result, computers have had very little impact on the structure of business even though they've brought the cost of communication and the cost of knowledge acquisition down to a nickel.

This is where we get back to Coase. The revolution that Coase predicted that computers should bring to business hasn't yet happened, and my thesis is that blockchains is what it takes to get that to run.

Editor again: That was Vinay's first 5m after which he took it across to blockchains. Meanwhile, I'll fork back a little to triple entry.

Recall the triple entry concept as being an extension of double entry: The 700 year old invention of double entry used two recordings as a redundant check to eliminate errors and surface fraud. This allowed the processing of accounting to be so reliable that employed accountants could do it. But accounting's double entries were never accepted outside the company, because as Gupta puts it, companies had "different models of reality."

Triple entry flips it all upside down by having one record come from an independent center, and then that record is distributed back to the two companies of any trade, making for 3 copies. Because we used digital signatures to fix one record, triply recorded, triple entry collapses the double vision of classical accounting's worldview into one reality.

We built triple entry in the 1990s, and ran it successfully, but it may have been an innovationary bridge too far. It may well be that what we were lacking was that critical piece: to overcome the trust factor we needed the blockchain.

On that note, here's another minute of the talk I copied before I realised my task was done!

The blockchain, regardless of all the complicated stuff you've heard about it, is simply a database that works just like the network. A computer network is everywhere and nowhere, nobody really owns it, and everybody cooperates to make it work, all of the nodes participate in the process, and they make the entire thing efficient.

Blockchains are simply databases updated to work on the network. And those databases are ones with different properties than the databases made to run on tape. They're decentralised, you can't edit anything, you can't delete anything, the history is stored perfectly, if you want to make an update you just republish a new version of it, and to ensure the thing has appropriate accountability you use digital signatures.

It's not nearly as complicated as the tech guys in blockchainland will tell you. Yes it's as complicated as the inside of an SQL database. All of your companies run SQL databases, none of you really know how they work, it's going to be just like that with blockchains. Two years you'll forget the word blockchain, you'll just hear database, and it'll mean the same thing. Probably.

February 03, 2015

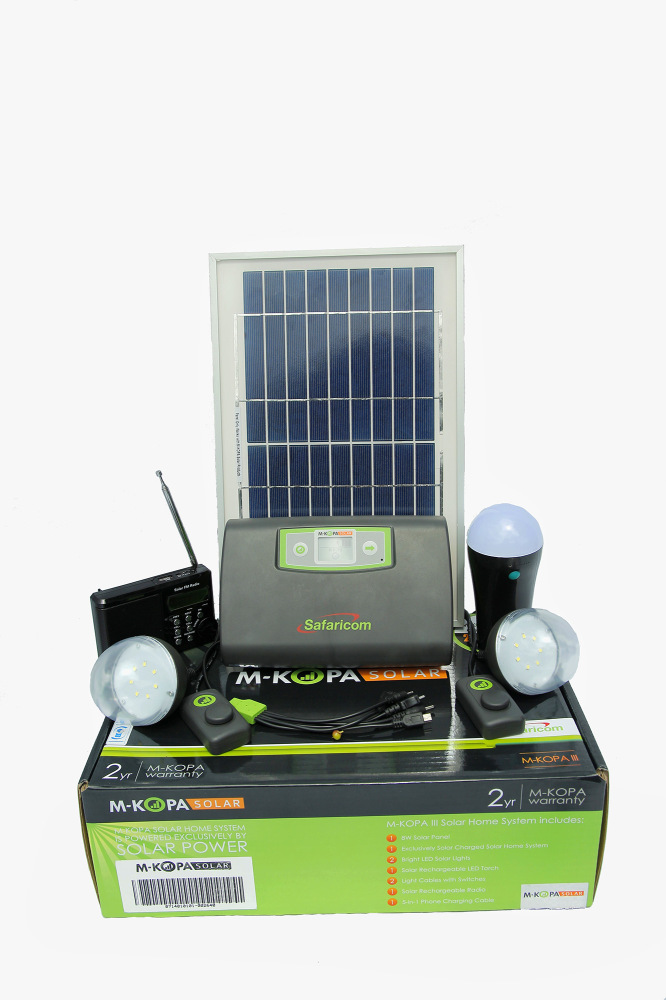

News that's news: Kenya's M-Kopa Solar Closes $12.45m

If there's any news worth blogging about, it is this:

If there's any news worth blogging about, it is this:

Breaking: Kenya's M-Kopa Solar Closes $12.45 million Fourth Funding Round

M-KOPA Solar has today closed its fourth round of investment through a $12.45 million equity and debt deal, led by LGT Venture Philanthropy. The investment will be used to expand the company's product range, grow its operating base in East Africa and license its technology to other markets.

Lead investor LGT Venture Philanthropy has backed M-KOPA since 2011 and is making its biggest investment yet in the fourth round, which also includes reinvestments from Lundin Foundation and Treehouse Investments (advised by Imprint Capital)and a new investment from Blue Haven Initiative.

In less than two and a half years since launch, M-KOPA Solar has installed over 150,000 residential solar systems in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, and is now connecting over 500 new homes each day. The company plans to further expand its distribution and introduce new products to reach an even larger customer base.

Jesse Moore, Managing Director and Co-Founder M-KOPA Solar says, "Our investors see innovation and scale in what M-KOPA does. And we see a massive unmet market opportunity to provide millions of off-gridhouseholds with affordable, renewable energy. We are just getting started in terms of the scale and impact of what we will achieve.

