January 11, 2019

Gresham's Law thesis is back - Malware bid to oust honest miners in Monero

7 years after we called the cancer that is criminal activity in Bitcoin-like cryptocurrencies, here comes a report that suggests that 4.3% of Monero mining is siphoned off by criminals.

A First Look at the Crypto-Mining Malware

Ecosystem: A Decade of Unrestricted Wealth

Sergio Pastrana

Universidad Carlos III de Madrid*

spastran@inf.uc3m.esGuillermo Suarez-Tangil

King’s College London

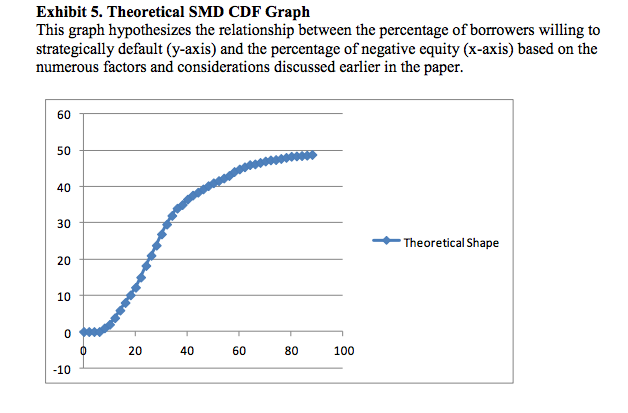

guillermo.suarez-tangil@kcl.ac.ukAbstract—Illicit crypto-mining leverages resources stolen from victims to mine cryptocurrencies on behalf of criminals. While recent works have analyzed one side of this threat, i.e.: web-browser cryptojacking, only white papers and commercial reports have partially covered binary-based crypto-mining malware. In this paper, we conduct the largest measurement of crypto-mining malware to date, analyzing approximately 4.4 million malware samples (1 million malicious miners), over a period of twelve years from 2007 to 2018. Our analysis pipeline applies both static and dynamic analysis to extract information from the samples, such as wallet identifiers and mining pools. Together with OSINT data, this information is used to group samples into campaigns.We then analyze publicly-available payments sent to the wallets from mining-pools as a reward for mining, and estimate profits for the different campaigns.Our profit analysis reveals campaigns with multimillion earnings, associating over 4.3% of Monero with illicit mining. We analyze the infrastructure related with the different campaigns,showing that a high proportion of this ecosystem is supported by underground economies such as Pay-Per-Install services. We also uncover novel techniques that allow criminals to run successful campaigns.

This is not the first time we've seen confirmation of the basic thesis in the paper Bitcoin & Gresham's Law - the economic inevitability of Collapse. Anecdotal accounts suggest that in the period of late 2011 and into 2012 there was a lot of criminal mining.

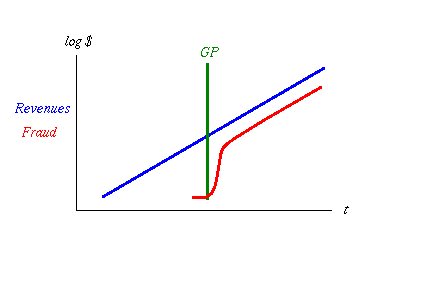

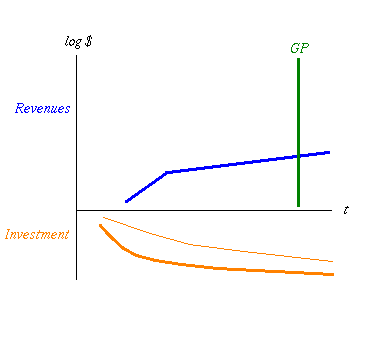

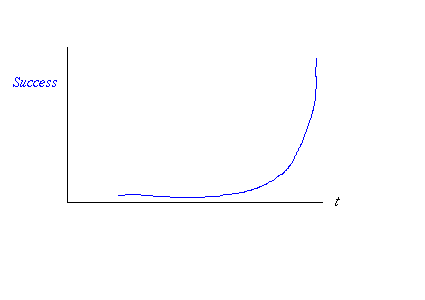

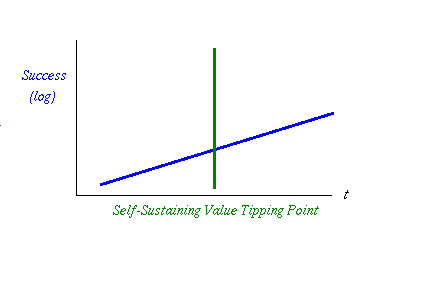

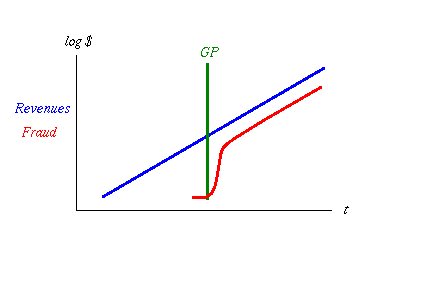

Our thesis was that criminal mining begets more, and eventually pushes out the honest business, of all form from mining to trade.

Testing the model: Mining is owned by BotnetsLet us examine the various points along an axis from honest to stolen mining: 0% botnet mining to 100% saturation. Firstly, at 0% of botnet penetration, the market operates as described above, profitably and honestly. Everyone is happy.

But at 0%, there exists an opportunity for near-free money. Following this opportunity, one operator enters the market by turning his botnet to mining. Let us assume that the operator is a smart and careful crook, and therefore sets his mining limit at some non-damaging minimum value such as 1% of total mining opportunity. At this trivial level of penetration, the botnet operator makes money safely and happily, and the rest of the Bitcoin economy will likely not notice.

However we can also predict with confidence that the market for botnets is competitive. As there is free entry in mining, an effective cartel of botnets is unlikely. Hence, another operator can and will enter the market. If a penetration level of 1% is non-damaging, 2% is only slightly less so, and probably nearly as profitable for the both of them as for one alone.

And, this remains the case for the third botnet, the fourth and more, because entry into the mining business is free, and there is no effective limit on dishonesty. Indeed, botnets are increasingly based on standard off-the-shelf software, so what is available to one operator is likely visible and available to them all.

What stopped it from happening in 2012 and onwards? Consensus is that ASICs killed the botnets. Because serious mining firms moved to using large custom rigs of ASICS, and as these were so much more powerful than any home computer, they effectively knocked the criminal botnets out of the market. Which the new paper acknowledged:

... due to the proliferation of ASIC mining, which uses dedicated hardware, mining Bitcoin with desktop computers is no longer profitable, and thus criminals’ attention has shifted to other cryptocurrencies.

Why is botnet mining back with Monero? Presumably because Monero uses an ASIC-resistant algorithm that is best served by GPUs. And is also a heavy privacy coin, which works nicely for honest people with privacy problems but also works well to hide criminal gains.

October 21, 2018

ID Dox - now it's getting personal - Andreas spoofed

Writes Andreas Antonopolous, a noted Bitcoin commentator, that he has been impersonated with a mere scan!

Writes Andreas Antonopolous, a noted Bitcoin commentator, that he has been impersonated with a mere scan!

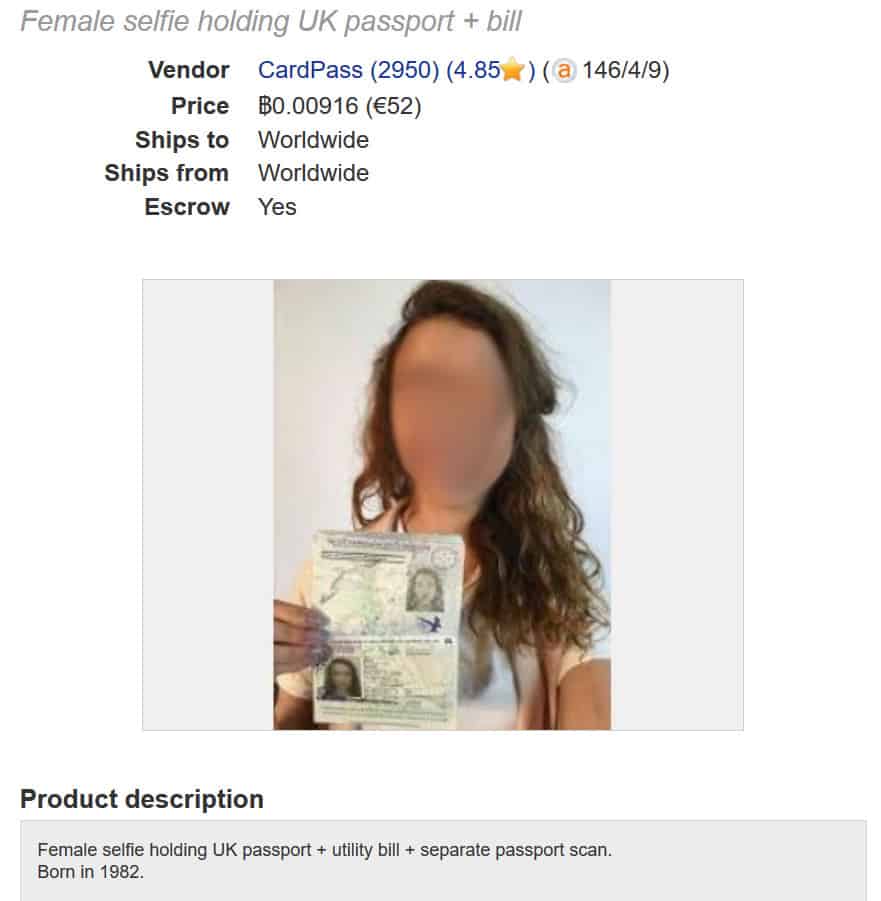

More than anything else this points at the fallacy of Identity Documents as the God of our Identity. AA may very well be a victim of our penultimate post on cheap-as-chips scans of your identity.

What's becoming clear is that identity is garnering more attention. Unwittingly, orgs and peoples who thought they had this under control are being dragged into the quagmire caused by firstly the Internet, then the upheavals caused by the great financial crisis and the drugs wars, and finally the devil of all devils, blockchain. Where will it end?

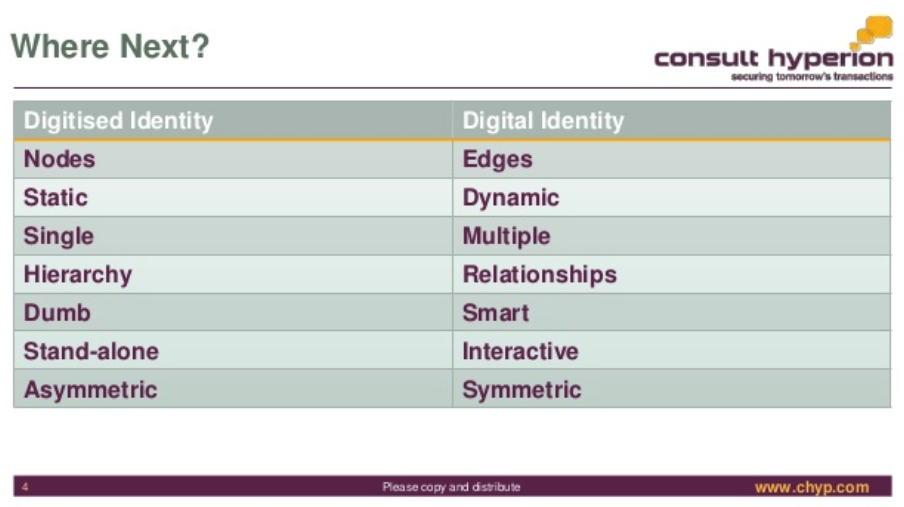

Meanwhile, here comes The Award-Winning David G.W. Birch @dgwbirch another understated twitter persona with slides and solutions for your identity:

The Award-Winning David G.W. Birch @dgwbirch A Short, Strategic Comment on Digital Identity by @chyppings #authentication #authorisation slideshare.net/15Mb/a-short-s… <- A short keynote for the Biometrics Congress in London. People liked it and asked for a copy so I've uploaded it to SlideShare.

I post this for debate not for endorsement ;-)

I'd also like to point out that it is unfortunate that <blockchain> is not a HTML entity, because that's what gets typed these days.

October 19, 2018

AES was worth $250 billion dollars

So says NIST...

10 years ago I annoyed the entire crypto-supply industry:

Hypothesis #1 -- The One True Cipher Suite In cryptoplumbing, the gravest choices are apparently on the nature of the cipher suite. To include latest fad algo or not? Instead, I offer you a simple solution. Don't.

There is one cipher suite, and it is numbered Number 1.

Cypersuite #1 is always negotiated as Number 1 in the very first message. It is your choice, your ultimate choice, and your destiny. Pick well.

The One True Cipher Suite was born of watching projects and groups wallow in the mire of complexity, as doubt caused teams to add multiple algorithms- a complexity that easily doubled the cost of the protocol with consequent knock-on effects & costs & divorces & breaches & wars.

It - The One True Cipher Suite as an aphorism - was widely ridiculed in crypto and standards circles. Developers and standards groups like the IETF just could not let go of crypto agility, the term that was born to champion the alternate. This sacred cow led the TLS group to field something like 200 standard suites in SSL and radically reduce them to 30 or 40 over time.

Now, NIST has announced that AES as a single standard algorithm is worth $250 billion economic benefit over 20 years of its project lifetime - from 1998 to now.

h/t to Bruce Schneier, who also said:

"I have no idea how to even begin to assess the quality of the study and its conclusions -- it's all in the 150-page report, though -- but I do like the pretty block diagram of AES on the report's cover."

One good suite based on AES allows agility within the protocol to be dropped. Entirely. Instead, upgrade the entire protocol to an entirely new suite, every 7 years. I said, if anyone was asking. No good algorithm lasts less than 7 years.

Crypto-agility was a sacred cow that should have been slaughtered years ago, but maybe it took this report from NIST to lay it down: $250 billion of benefit.

In another footnote, we of the Cryptix team supported the AES project because we knew it was the way forward. Raif built the Java test suite and others in our team wrote and deployed contender algorithms.

July 25, 2018

Zooko buys Groceries...

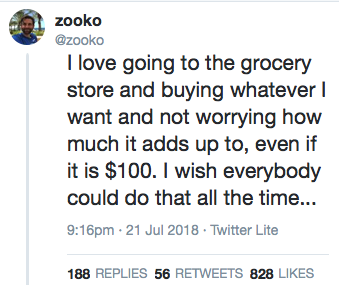

Zooko's tweet got me thinking, and it wasn't the flood of rejection he received.

I have been in that state, and I knew exactly what he meant. Been there, done that experience where you have to add each item, you have to shop for value, drop the things you want, and live on rice & beans.

I have been in that state, and I knew exactly what he meant. Been there, done that experience where you have to add each item, you have to shop for value, drop the things you want, and live on rice & beans.

Like billions of people.

Let me share an anecdote. Once upon a time I lived in Amsterdam. We had a sort of student or groupie house with some of us on the ground floor apartment and some of us on the next floor up. It was one of those places where the crazy landlady wanted crazy non-locals because we paid in cash and didn’t cause trouble.

My startup had just failed - in 1998 nobody wanted to issue hard cryptographically-protected secure instruments that could describe any money at all. Go figure. But those weren’t my worries then, what I was worried about then was … money.

Of the sort that purchased groceries, not the sort that the cypherpunks dreamed of and had but didn’t have. I would take the money to the grocery store and buy stuff. It was my job to do chilli con carne once in a while, like every few weeks. The money was someone else’s. Therefore my actual job was like taking a little money to the grocery store, buying 6 cans of tomatoes, 3 cans of beans, 1kg of minced meat, 3 chillies, onions and a lot of rice. Then cooking it and serving it.

That could feed about 5 adults for about 4 days.

That could feed about 5 adults for about 4 days.

For about 6 months I was in this state of poverty. It wasn’t the first time, nor the last, nor the worst - but it meant several things. I really had to watch the money. And wash clothes and iron shirts and cook chilli con carne and feed the group. I couldn’t make decisions because I couldn’t afford to make decisions. I couldn’t vary the menu because that was the cheapest.

Until I picked up a contract doing "requirements" for a local smart card money firm, I was stuck in this state. Every week or two, one of the guys from upstairs would invite me to the Bagel's 'n Beans (I think it was called) at the corner and we'd do breakfast in the sunshine and talk about financial cryptography and how to issue eCash and how to save the planet. Then he’d pay, and he’d go off to work because his startup hadn’t collapsed yet, and he still had a paycheck.

I was very conscious of the fact that if I hadn't had good friends, I'd be screwed. I was basically living for free while they were working their day jobs. It's hard to explain to those who have never faced it but there is a special hell for those who've had good paying jobs and then they get shut out. Of course, this happens to millions or billions, I'm not special.

The guy who liked Bagels was @zooko. Ever since that period I've tried to invite my poorer friends. Money didn’t matter, except when it did. Money was for living, not for making. Money was for doing, not for counting.

And I have thought a lot about what that time meant to me. It was that experience, and later experiences that led me to understand that the fabric of society isn't commerce, it isn't capitalism, it isn't profit and it very much isn't the dollar or the euro or the yen. The fabric of society is relationships. I didn't know it then, but I slowly found myself in the search for community. Not because I needed it, or not only, but because I thought that in community was the answer.

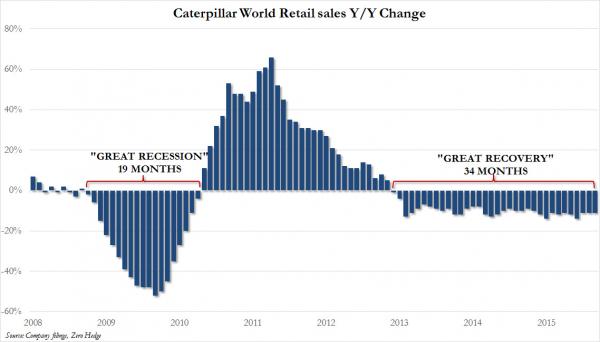

To the problem, and in 2008 I found myself again in deep poverty in the rich country of Austria. This time I had a job doing community auditing, which worked out at about €1 per hour, comfortably well below the poverty line, but alive. But, while we were building that community, we were watching the world’s financial community get into gridlock. Banks failing, countries on the verge, etc.