Oliver Karius, Partner, LGT Venture Philanthropy says, "We believe that we are at the dawn of a multi-billion dollar 'pay-as-you-go' energy industry. LGT Venture Philanthropy is a long-term investor in M-KOPA Solar because they've proven to be the market leaders,both in terms of innovating and delivering scale. We have also seen first-hand what positive impacts their products have on customers lives - making low-income households wealthier and healthier."

This deal follows the successful $20 million (KES1.8 billion) third round funding closed in December 2013 - which featured a working capital debt facility, led by the Commercial Bank of Africa.

The reason this is real news in the "new" sense is that indigenous solutions can work because they are tailored to the actual events and activities on the ground. In contrast, the western aid / poverty agenda typically doesn't work and does more harm than good, because it is an export of western models to countries that aren't aligned to those assumptions. Message to the west: Go away, we've got this ourselves.

January 20, 2015

Hitler v. modern western state of the art transit payment systems: Hitler 1, rich white boys 0.

As predicted in the first day we saw it (and published on this blog much later), mass transit payment systems are failing in Kenya:

Payment cards rolling back gains in Kenya's public transport sectorby Bedah Mengo NAIROBI (Xinhua) -- "Cash payment only", reads a sticker in a matatu plying the city center-Lavington route in Nairobi, Kenya. The vehicle belonging to a popular company was among the first to implement the cashless fare payment system that the Kenya government is rooting for.

And as it left the city center to the suburb on Monday, some passengers were ready to pay their fares using payment cards. However, the conductor announced that he would not accept cashless payments.

"Please pay in cash," he said. "We have stopped using the cashless system."When one of the passengers complained, the conductor retorted as he pointed at the sticker pasted on the wall of the minibus. "This is not my vehicle, I only follow orders."

All passengers paid their fares in cash as those who had payment cards complained of having wasted money on the gadgets. The experience in the vehicle displays the fate of the cashless fare payment in the East African nation. The system is fast-fading from the country's transport barely a month after the government made frantic efforts to entrench it. ...

It's probably too late for them now, but I think there are ways to put such a system out through Kenya's mass transit. You just don't do it that way because the market will not accept it. Rejection was totally obvious, and not only because asymmetric payment mechanisms don't succeed if both sides have a choice:

The experience in the vehicle displays the fate of the cashless fare payment in the East African nation. The system is fast-fading from the country's transport barely a month after the government made frantic efforts to entrench it.The Kenya government imposed a December 1, 2014 deadline as the time when all the vehicles in the nation should be using payment cards. A good number of matatu operators installed the system as banks and mobile phone companies launched cards to cash in on the fortune.

Commuters, on the other hand, bought the cards to avoid being inconvenienced. However, the little gains that were made in that period are eroding as matatu operators who had embraced the system go back to the cash.

"We were stopped from using the cashless system, because the management found it cumbersome. They said they were having cash-flow problems due to the bureaucracies involved in getting payments from the bank. None of our fleet now uses the system," explained the conductor.A spot on various routes in the city indicated that there are virtually no vehicles using the cashless system.

"When it failed to take off on December 1 last year, many vehicles that had installed the system abandoned it. They have the gadgets, but they are not using them," said Manuel Mogaka, a matatu operator on the Umoja route.

As I pointed out the root issue they missed here was the incentives of, well, just about everyone on the bus!

If someone is serious about this, I can help, but I take the real cash, not fantasy plastic. I spent some time working the real issues in Kenya, and they have more latent potential waiting to be tapped than just about any country on the planet. Our designs were good, but that's because they were based on helping people with problems they wanted solved and were willing to work to solve.

The ditching of the payment cards means that the Kenya government has a herculean task in implementing the system.

"It is not only us who are uncomfortable with the system, even passengers. Mid December last year, some passengers disembarked from my vehicle when I insisted I was only taking cashless fare. I had to accept cash because passengers were not boarding," said Mogaka.

Not handwavy bureaucratic agendas like "stamp out corruption." Yes, you! Read this on corruption and not this:

Kenya's Cabinet Secretary for Transport and Infrastructure Joseph Kamau said despite the challenges, the system will be implemented fully. He noted that the government will only renew licences of the vehicles that have installed the system.But matatu operators have faulted the directive, noting that it would be pointless to have the system when commuters do not have payment cards.

"Those cards can only work with people who have regular income and are able to budget a certain amount of money for fare every month. But if your income is irregular and low, it cannot work," said George Ogundi, casual laborer who stays in Kayole on the east of Nairobi.Analysts note that the rush in implementing the system has made Kenya's public transport sector a "graveyard" where the cashless payment will be buried.

"The government should have first started with revamping the sector by coming up with a well-organized metropolitan buses like those found in developed world. People would have seen their benefits and embraced cashless fare payment," said Bernard Mwaso of Edell IT Solutions in Nairobi.

(Obviously, if the matatu owners don't install, government resistance will last about a day after the deadline.)

December 21, 2014

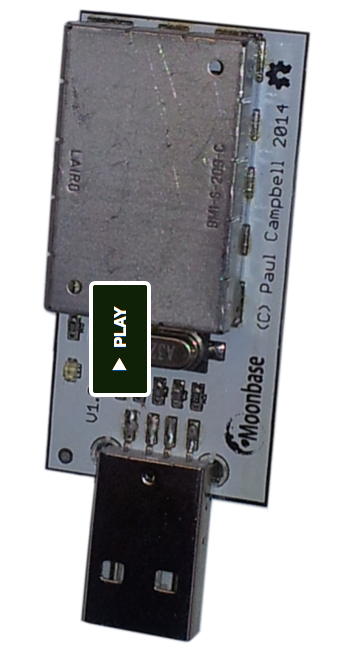

OneRNG -- open source design for your random numbers

Paul of Moonbase has put a plea onto kickstarter to fund a run of open RNGs. As we all know, having good random numbers is one of those devilishly tricky open problems in crypto. I'd encourage one and all to click and contribute.