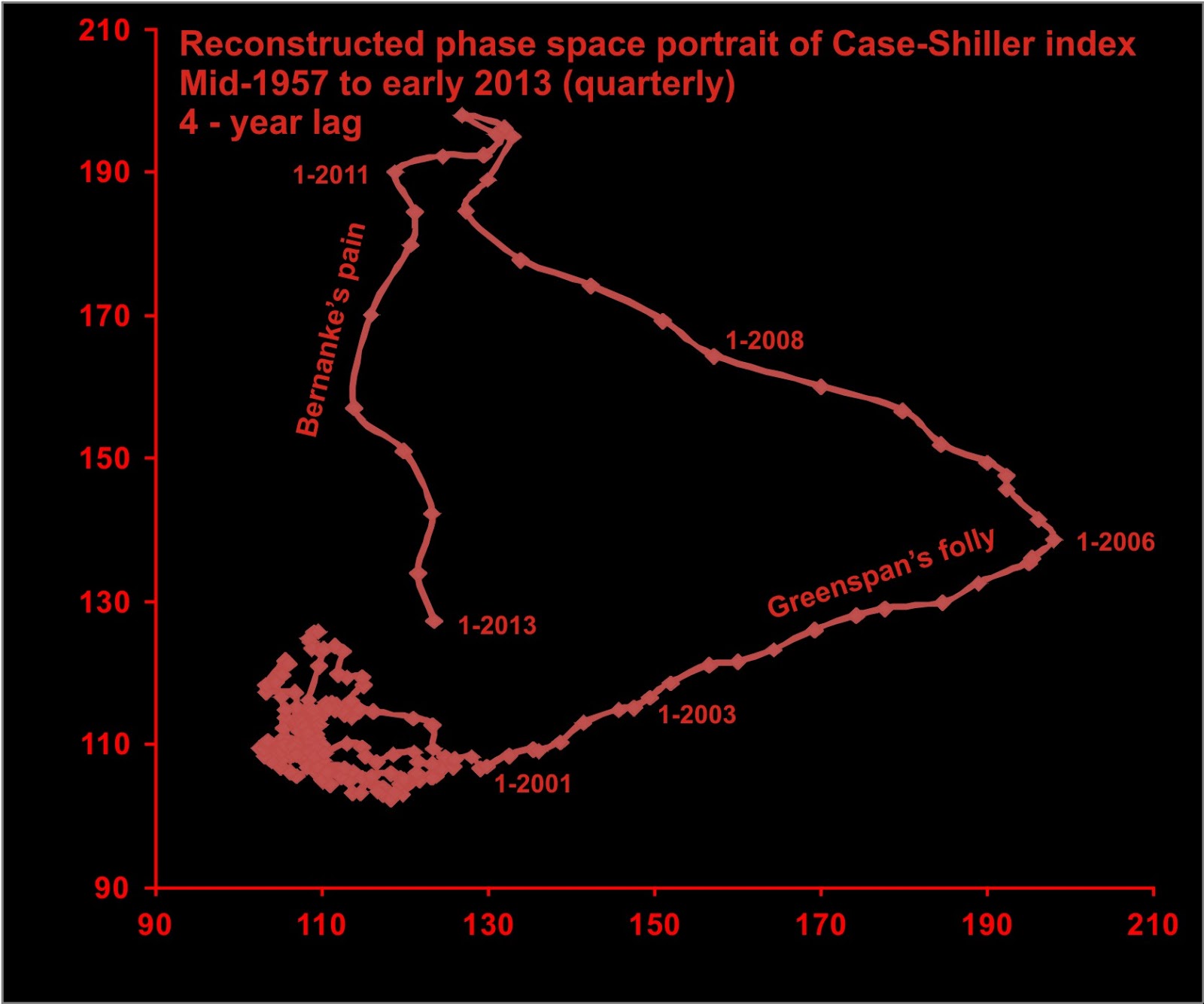

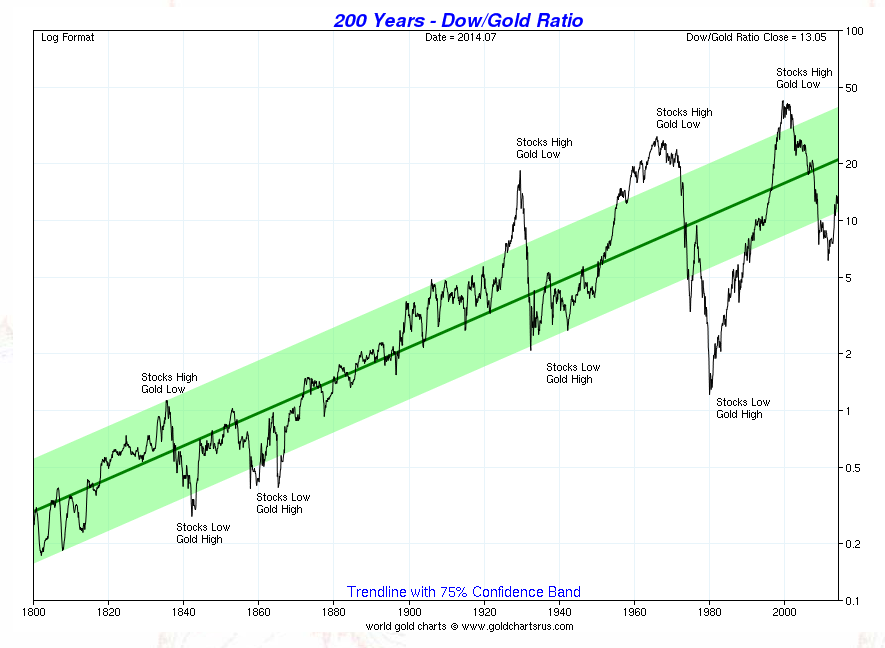

Since around 2000 - the dotcom crash - a lot of us had expected a real hard recession. It never happened, and we were mystified. Then in 2008 the answer was revealed. The man they called the magician, Alan Greenspan, had led bailout after bailout. Not of banks, but of the entire world system: the dotcom crash, 9/11, mutual funds scandal, fannie mae, something else... had all been rewarded with monstrous injections in liquidity. The banks or Alan Greenspan or someone had turned the entire western financial system into a bubble or a Ponzi or something.

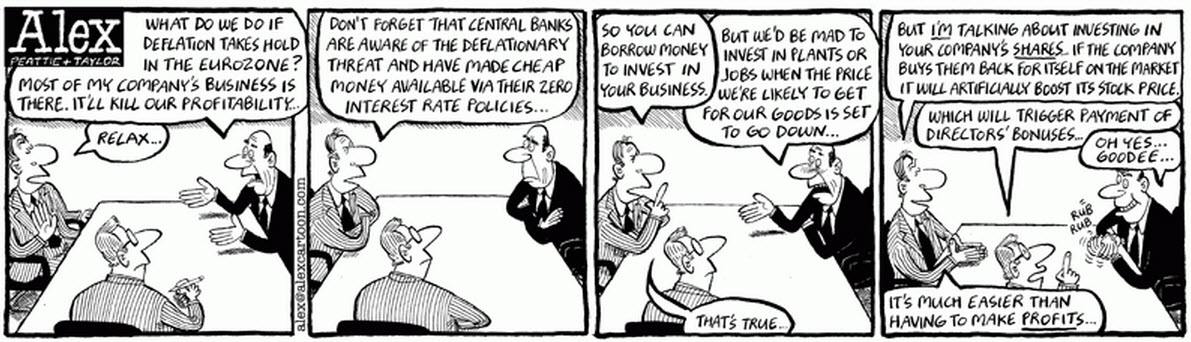

And this last decade has been the mother of all bailouts - Quantitative Easing is nothing more than a gift to the financial system.

The problem I'm looking at then takes on a new aspect. What happens when the mother of all bubbles pops? When, not only can we not afford the groceries, but when there aren’t any grocery stores? We know something of this from Greece, from Puerto Rico, from Venezuela. How is it that people survive?

I knew it was relationship but I didn't know how. I knew people would save people, but how? My experiences in Amsterdam and Vienna and a few other episodes gave me no clear pattern - I knew that people saved people, but who, when and why in each circumstance?

Until, after a few more years skidding along the planetary row I found the how in Kenya - the chamas. It wasn’t that Kenyans were smarter than the westerners (they can be, and they’re definitely smarter than NGOs and aid workers who come to help) but it was clearer that there were two environmental factors that led them to work smarter, better, safer: poverty and corruption. It was out of these twin forces - I theorise - that they augmented their family and local trust lines into chamas.

Finding the how was pretty exciting. It was the lightbulb moment - the Eureka thing. Enough for me to quit my really safe and boring job in Australia and go to Kenya to build the first generation of chamapesa. It wasn’t because our technology spoke to chamas and chamas listened. It wasn’t because I loved Africa and the people were wonderful, it wasn’t because the business plan gasped an exponential curve to the moon. And it wasn’t because we could put a billion Africans on the blockchain, or a million blockchains on Africans.