Paul of Moonbase has put a plea onto kickstarter to fund a run of open RNGs. As we all know, having good random numbers is one of those devilishly tricky open problems in crypto. I'd encourage one and all to click and contribute.

For what it's worth, in my opinion, the issue of random numbers will remain devilish & perplexing until we seed hundreds of open designs across the universe and every hardware toy worth its salt also comes with its own open RNG, if only for the sheer embarrassment of not having done so before.

OneRNG is therefore massively welcome:

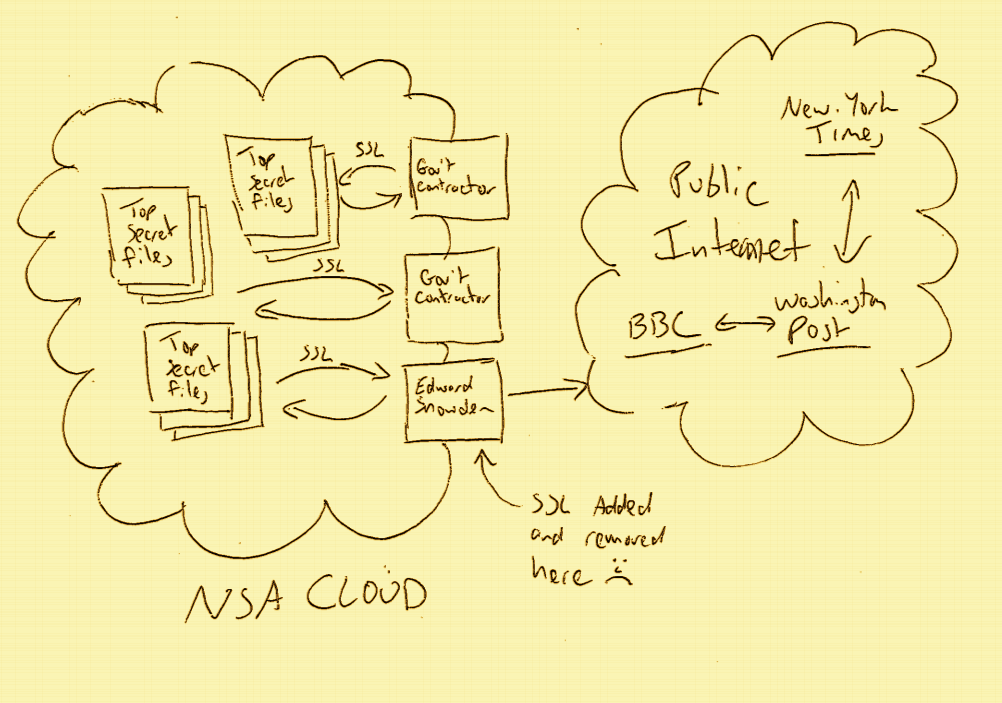

About this projectAfter Edward Snowden's recent revelations about how compromised our internet security has become some people have worried about whether the hardware we're using is compromised - is it? We honestly don't know, but like a lot of people we're worried about our privacy and security.

What we do know is that the NSA has corrupted some of the random number generators in the OpenSSL software we all use to access the internet, and has paid some large crypto vendors millions of dollars to make their software less secure. Some people say that they also intercept hardware during shipping to install spyware.

We believe it's time we took back ownership of the hardware we use day to day. This project is one small attempt to do that - OneRNG is an entropy generator, it makes long strings of random bits from two independent noise sources that can be used to seed your operating system's random number generator. This information is then used to create the secret keys you use when you access web sites, or use cryptography systems like SSH and PGP.

Openness is important, we're open sourcing our hardware design and our firmware, our board is even designed with a removable RF noise shield (a 'tin foil hat') so that you can check to make sure that the circuits that are inside are exactly the same as the circuits we build and sell. In order to make sure that our boards cannot be compromised during shipping we make sure that the internal firmware load is signed and cannot be spoofed.

OneRNG has already blasted through its ask of $10k. It's definitely still worth contributing more because it ensures a bigger run and helps much more attention on this project. As well, we signal to the world:

*we need good random numbers*

and we'll fight aka contribute to get them.

December 04, 2014

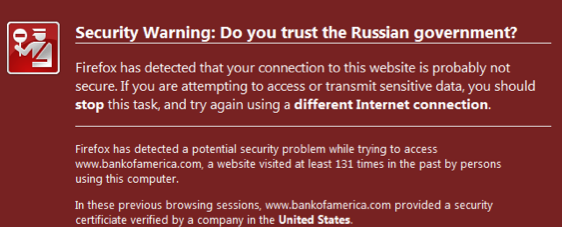

MITM watch - sitting in an English pub, get MITM'd

So, sitting in a pub idling till my 5pm, thought I'd do some quick check on my mail. Someone likes my post on yesterday's rare evidence of MITMs, posts a comment. Nice, I read all comments carefully to strip the spam, so, click click...

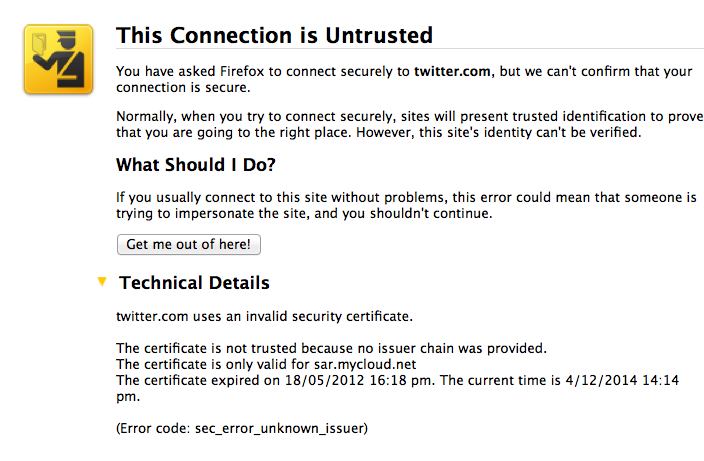

Boom, Firefox takes me through the wrestling trick known as MITM procedure. Once I've signalled my passivity to its immoral arrest of my innocent browsing down mainstreet, I'm staring at the charge sheet.

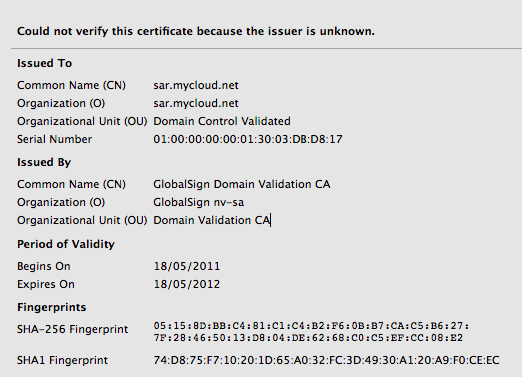

Whoops -- that's not financialcryptography.com's cert. I'm being MITM'd. For real!

Fully expecting an expiry or lost exception or etc, I'm shocked! I'm being MITM'd by the wireless here in the pub. Quick check on twitter.com who of course simply have to secure all the full tweetery against all enemies foreign and domestic and, same result. Tweets are being spied upon. The horror, the horror.

On reflection, the false positive result worked. One reason for that on the skeptical side is that, as I'm one of the 0.000001% of the planet that has wasted significant years on the business of protecting the planet against the MITM, otherwise known as the secure browsing model (queue in acronyms like CA, PKI, SSL here...), I know exactly what's going on.

How do I judge it all? I'm annoyed, disturbed, but still skeptical as to just how useful this system is. We always knew that it would pick up the false positive, that's how Mozilla designed their GUI -- overdoing their approach. As I intimated yesterday, the real problem is whether it works in the presence of a flood of false negatives -- claimed attacks that aren't really attacks, just normal errors and you should carry on.

Secondly, to ask: Why is a commercial process in a pub of all places taking the brazen step of MITMing innocent customers? My guess is that users don't care, don't notice, or their platforms are hiding the MITM from them. One assumes the pub knows why: the "free" service they are using is just raping their customers with a bit of secret datamining to sell and pillage.

Well, just another another data point in the war against the users' security.

December 03, 2014

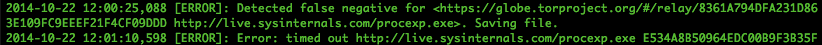

MITM watch - patching binaries at Tor exit nodes

The real MITMs are so rare that protocols that are designed around them fall to the Bayesian impossibility syndrome (*). In short, false negatives cause the system to be ignored, and when the real negative indicator turns up it is treated as a false. Ignored. Fail.

Here's some evidence of that with Tor:

... I tested BDFProxy against a number of binaries and update processes, including Microsoft Windows Automatic updates. The good news is that if an entity is actively patching Windows PE files for Windows Update, the update verification process detects it, and you will receive error code 0x80200053..... If you Google the error code, the official Microsoft response is troublesome.

If you follow the three steps from the official MS answer, two of those steps result in downloading and executing a MS 'Fixit' solution executable. ... If an adversary is currently patching binaries as you download them, these 'Fixit' executables will also be patched. Since the user, not the automatic update process, is initiating these downloads, these files are not automatically verified before execution as with Windows Update. In addition, these files need administrative privileges to execute, and they will execute the payload that was patched into the binary during download with those elevated privileges.

(*) I'd love to hear a better name than Bayesian impossibility syndrome, which I just made up. It's pretty important, it explains why the current SSL/PKI/CA MITM protection can never work, relying on Bayesian statistics to explain why infrequent real attacks cannot be defended against when overshadowed by frequent false negatives.