It was because here was the solution, to everything I had not been able to work out before.

Like Zooko and a billion other people I’d spent many years in the grocery accounting trap. Like Zooko and millions of other people I’d lived the life of intelligent comfortable wealth and didn’t really care how much things cost.

Like Zooko and a billion other people I’d spent many years in the grocery accounting trap. Like Zooko and millions of other people I’d lived the life of intelligent comfortable wealth and didn’t really care how much things cost.

But like Zooko and a much smaller group of people, I've lived both those lives. That shock of poverty was burnt into our rich, educated privileged brains. And it matters. It drives us. It owns us, it changes us. I went to Kenya not for them but for all of us. To be nauseous, Chamapesa is our plan to get everyone to the grocery store so they don't care about the cost. And it is the rich west as well as the entrepreneurial Africans who'll need this.

So when Zooko posts on his experiences, and gets attacked for lack of humility or lack of gratefulness, I understand the angst that these people have, but honestly, they’ve missed the point. Having lived on both sides of the tracks, it isn’t gratefulness or humility or charity that we find or care for or should exhibit, it is clarity of thought.

And this is where we separate from those in Silicon Valley or the NGO armies or the twitter social justice warriors or regulators or other oligopolists. They’ll never understand because those people have only lived on one side of the tracks.

You can't "fight poverty" when you work for a family wealth fund. You can't "save the poor" when you live in Silicon Valley and whiteboards & google are the extent of your knowledge. You can't blockchain your way to understanding. You can't "bank the unbanked" when your entire worldview is driven by the World Bank. You can't "give charitably" and expect that money to be spent wisely by those who receive charitably.

You get your degree in poverty by living it, not by going to University and studying IMF reports. So when Zooko exhibits his particular penchant for unfiltered thought, it is not going to fit in with people's polite ways of ignoring problems - humility, gratefulness, charity are all comforting techniques to avoid the problem.

The problem that Zooko is being daily reminded of and is highlighting to a de-sensitised readership is this: at some point poverty becomes a trap such that no amount of normal or routine activity can extract you out of it. Only a serious and literally life-changing intervention can fix that problem.

And here's where I can add: chamas are the routine & normal activity that can address the trap, because they were designed to do exactly that. Which is a solution available to some, and not to others. We had it in Amsterdam in some pre-formative sense. The long term outlook for those with access to these societal techniques is far better than those without. Working to a stronger society then is why I'm working on chamas, with Africans, and not on blockchain with silicon valley types.

I understand that the cost of that is I will be called all sorts of things. But, in this game, it is more important to have clarity of thought than to be liked.

October 23, 2016

Bitfinex - Wolves and a sheep voting on what's for dinner

When Bitcoin first started up, although I have to say I admired the solution in an academic sense, I had two critiques. One is that PoW is not really a sustainable approach. Yes, I buy the argument that you have to pay for security, and it worked so it must be right. But that's only in a narrow sense - there's also an ecosystem approach to think about.

When Bitcoin first started up, although I have to say I admired the solution in an academic sense, I had two critiques. One is that PoW is not really a sustainable approach. Yes, I buy the argument that you have to pay for security, and it worked so it must be right. But that's only in a narrow sense - there's also an ecosystem approach to think about.

Which brings us to the second critique. The Bitcoin community has typically focussed on security of the chain, and less so on the security of the individual. There aren't easy tools to protect the user's value. There is excess of focus on technologically elegant inventions such as multisig, HD, cold storage, 51% attacks and the like, but there isn't much or enough focus in how the user survives in that desperate world.

Instead, there's a lot of blame the victim, saying they should have done X, or Y or used our favourite toy or this exchange not that one. Blaming the victim isn't security, it's cannibalism.

Unfortunately, you don't get out of this for free. If the Bitcoin community doesn't move to protect the user, two things will happen. Firstly, Bitcoin will earn a dirty reputation, so the community won't be able to move to the mainstream. E.g., all these people talking about banks using Bitcoin - fantasy. Moms and pops will be and remain safer with money in the bank, and that's a scary thought if you actually read the news.

Secondly, and worse, the system remains vulnerable to collapse. Let's say someone hacks Mt.Gox and makes a lot of money. They've now got a lot of money to invest in the next hack and the next and the next. And then we get to the present day:

Message to the individual responsible for the Bitfinex security incident of August 2, 2016We would like to have the opportunity to securely communicate with you. It might be possible to reach a mutually agreeable arrangement in exchange for an enormous bug bounty (payable through a more privacy-centric and anonymous way).

So it turns out a hacker took a big lump of Bitfinex's funds. However, the hacker didn't take it all. Joseph VaughnPerling tells me:

"The bitfinex hack took just about exactly what bitfinex had in cold storage as business profit capital. Bitfinex could have immediately made all customers whole, but then would have left insufficient working capital. The hack was executed to do the maximal damage without hurting the ecosystem by putting bitfinex out of business. They were sure to still be around to be hacked again later.It is like a good farmer, you don't cut down the tree to get the apples."

A carefully calculated amount, coincidentally about the same as Bitfinex's working capital! This is annoyingly smart of the hacker - the parasite doesn't want to kill the host. The hacker just wants enough to keep the company in business until the next mafiosa-style protection invoice is due.

So how does the company respond? By realising that it is owned. Pwn'd the cool kids say. But owned. Which means a negotiation is due, and better to convert the hacker into a more responsible shareholder or partner than to just had over the company funds, because there has to be some left over to keep the business running. The hacker is incentivised to back off and just take a little, and the company is incentivised to roll over and let the bigger dog be boss dog.

Everyone wins - in terms of game theory and economics, this is a stable solution. Although customers would have trouble describing this as a win for them, we're looking at it from an ecosystem approach - parasite versus host.

But, that stability only survives if there is precisely one hacker. What happens if there are two hackers? What happens when two hackers stare at the victim and each other?

Well, it's pretty easy to see that two attackers won't agree to divide the spoils. If the first one in takes an amount calculated to keep the host alive, and then the next hacker does the same, the host will die. Even if two hackers could convert themselves into one cartel and split the profits, a third or fourth or Nth hacker breaks the cartel.

The hackers don't even have to vote on this - like the old joke about democracy, when there are 2 wolves and 1 sheep, they eat the sheep immediately. The talk about voting is just the funny part for human consumption. Pardon the pun.

The only stability that exists in the market is if there is between zero and one attacker. So, barring the emergence of some new consensus protocol to turn all the individual attackers into one global mafiosa guild, a theme frequently celebrated in the James Bond movies, this market cannot survive.

To survive in the long run, the Bitcoin community have to do better than the banks - much better. If the Bitcoin community wants a future, they have to change course. They have to stop obsessing about the chain's security and start obsessing about the user's security.

The mantra should be, nobody loses money. If you want users, that's where you have to set the bar - nobody loses money. On the other hand, if you want to build an ecosystem of gamblers, speculators and hackers, by all means, obsess about consensus algorithms, multisig and cold storage.

ps; I first made this argument of ecosystem instability in "Bitcoin & Gresham's Law - the economic inevitability of Collapse," co-authored with Philipp Güring.

March 13, 2016

Elinor Ostrom's 8 Principles for Managing A Commmons

(Editor's note: Originally published at http://www.onthecommons.org/magazine/elinor-ostroms-8-principles-managing-commmons by Jay Walljasper in 2011)

Elinor Ostrom shared the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for her lifetime of scholarly work investigating how communities succeed or fail at managing common pool (finite) resources such as grazing land, forests and irrigation waters. On the Commons is co-sponsor of a Commons Festival at Augsburg College in Minneapolis October 7-8 where she will speak. (See accompanying sidebar for details.)

Ostrom, a political scientist at Indiana University, received the Nobel Prize for her research proving the importance of the commons around the world. Her work investigating how communities co-operate to share resources drives to the heart of debates today about resource use, the public sphere and the future of the planet. She is the first woman to be awarded the Nobel in Economics.

Ostrom’s achievement effectively answers popular theories about the "Tragedy of the Commons", which has been interpreted to mean that private property is the only means of protecting finite resources from ruin or depletion. She has documented in many places around the world how communities devise ways to govern the commons to assure its survival for their needs and future generations.

A classic example of this was her field research in a Swiss village where farmers tend private plots for crops but share a communal meadow to graze their cows. While this would appear a perfect model to prove the tragedy-of-the-commons theory, Ostrom discovered that in reality there were no problems with overgrazing. That is because of a common agreement among villagers that one is allowed to graze more cows on the meadow than they can care for over the winter—a rule that dates back to 1517. Ostrom has documented similar effective examples of "governing the commons" in her research in Kenya, Guatemala, Nepal, Turkey, and Los Angeles.

Based on her extensive work, Ostrom offers 8 principles for how commons can be governed sustainably and equitably in a community.

8 Principles for Managing a Commons

1. Define clear group boundaries.

1. Define clear group boundaries.

2. Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions.

3. Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules.

4. Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities.

5. Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior.

6. Use graduated sanctions for rule violators.

7. Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution.