October 12, 2014

In the Shadow of Central Banking

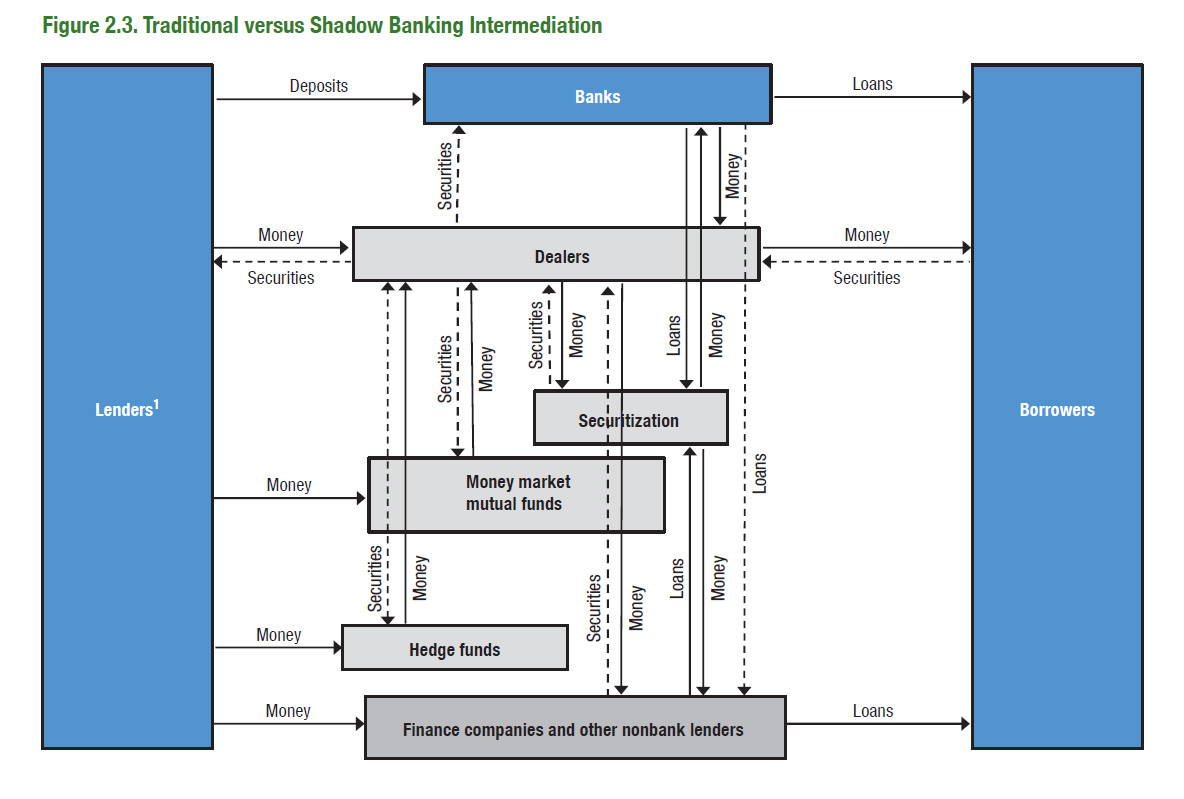

A recent IMF report on shadow banking places it at in excess of $70 trillion.

"Shadow banking can play a beneficial role as a complement to traditional banking by expanding access to credit or by supporting market liquidity, maturity transformation and risk sharing," the IMF said in the report. "It often, however, comes with bank-like risks, as seen during the 2007-08 global financial crisis."

It's a concern, say the bankers, it keeps the likes of Jamie Dimon up at night. But, what is it? What is this thing called shadow banking? For that, the IMF report has a nice graphic:

Aha! It's the new stuff: securitization, hedge funds, Chinese 'wealth management products' etc. So what we have here is a genie that is out of the bottle. As described at length, the invention of securitization allows a shift from banking to markets which is unstoppable.

In theoretical essence, markets are more efficient than middlemen, although you'd be hard pressed to call either the markets or banking 'efficient' from recent history.

Either way, this genie is laughing and dancing. The finance industry had its three wishes, and now we're paying the cost.

July 23, 2014

on trust, Trust, trusted, trustworthy and other words of power

Follows is the clearest exposition of the doublethink surrounding the word 'trust' that I've seen so far. This post by Jerry Leichter on Crypto list doesn't actually solve the definitional issue, but it does map out the minefield nicely. Trustworthy?

On Jul 20, 2014, at 1:16 PM, Miles Fidelman <...> wrote:

>> On 19/07/2014 20:26 pm, Dave Horsfall wrote:

>>>

>>> A trustworthy system is one that you *can* trust;

>>> a trusted system is one that you *have* to trust.

>>

> Well, if we change the words a little, the government

> world has always made the distinction between:

> - certification (tested), and,

> - accreditation (formally approved)

The words really are the problem. While "trustworthy" is pretty unambiguous, "trusted" is widely used to meant two different things: We've placed trust in it in the past (and continue to do so), for whatever reasons; or as a synonym for trustworthy. The ambiguity is present even in English, and grows from the inherent difficulty of knowing whether trust is properly placed: "He's a trusted friend" (i.e., he's trustworthy); "I was devastated when my trusted friend cheated me" (I guess he was never trustworthy to begin with).

In security lingo, we use "trusted system" as a noun phrase - one that was unlikely to arise in earlier discourse - with the *meaning* that the system is trustworthy.

Bruce Schneier has quoted a definition from some contact in the spook world: A trusted system (or, presumably, person) is one that can break your security. What's interesting about this definition is that it's like an operational definition in physics: It completely removes elements about belief and certification and motivation and focuses solely on capability. This is an essential aspect that we don't usually capture.

When normal English words fail to capture technical distinctions adequately, the typical response is to develop a technical vocabulary that *does* capture the distinctions. Sometimes the technical vocabulary simply re-purposes common existing English words; sometimes it either makes up its own words, or uses obscure real words - or perhaps words from a different language. The former leads to no end of problems for those who are not in the field - consider "work" or "energy" in physics. The latter causes those not in the field to believe those in it are being deliberately obscurantist. But for those actually in the field, once consensus is reached, either approach works fine.