8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

November 15, 2015

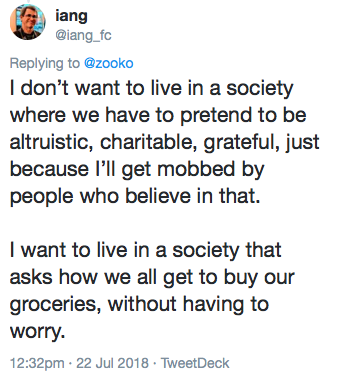

the Satoshi effect - Bitcoin paper success against the academic review system

One of the things that has clearly outlined the dilemma for the academic community is that papers that are self-published or "informally published" to borrow a slur from the inclusion market are making some headway, at least if the Bitcoin paper is a guide to go by.

Here's a quick straw poll checking a year's worth of papers. In the narrow field of financial cryptography, I trawled through FC conference proceedings in 2009, WEIS 2009. For Cryptology in general I added Crypto 2009. I used google scholar to report direct citations, and checked what I'd found against Citeseer (I also added the number of citations for the top citer in rightmost column, as an additional check. You can mostly ignore that number.) I came across Wang et al's paper from 2005 on SHA1, and a few others from the early 2000s and added them for comparison - I'm unsure what other crypto papers are as big in the 2000s.

| Conf | paper | Google Scholar | Citeseer | top derivative citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| jMLR 2003 | Latent dirichlet allocation | 12788 | 2634 | 26202 |

| NIPS 2004 | MapReduce: simplified data processing on large clusters | 15444 | 2023 | 14179 |

| CACM 1981 | Untraceable electronic mail, return addresses, and digital pseudonyms | 4521 | 1397 | 3734 |

| self | Security without identification: transaction systems to make Big Brother obsolete | 1780 | 470 | 2217 |

| Crypto 2005 | Finding collisions in the full SHA-1 | 1504 | 196 | 886 |

| SIGKDD 2009 | The WEKA data mining software: an update | 9726 | 704 | 3099 |

| STOC 2009 | Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices | 1923 | 324 | 770 |

| self | Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system | 804 | 57 | 202 |

| Crypto09 | Dual System Encryption: Realizing Fully Secure IBE and HIBE under Simple Assumptions | 445 | 59 | 549 |

| Crypto09 | Fast Cryptographic Primitives and Circular-Secure Encryption Based on Hard Learning Problems | 223 | 42 | 485 |

| Crypto09 | Distinguisher and Related-Key Attack on the Full AES-256 | 232 | 29 | 278 |

| FC09 | Secure multiparty computation goes live | 191 | 25 | 172 |

| WEIS 2009 | The privacy jungle: On the market for data protection in social networks | 186 | 18 | 221 |

| FC09 | Private intersection of certified sets | 84 | 24 | 180 |

| FC09 | Passwords: If We’re So Smart, Why Are We Still Using Them? | 89 | 16 | 322 |

| WEIS 2009 | Nobody Sells Gold for the Price of Silver: Dishonesty, Uncertainty and the Underground Economy | 82 | 24 | 275 |

| FC09 | Optimised to Fail: Card Readers for Online Banking | 80 | 24 | 226 |

What can we conclude? Within the general infosec/security/crypto field in 2009, the Bitcoin paper is the second paper after Fully homomorphic encryption (which is probably not even in use?). If one includes all CS papers in 2009, then it's likely pushed down a 100 or so slots according to citeseer although I didn't run that test.

If we go back in time there are many more influential papers by citations, but there's a clear need for time. There may well be others I've missed, but so far we're looking at one of a very small handful of very significant papers at least in the cryptocurrency world.

It would be curious if we could measure the impact of self-publication on citations - but I don't see a way to do that as yet.

Ledger - a journal for cryptocurrency papers

"Ledger" was recently announced as a journal for cryptocurrency papers, and the timing was rather spectacular. Everyone agrees this is a good idea.

Today I had a look, because I and some friends have some papers that might be published there. Several things reached out, so I thought I'd put them out here and see if they resonate.

1. The Ledger team seem to have taken on some criticism of the academic process and gone for more openness in several areas:

- Ledger has created a peer review system where reviews are publishable by authors. What Ledger have done is ensured that reviewers can be published and held accountable for their reviews. This should go some way to stopping academic cliques building up, a fate that I can attest to directly.

- Papers are CC-licensed so immediately and popularly available. Discourse is well served. I am not sure where the others are now, but I've had my arguments in the past with the proxies of Springer-Verlag wanting to own my mind. Those days are dead.

- Fast turn arounds promised.

2. Business-wise, Ledger is a direct competitor to existing forums Financial Cryptography (the conference) and to a lesser extent WEIS. Now, this is fine in my view as (a) the space has massively enlarged from the niche it once was, and we can easily support more forums, and (b) Ledger is oriented to the paper distribution process whereas others are primarily presentation-oriented and networking. Also (c) the founder and coiner of Financial Cryptography, Bob Hettinga, always made clear that this was a competitive market ;)

3. It is not immediately clear who the reviewers are. While the core might be its Editorial base, the asset of a peer-reviewed journal is its hardworking reviewers. Specifically, the asset can be attached.

4. And, immediately the attachment begins. If you look at the Editor's page, they have fallen into the same trap as the financial cryptography conference fell into in 1998 - academic control. Of the very long list of fine editors, only a tiny minority are outside the University system by either affiliation or title. Whatever you think of the academic world, it is very clear that it is a discriminatory system, and many fine contributions are squashed or stolen for it.

5. In which world, reputation and cites rule. Which leads to anonymous authorship:

Under extenuating circumstances, the journal may permit authors to publish under a pseudonym. Authors should include a statement describing why they wish to remain anonymous at the time of article submission. Only manuscripts where quality can be judged exclusively from the content presented in the paper, and where the scope of any conflict of interest problems would be limited (should they exist), will be considered for anonymous authorship.

Ledger are clearly skeptical of the notion of anonymous authorship because as academics they are so used to leaning on the reputation of the author. A bad paper by a leading author always trumps a good paper by an unknown, and it is practically the law that the profs must co-author the papers of the candidates so as to cross that barrier.

Ledger are thus clearly skeptical that the paper's words mean much independently of the author's reputation. Leaving it at odds with the Bitcoin community is as it is, as, under those rules, Satoshi's paper would not have been published, and we'd not be having these discussions. Now, it's fine for them to do this, but what I'd point out here is that this is further evidence of 4. above: academics setting themselves up to capture cites.

6. In not charging for papers, nor distribution & access, the Ledger has a clear financial business problem. It (probably) relies entirely on two sources: the volunteer time of reviewers, and the paid salary of academics.

The nature of scientific enquiry has moved on since the days of the controlled paper distribution. All papers from now on must be free of economic control, or we get the Satoshi effect - the most important paper in the field was never published in a forum, because under the rules of all the forums, it could not be published. The old forums out there had economic controls, and those controls were captured by the very people who could benefit from the controls - cites are promotions are money, and paper is trees is subscriptions.

Ledger presents the disturbing academic dilemma in a nutshell. The Internet has solved the paper-subscription economic barrier, but not the citation-peer-review circle. And, it leans very heavily on academics on salary, which is the other side of the same coin - what is the economic model that both sustains the machine, and rewards the quality?

If you're thinking I'm arguing both sides of this - you're right. I can see the problem. I don't have the answers - unless you want something superficial like "publish papers on the blockchain!" But we won't find the answers until we understand the problems.

October 25, 2015

When the security community eats its own...

If you've ever wondered what that Market for Silver Bullets paper was about, here's Pete Herzog with the easy version:

When the Security Community Eats Its Own

BY PETE HERZOG

http://isecom.org

The CEO of a Major Corp. asks the CISO if the new exploit discovered in the wild, Shizzam, could affect their production systems. He said he didn't think so, but just to be sure he said they will analyze all the systems for the vulnerability.

So his staff is told to drop everything, learn all they can about this new exploit and analyze all systems for vulnerabilities. They go through logs, run scans with FOSS tools, and even buy a Shizzam plugin from their vendor for their AV scanner. They find nothing.

A day later the CEO comes and tells him that the news says Shizzam likely is affecting their systems. So the CISO goes back to his staff to have them analyze it all over again. And again they tell him they don’t find anything.

Again the CEO calls him and says he’s seeing now in the news that his company certainly has some kind of cybersecurity problem.

So, now the CISO panics and brings on a whole incident response team from a major security consultancy to go through each and every system with great care. But after hundreds of man hours spent doing the same things they themselves did, they find nothing.

He contacts the CEO and tells him the good news. But the CEO tells him that he just got a call from a journalist looking to confirm that they’ve been hacked. The CISO starts freaking out.

The CISO tells his security guys to prepare for a full security upgrade. He pushes the CIO to authorize an emergency budget to buy more firewalls and secondary intrusion detection systems. The CEO pushes the budget to the board who approves the budget in record time. And almost immediately the equipment starts arriving. The team works through the nights to get it all in place.

The CEO calls the CISO on his mobile – rarely a good sign. He tells the CISO that the NY Times just published that their company allegedly is getting hacked Sony-style.