The security field is one where precise definitions are *essential*. Often, the hardest part in developing some particular secure property is pinning down precisely what the property *is*! We haven't done that for the notions surrounding "trust", where, to summarize, we have at least three:

1. A property of a sub-system a containing system assumes as part of its design process ("trusted");

2. A property the sub-system *actually provides* ("trustworthy").

3. A property of a sub-system which, if not attained, causes actual security problems in the containing system (spook definition of "trusted").

As far as I can see, none of these imply any of the others. The distinction between 1 and 3 roughly parallels a distinction in software engineering between problems in the way code is written, and problems that can actually cause externally visible failures. BTW, the software engineering community hasn't quite settled on distinct technical words for these either - bugs versus faults versus errors versus latent faults versus whatever. To this day, careful papers will define these terms up front, since everyone uses them differently.

June 20, 2014

Signalling and MayDay PAC

There's a fascinating signalling opportunity going on with US politics. As we all know, 99% the USA congress seats are paid for by contributions from corporate funders, through a mechanism called PACs or political action committees. Typically, the well-funded campaigns win the seats, and for that you need a big fat PAC with powerful corporate wallets behind.

Lawrence Lessig decided to do something about it.

"Yes, we want to spend big money to end the influence of big money... Ironic, I get it. But embrace the irony."

So, fighting fire with fire, he started the Mayday PAC:

"We’ve structured this as a series of matched-contingent goals. We’ve got to raise $1 million in 30 days; if we do, we’ll get that $1 million matched. Then we’ve got to raise $5 million in 30 days; if we do, we’ll get that $5 million matched as well. If both challenges are successful, then we’ll have the money we need to compete in 5 races in 2014. Based on those results, we’ll launch a (much much) bigger effort in 2016 — big enough to win."

They got to their first target, the 2nd of $5m will close in 30th June. Larry claims to have been inspired by Aaron Swartz:

“How are you ever going to address those problems so long as there’s this fundamental corruption in the way our government works?” Swartz had asked.

Something much at the core of the work I do in Africa.

The signalling opportunity is the ability to influence total PAC spending by claiming to balance it out. If MayDay PAC states something simple such as "we will outspend the biggest spend in USA congress today," then how do the backers for the #1 financed-candidate respond to the signal?

As the backers know that their money will be balanced out, it will no longer be efficacious to buy their decisions *with the #1 candidate*. They'll go elsewhere with their money, because to back their big man means to also attract the MayDay PAC.

Which will then leave the #2 paid seat in Congress at risk ... who will also commensurately lose funds. And so on ... A knock-on effect could rip the funding rug from many top campaigns, leveraging Lessig's measly $12m way beyond its apparent power.

A fascinating experiment.

The challenge of capturing people’s attention isn’t lost on Lessig. When asked if anyone has told him that his idea is ludicrous and unlikely to work, he answers with a smile: “Yeah, like everybody.”

Sorry, not this anybody. This will work. Economically speaking, signalling does work. Go Larry!

May 07, 2014

A triple-entry explanation for a minimum viable Blockchain

It's an article of faith that accounting is at the core of cryptocurrencies. Here's a nice story along those lines h/t to Graeme:

Ilya Grigorik provides a ground-up technologists' description of Bitcoin called "The Minimum Viable Blockchain." He starts at bartering, goes through triple-entry and the replacement of the intermediary with the blockchain, and then on to explain how all the perverse features strengthen the blockchain. It's interesting to see how others see the nexus between triple-entry and bitcoin, and I think it is going to be one of future historian's puzzles to figure out how it all relates.

Both Bob and Alice have known each other for a while, but to ensure that both live up to their promise (well, mostly Alice), they agree to get their transaction "notarized" by their friend Chuck.They make three copies (one for each party) of the above transaction receipt indicating that Bob gave Alice a "Red stamp". Both Bob and Alice can use their receipts to keep account of their trade(s), and Chuck stores his copy as evidence of the transaction. Simple setup but also one with a number of great properties:

- Chuck can authenticate both Alice and Bob to ensure that a malicious party is not attempting to fake a transaction without their knowledge.

- The presence of the receipt in Chuck's books is proof of the transaction. If Alice claims the transaction never took place then Bob can go to Chuck and ask for his receipt to disprove Alice's claim.

- The absence of the receipt in Chuck's books is proof that the transaction never took place. Neither Alice nor Bob can fake a transaction. They may be able to fake their copy of the receipt and claim that the other party is lying, but once again, they can go to Chuck and check his books.

- Neither Alice nor Bob can tamper with an existing transaction. If either of them does, they can go to Chuck and verify their copies against the one stored in his books.

What we have above is an implementation of "triple-entry bookkeeping", which is simple to implement and offers good protection for both participants. Except, of course you've already spotted the weakness, right? We've placed a lot of trust in an intermediary. If Chuck decides to collude with either party, then the entire system falls apart.

Grigorik then uses public key cryptography to ensure that the receipt becomes evidence that is reliable for all parties; which is how I built it, and I'm pretty sure that was what was intended by Todd Boyle.

However he walks a different path and uses the signed receipts as a way to drop the intermediary and have Alice and Bob keep separate, independent ledgers. I'd say this is more a means to an end, as Grigorik is trying to explain Bitcoin, and the central tenant of that cryptocurrency was the famous elimination of a centralised intermediary.

Moral of the story? Be (very) careful about your choice of the intermediary!

I don't have time right now to get into the rest of the article, but so far it does seem like a very good engineer's description. Well worth a read to sort your head out when it comes to all the 'extra' bits in the blockchain form of cryptocurrencies.