They point to the newly discovered exploit as the likely cause. They point to blogs discussing the horrors the new exploit could cause, and what it means for the rest of the smaller companies out there who can’t defend themselves with the same financial alacrity as Major Corp.

The CEO tells the CISO that it's time they bring in the FBI. So he needs him to come explain himself and the situation to the board that evening.

The CISO feels sick to his stomach. He goes through the weeks of reports, findings, and security upgrades. Hundreds of thousands spent and - nothing! There's NOTHING to indicate a hack or even a problem from this exploit.

So wondering if he’s misunderstood Shizzam and how it could have caused this, he decides to reach out to the security community. He makes a new Twitter account so people don’t know who he is. He jumps into the trending #MajorCorpFail stream and tweets, "How bad is the Major Corp hack anyway?"

A few seconds later a penetration tester replies, "Nobody knows xactly but it’s really bad b/c vendors and consultants say that Major Corp has been throwing money at it for weeks."

Read on for the more deeper analysis.

October 22, 2015

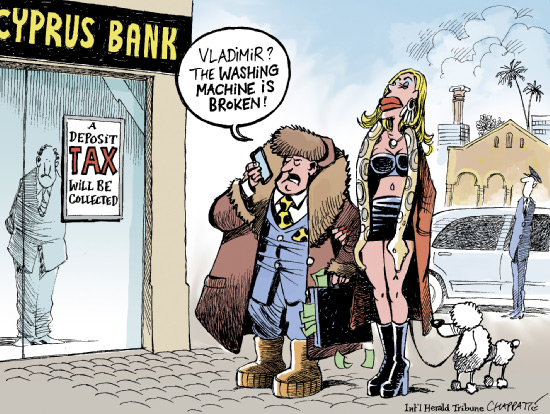

Iceland puts more bankers in jail... what's your solution to the financial crisis?

In the crisis that just won't go away - we're effectively in depression but no politician can stay elected on that platform - one of the most watched countries is Iceland.

Iceland sentences 26 bankers to a combined 74 years in prison James Woods October 21, 2015 Unlike the Obama administration, Iceland is focusing on prosecuting the CEOs rather than the low-level traders.In a move that would make many capitalists' head explode if it ever happened here, Iceland just sentenced their 26th banker to prison for their part in the 2008 financial collapse.

In two separate Icelandic Supreme Court and Reykjavik District Court rulings, five top bankers from Landsbankinn and Kaupping — the two largest banks in the country — were found guilty of market manipulation, embezzlement, and breach of fiduciary duties. Most of those convicted have been sentenced to prison for two to five years. The maximum penalty for financial crimes in Iceland is six years, although their Supreme Court is currently hearing arguments to consider expanding sentences beyond the six year maximum.

Now, my argument here is the same as with the audit cycle: if so much was so wrong, surely some bankers in USA and Europe should have been prosecuted and put in jail even by accident?

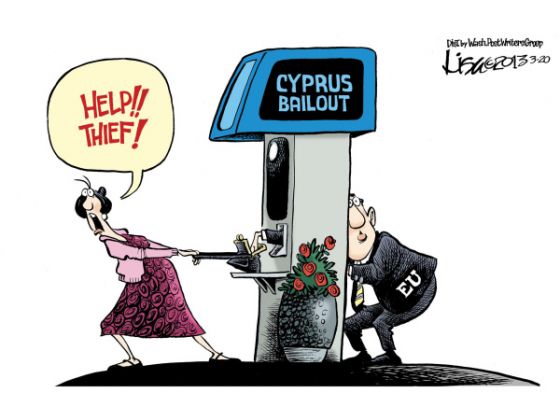

But, no, nothing. A few desultory insider trading hits, but on the whole, a completely clean pass for the major banks. Coupled with direct bankrupcy bailouts, and the follow-on enormous bailout of QE* which transferred capital into the banks under deception plan of "re-inflating industry", we have a rather unfortunate situation:

No punishment means no sin, right?

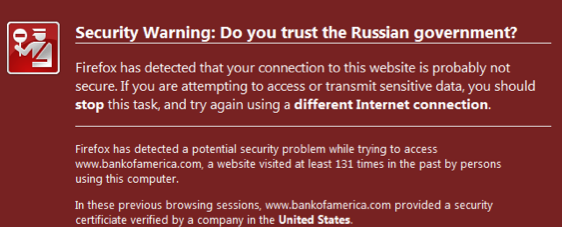

It is no wonder that the public at large are unhappy with banking in general and are willing to entertain such way out ideas as blockchain. Credibility is a huge issue:

When Iceland's President, Olafur Ragnar Grimmson was asked how the country managed to recover from the global financial disaster, he famously replied,"We were wise enough not to follow the traditional prevailing orthodoxies of the Western financial world in the last 30 years. We introduced currency controls, we let the banks fail, we provided support for the poor, and we didn’t introduce austerity measures like you're seeing in Europe."

A great time to be an economic historian. A middling time to be an economist. Terrible time to be a regulator?

June 28, 2015

The Nakamoto Signature

The Nakamoto Signature might be a thing. In 2014, the Sidechains whitepaper by Back et al introduced the term Dynamic Membership Multiple-party Signature or DMMS -- because we love complicated terms and long impassable acronyms.

Or maybe we don't. I can never recall DMMS nor even get it right without thinking through the words; in response to my cognitive poverty, Adam Back suggested we call it a Nakamoto signature.

That's actually about right in cryptology terms. When a new form of cryptography turns up and it lacks an easy name, it's very often called after its inventor. Famous companions to this tradition include RSA for Rivest, Shamir, Adleman; Schnorr for the name of the signature that Bitcoin wants to move to. Rijndael is our most popular secret key algorithm, from the inventors names, although you might know it these days as AES. In the old days of blinded formulas to do untraceable cash, the frontrunners were signatures named after Chaum, Brands and Wagner.

On to the Nakamoto signature. Why is it useful to label it so?

Because, with this literary device, it is now much easier to talk about the blockchain. Watch this:

The blockchain is a shared ledger where each new block of transactions - the 10 minutes thing - is signed with a Nakamoto signature.

Less than 25 words! Outstanding! We can now separate this discussion into two things to understand: firstly: what's a shared ledger, and second: what's the Nakamoto signature?

Each can be covered as a separate topic. For example:

the shared ledger can be seen as a series of blocks, each of which is a single document presented for signature. Each block consists of a set of transactions built on the previous set. Each succeeding block changes the state of the accounts by moving money around; so given any particular state we can create the next block by filling it with transactions that do those money moves, and signing it with a Nakamoto signature.

Having described the the shared ledger, we can now attack the Nakamoto signature:

A Nakamoto signature is a device to allow a group to agree on a shared document. To eliminate the potential for inconsistencies aka disagreement, the group engages in a lottery to pick one person's version as the one true document. That lottery is effected by all members of the group racing to create the longest hash over their copy of the document. The longest hash wins the prize and also becomes a verifiable 'token' of the one true document for members of the group: the Nakamoto signature.

That's it, in a nutshell. That's good enough for most people. Others however will want to open that nutshell up and go deeper into the hows, whys and whethers of it all. You'll note I left plenty of room for argument above; Economists will look at the incentive structure in the lottery, and ask if a prize in exchange for proof-of-work is enough to encourage an efficient agreement, even in the presence of attackers? Computer scientists will ask 'what happens if...' and search for ways to make it not so. Entrepreneurs might be more interested in what other documents can be signed this way. Cryptographers will pounce on that longest hash thing.

But for most of us we can now move on to the real work. We haven't got time for minutia. The real joy of the Nakamoto signature is that it breaks what was one monolithic incomprehensible problem into two more understandable ones. Divide and conquer!

The Nakamoto signature needs to be a thing. Let it be so!

NB: This article was kindly commented on by Ada Lovelace and Adam Back.

June 17, 2015

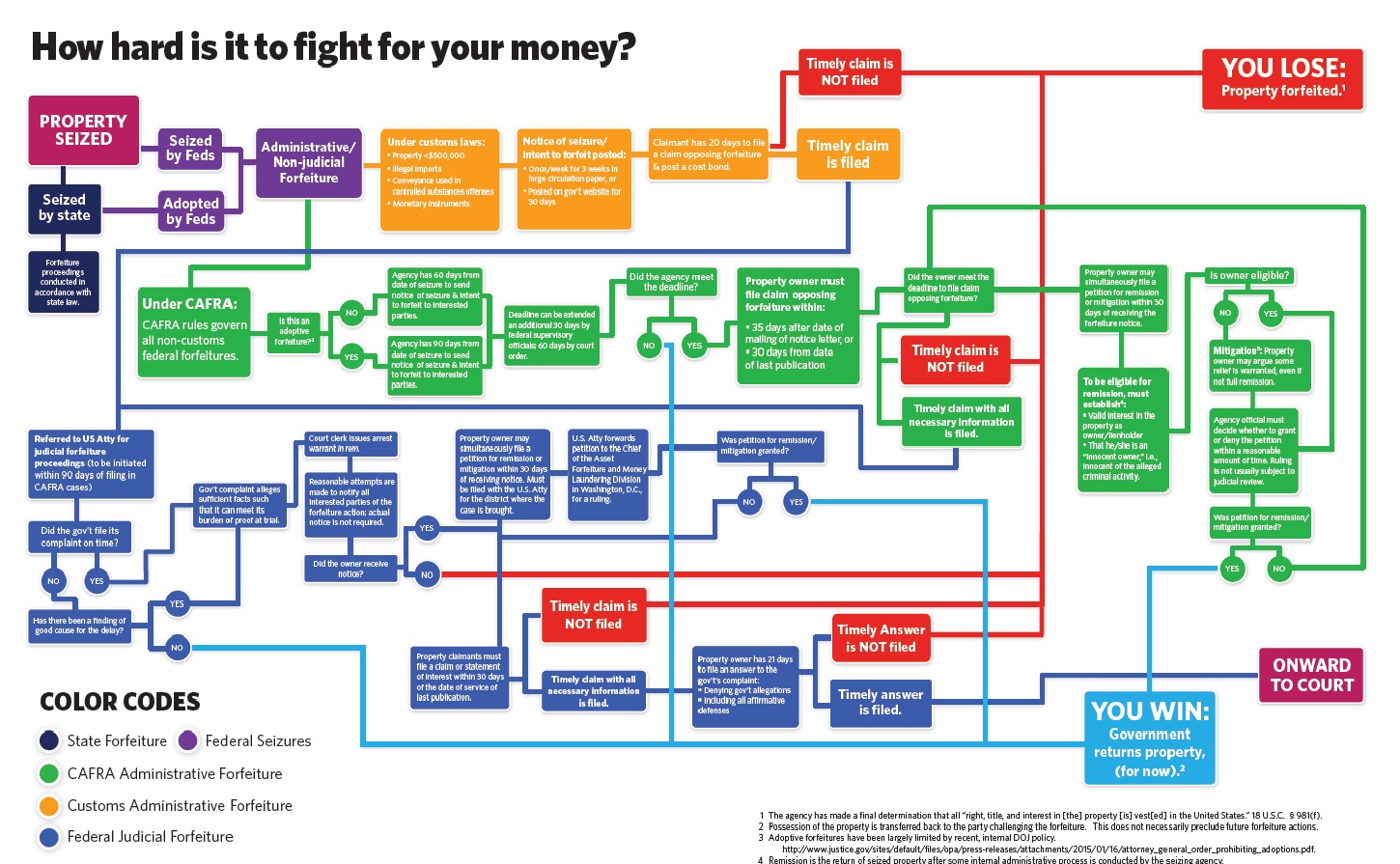

Cash seizure is a thing - maybe this picture will convince you

There are many many people who do not believe that the USA police seize cash from people and use it for budget. The system is set up for the benefit of police - budgetary plans are laid, you have no direct recourse to the law because it is the cash that defends itself, the proceeds are carved up.

Maybe this will convince you - if cash seizure by police wasn't a 'thing' we wouldn't need this chart:

June 09, 2015

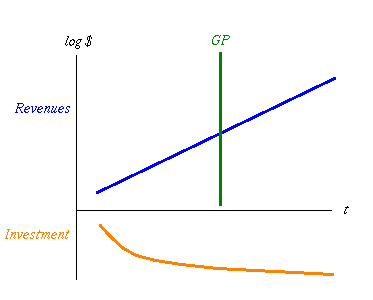

Equity Crowd Funding - why it will change everything

Editor here again, picking up part 2 of the crowd funding thread. In the previous post, Vinay Gupta laid out why Coase's theorem didn't predict the tech revolution quite yet - in a nutshell, we lacked some critical components, of which one was the blockchain, being that invention that allows a dynamic membership multi-party signature (DMMS) to create a single entry that rules all others, the part I called triple entry.

But is it the only missing component? No. Actually, there's another component we are missing, and it is this: the ability to acquire the capital to build what we need and want. That hinted at, let's continue...

Vinay Gupta says:

Does everyone have a clear idea what Equity Crowd Funding looks like?

You get a bucket, everyone puts in 20 quid, everyone gets a tiny share in the company, if the company turns out to be the next eBay, you get 2000 quid back.

"Eh? Huh? What? I thought you never got anything back from most of the crowd funding sites?"

Aha! *Equity* crowd funding! Equity!

In Regular crowd funding, you put the money in and nothing comes back. In *equity* crowd funding, you put the money in and a tiny share comes back. And you can actually make some real money!

"I just missed the equity word."

Now, *equity* crowd funding is obviously a good idea. It is very very very hard to find any rational argument as to why equity crowd funding is a bad idea. The only objections you will typically see is, what if the public get conned. And that, coming from governments that actually operate national lotteries.

Right? Pardon? What are you talking about?!

"Bingo!"

You allow people to sell cigarettes, what are you talking about, "The public will get conned!" You're mad!

So, there are some quality control problems with equity crowd funding as a model. You need some way to communicate to people the level of risk in an appropriate way. You might want to talk about reputational rating systems. A Moodys or a Standard&Poors for equity crowd funding might be a good idea. There's all kinds of stuff you might want to do.

The basic idea is obviously sound. You sit there with a credit card, you swipe it, you own a tiny little share in a company that's manufacturing some weird looking device that you clip to a golf club, and if tens of millions of people like it, you make a lot of money back.

It's just not done.

Right now, the regulatory frameworks around equity crowd funding cripple it, and this is I think the key fight for the development of technology in the 21st century.

If we win equity crowd funding, I think we get pretty much a flying car each. And if we lose on equity crowd funding, I think we are potentially on a long cycle of decline, into a kind of neo-feudal patent-barren landscape.

Bold stuff!

Back to me. This pretty much nails *what* equity crowd funding is, and suggests the transition as to why it is going to be a killer app on the blockchain. (For the *why* of it you'd have to listen to the whole talk, and for the inter-relations you'd have to see a whole lot more stuff.)

The interesting thing, once we've got that understanding, that position, is to question how it will develop. We're in a race, or if we're not in it, we're watching it. At a simplistic level, it is a race between existing players trying to deregulate conventional securities issues fast enough, versus new players (we've maybe not seen yet) creating it fully openly on the blockchain.

It's not clear who is going to win. OK, what is clear is that the people win because we win more stuff for less money; but it is not clear whether we the people win all the way, or only a partial victory.

Do we get a flying car, each, or do we enter neo-feudal patent-barren secular decline?

Where are you on this race? Are you ready to bet?

May 01, 2015

Proof of Work is now being put to work - toasters!

FtAlpahville's has just revealed what revealing that 21Inc (formerly 21e6) are doing exactly that.

Its core business plan it turns out will be embedding ASIC bitcoin mining chips into everyday devices like USB battery chargers, routers, printers, gaming consoles, set-top boxes and -- the piece de resistance -- chipsets to be used by internet of things devices.21 Inc wants to put your toaster to work, forging our cryptocurrency future.

Interesting, because 21Inc currently holds the record for the biggest funding round - 116 million dollars! Here although the link will not last long.

It seems like the notion of heating ones house with residual heat from Bitcoin mining has been around for a long term, see slashdot from 2011.12.21, Gavin Andresen from 2013.04.09:

I can imagine bitcoin-mining electric hot water heaters installed in homes all across the world, installed by thousands of private companies that split the profits with homeowners.

More: FTAlphaville from 2014.09.05 which calls it "the latest fad." Vitalik Buterin also spotted the security argument in 2012.02.28:

"If miners figure out that they can dual-use their mining electricity by making their computers heat their homes during the winter, that would be a very positive change since it would decentralize mining to something every home or business does rather than a task done by centralized, specialized supercomputers and it would increase the network's hash power and thus security but it would not ultimately reduce the mining cost."

This all by the way of linking to some musings I wrote back in 2014, late to the game it seems, and maybe calling a fad was accurate. What seems clear is that the world is not happy about the efficiency of Bitcoin, and until this is addressed more comprehensively, the bitcoin core will stand at odds with the world. E.g. This might be the wrong moment in history to tell the mass market that our solution to the banking crisis is to gratuitously waste energy.