April 18, 2014

Shots over the bow -- Haiti joins with USA to open up payments for the people

The separation of payments from banks is accelerating. News from Haiti:

The past year in Haiti has been marked by the slow pace of the earthquake recovery. But the poorest nation in the hemisphere is moving quickly on something else - setting up "mobile money" networks to allow cell phones to serve as debit cards.The systems have the potential to allow Haitians to receive remittances from abroad, send cash to relatives across town or across the country, buy groceries and even pay for a bus ride all with a few taps of their cell phones.

Using phones to handle money payments is something we know works. It works so well that some 35% of the economy in Kenya moves this way (I forget the numbers). It works so well Kenya doesn't care about the banks freezing up the economy any more because they have an alternate system, they have resiliance in payments. It works so well that everyone can do mPesa, even the unbanked, which is most of them, bank accounts costing the same in Kenya as the west.

It works so well that mPesa has been the biggest driver to new bank accounts...

Yet mPesa hasn't been followed around the world. The reason is pretty simple -- regulatory interference. Central banks, I'm looking at you. In Kenya, the mission of "financial inclusion" won the day; in other countries around the world, central banks worked against wealth for the poorest by denying them payments on the mobile.

Is it that drastic? Yes. Were the central banks well-minded? Sure, they thought they were doing the right thing, but they were wrong. Mobile money equals wealth for the poor and there is no way around that fact. Stopping mobile money means taking money from the poor, in the big picture. Everything else is noise.

So when the poorest of the poor -- the Haitian earthquake victims were left in the mud, there were no banks left to serve them (sell them?) and the only way to get value out there turned out to be using the mobile phone.

That included, giving the users free mobile phones.

Can you see an important value point here? The value to society of getting mobile money to the poor is in excess of the price of the mobile phone.

Well, this only happens in poor countries, right? Wrong again. The financial costs that are placed on the poor of every country by the decisions of the central banks are common across all countries. Now comes Walmart, for that very express same reason:

In a move that threatens to upend another piece of the financial services industry, Walmart, the country’s largest retailer, announced on Thursday that it would allow customers to make store-to-store money transfers within the United States at cut-rate fees.This latest offer, aimed largely at lower-income shoppers who often rely on places like check-cashing stores for simple transactions, represents another effort by the giant retailer to carve out a space in territory that once belonged exclusively to traditional banks.

...

Lower-income consumers have been a core demographic for Walmart, but in recent quarters those shoppers have turned increasingly to dollar stores.

...

More than 29 percent of households in the United States did not have a savings account in 2011, and about 10 percent of households did not have a checking account, according to a study sponsored by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. And while alternative financial products give consumers access to services they might otherwise be denied, people who are shut out of the traditional banking system sometimes find themselves paying high fees for transactions as basic as cashing a check.

See the common thread with Bitcoin? Message to central banks: shut the people out, and they will eventually respond. The tide is now turning, and banks and central banks no longer have the credibility they once had to stomp on the poor. The question for the future is, which central banks will break ranks first, and align themselves with their countries and their peoples?

February 09, 2014

Digital Evidence journal is now open source!

Stephen Mason, the world's foremost expert on the topic, writes (edited for style):

Stephen Mason, the world's foremost expert on the topic, writes (edited for style):

The entire Digital Evidence and Electronic Signature Law Review is now available as open source for free here:Current Issue Archives All of the articles are also available via university library electronic subscription services which require accounts:

EBSCO Host HeinOnline v|lex (has abstracts) If you know of anybody that might have the knowledge to consider submitting an article to the journal, please feel free to let them know of the journal.

This is significant news for the professional financial cryptographer! For those who are interested in what all this means, this is the real stuff. Let me explain.

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a little thing called the electronic signature, and its RSA cousin, the digital signature. Businesses, politicians, spooks and suppliers dreamed that they could inspire a world-wide culture of digitally signing your everything with a hand wave, with the added joy of non-repudiation.

They failed, and we thank our lucky stars for it. People do not want to sign away their life every time some little plastic card gets too close to a scammer, and thankfully humanity had the good sense to reject the massively complicated infrastructure that was built to enslave them.

However, a suitably huge legacy of that folly was the legislation around the world to regulate the use of electronic signatures -- something that Stephen Mason has catalogued here.

In contrast to the nuisance level of electronic signatures, in parallel, a separate development transpired which is far more significant. This was the increasing use of digital techniques to create trails of activity, which led to the rise of digital evidence, and its eventual domination in legal affairs.

Digital discovery is now the main act, and the implications have been huge if little understated outside legal circles, perhaps because of the persistent myth in technology circles that without digital signatures, evidence was worth less.

Every financial cryptographer needs to understand the implications of digital evidence, because without this wisdom, your designs are likely crap. They will fail when faced with real-world trials, in both senses of the word.

I can't write the short primer on digital evidence for you -- I'm not the world's expert, Stephen is! -- but I can /now/ point you to where to read.That's just one huge issue, hitherto locked away behind a hugely dominating paywall. Browse away at all 10 issues!

November 10, 2013

The NSA will shape the worldwide commercial cryptography market to make it more tractable to...

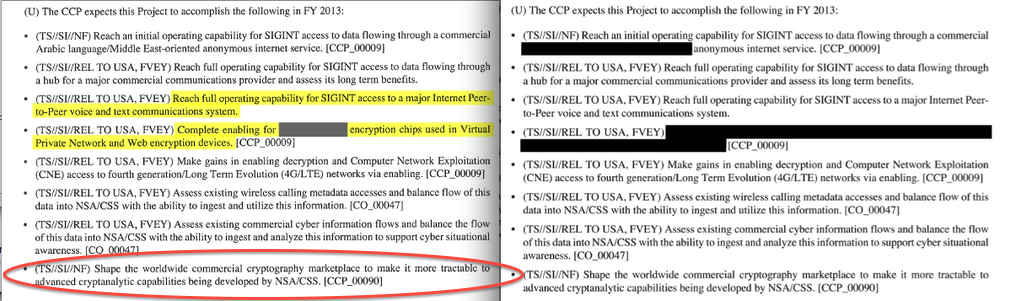

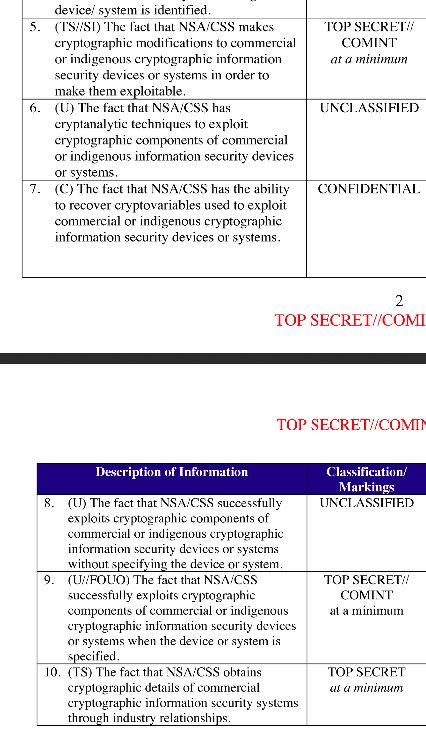

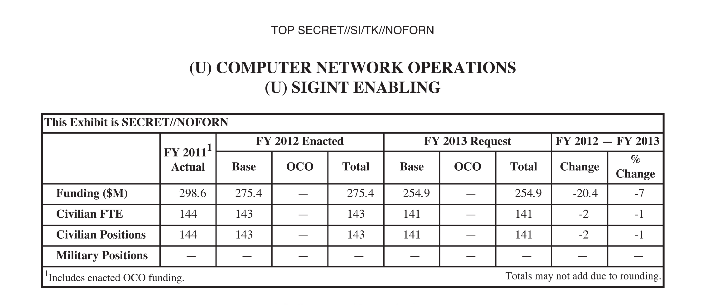

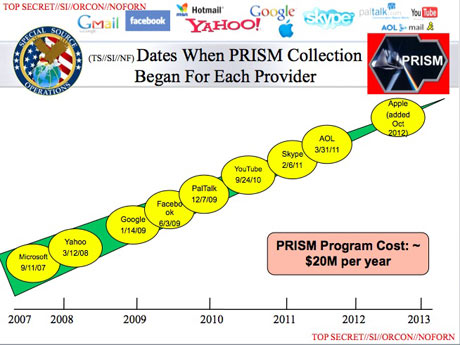

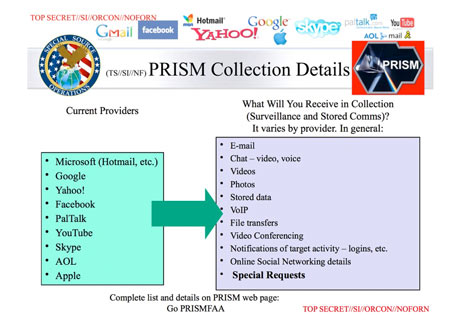

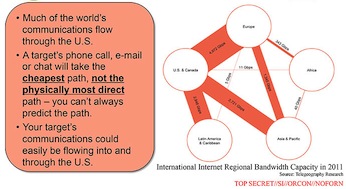

In the long running saga of the Snowden revelations, another fact is confirmed by ashkan soltani. It's the last point on this slide showing some nice redaction minimisation.

In words:

(U) The CCP expects this Project to accomplish the following in FY 2013:

Confirmed: the NSA manipulates the commercial providers of cryptography to make it easier to crack their product. When I said, avoid American-influenced cryptography, I wasn't joking: the Consolidated Cryptologic Program (CCP) is consolidating access to your crypto.

Addition: John Young forwarded me the original documents (Guardian and NYT) and their blanket introduction makes it entirely clear:

(TS//SI//NF) The SIGINT Enabling Project actively engages the US and foreign IT industries to covertly influence and/or overtly leverage their commercial products' designs. These design changes make the systems in question exploitable through SIGINT collection (e.g., Endpoint, MidPoint, etc.) with foreknowledge of the modification. ....

Note also that the classification for the goal above differs in that it is NF -- No Foreigners -- whereas most of the other goals listed are REL TO USA, FVEY which means the goals can be shared with the Five Eyes Intelligence Community (USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand).

Note also that the classification for the goal above differs in that it is NF -- No Foreigners -- whereas most of the other goals listed are REL TO USA, FVEY which means the goals can be shared with the Five Eyes Intelligence Community (USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand).

The more secret it is, the more clearly important is this goal. The only other goal with this level of secrecy was the one suggesting an actual target of sensitivity -- fair enough. More confirmation:

(U) Base resources in this project are used to:

- (TS//SI//REL TO USA, FVEY) Insert vulnerabilities into commercial encryption systems, IT systems, networks and endpoint communications devices used by targets.

- ...

and in goals 4, 5:

- (TS//SI//REL TO USA, FVEY) Complete enabling for [XXXXXX] encryption chips used in Virtual Private Network and Web encryption devices. [CCP_00009].