April 05, 2015

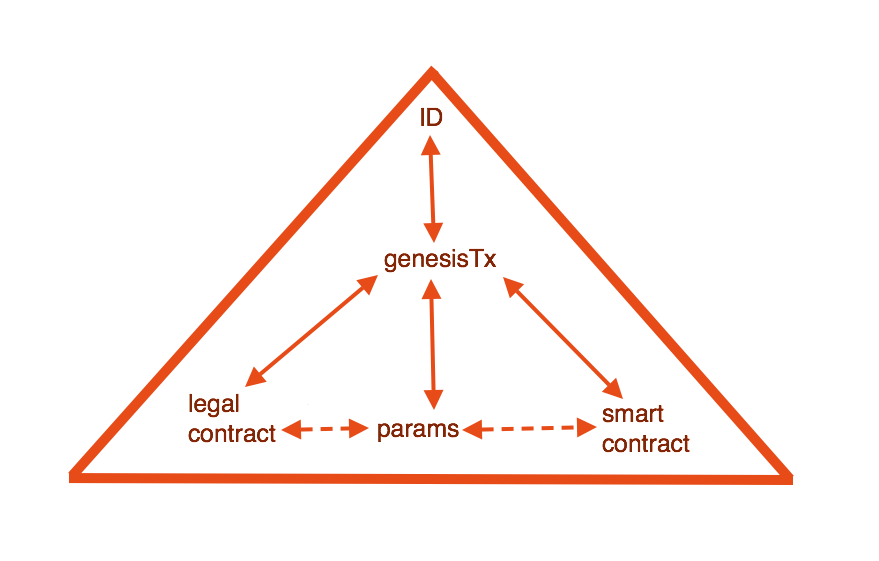

Yanis Varoufakis proposes Greek tax receipts in Ricardian Contracts on a blockchain

The answer is yes: They can create their own payment system backed by future taxes and denominated in euros. Moreover, they could use a Bitcoin-like algorithm in order to make the system transparent, efficient and transactions-cost-free. Let's call this system FT-coin; with FT standing for... Future Taxes.FT-coin could work as follows:

- You pay, say, €1000 to buy 1 FT-coin from a national Treasury's website (Spain, Italy, Ireland etc. would run their separate FT-coin markets) under a contract that binds the national Treasury: (a) to redeem your FT-coin for €1000 at any time or (b) to accept your FT-coin two years after it was issued as payment that extinguishes, say, €1500 worth of taxes.

- Each FT-coin is time stamped i.e. in its code the date of issue is contained and can be used to check that it is not used to extinguish taxes before two years have passed.

- Every year (after the system has been operating for at least two years) the Treasury issues a new batch of FT-coins to replace the ones that have been extinguished (as taxpayers use them, two years after the system's inauguration, to pay their taxes) on the understanding that the nominal value of the total number of FT-coins in circulation does not exceed a certain percentage of GDP (e.g. 10% of nominal GDP so that there is no danger that, if all FT-coins are redeemed simultaneously, the government will end up, during that year, with no taxes).

That first bullet point (my emphasis) is a legal issuance of new value, a.k.a., a bond, a.k.a. a contract of issuance. The offering concept is the same as the tally sticks of old - selling the pre-payment of taxes at a discount, the technicalities are simply how we get a legal contract into a digital framework that accounts for many similar values.

Because it's a contract in law as opposed to say a smartcontract, we need a system that can handle legal contracts. In essence, this is the Ricardian Contract -- a device that takes a human prose and encapsulates it into a hard computer-readable and human-readable document, then gives you a unique identifier in order to allow a technical system of issuance such as Bitcoin to do its job.

We're not there yet - Bitcoin directly isn't good enough, as Bitcoin is only "the one" BTC and therefore has no need to describe another. Hence no contract.

But the newer "generation 2.0" systems are more capable of including the Ricardian Contract form, and some do already while others can do so with minimal tweaking. This means that if Yanis Varoufakis is serious about his ideas, and given recent news from say IBM, there is no reason not to be, he'll be looking at a generation 2.0 system such as those described at WebFunds.

For Bitcoin itself, all is not lost, but it's more of a future deliverable: variants are looking at it but I have no definite information on that. However, there is no doubt that this will come, as Yanis Varoufakis is not the first. At least half the corporate and big players out there say "we can't use Bitcoin because it lacks a contract of issuance" or words to effect.

April 03, 2015

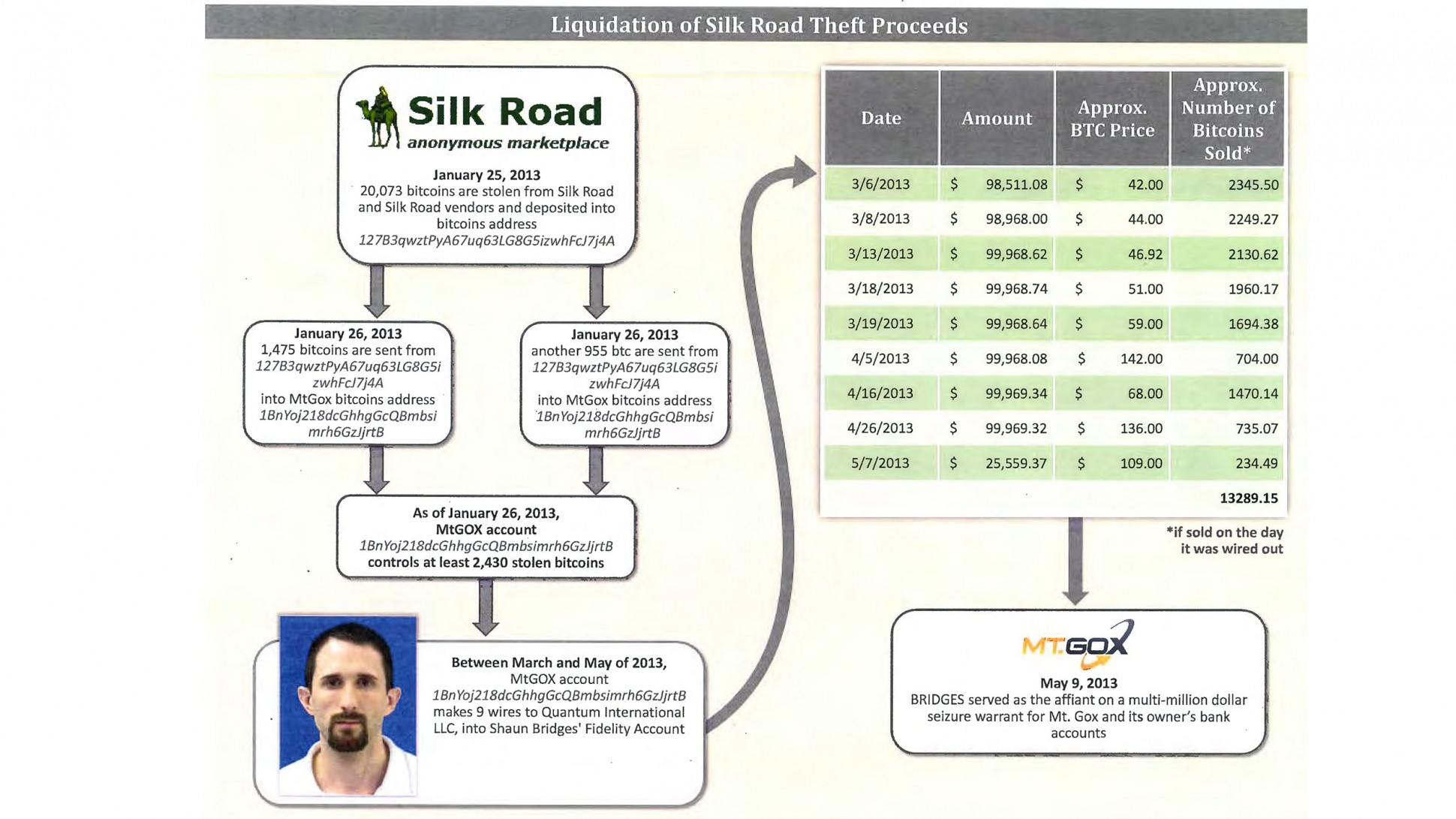

Training Day 2: starring Bridges & Force

Readers might have probably been watching the amazing story of the Bridges & Force arrests in USA. It's starting to look much like a film, and the one I have in mind is this: Training Day.

Readers might have probably been watching the amazing story of the Bridges & Force arrests in USA. It's starting to look much like a film, and the one I have in mind is this: Training Day.

In short: two agents were sent in to bring down the Silk Road website for selling anything (guns, drugs, etc). In the process, the agents stole a lot of the money. And in the process, went on a rampage through the Bitcoin economy robbing, extorting, and manipulating their way to riches.

You can't make this up. Worse, we don't need to. The problem is deep, underlying and demented within our society. We're going to see much more of it, and the reason we know this is that we have decades of experience in other countries outside the OECD purview.

This is our own actions coming back to destroy us. In a nutshell here it is, here is the short story that gets me on the FATF's blacklist and you too if you spread it:

In the 1980s, certain European governments got upset about certain forms of arbitrage across nations by multinationals and rich folk. These people found a ready consensus with others in policing work who said that "follow the money" was how you catch the really bad people, a.k.a. criminals. Between these two groups of public servants they felt they could crack open the bank secrecy that was protecting criminals and rich people alike.

So the Anti Money Laundering or AML project was born, under the aegis of FATF or financial action task force, an office created in Paris under OECD. Their concept was that they put together rules about how to stop bad money moving through the system. In short: know your customer, and make sure their funds were good. Add in risk management and suspicious activity reporting and you're golden.

On passing these laws, every politician faithfully promised it was only for the big stuff, drugs and terrorism, and would never be used against honest or wealthy or innocent people. Honest Injun!

If only so simple. Anyone who knows anything about crime or wealth realises within seconds that this is not going to achieve anything against the criminals or the wealthy. Indeed, it may even make matters worse, because (a) the system is too imperfect to be anything but noise, (b) criminals and wealthy can bypass the system, and (c) criminals can pay for access. Hold onto that thought.

So, if the FATF had stopped there, then AML would have just been a massive cost on society. Westerners would paid basis points for nothing, and it would have just been a tool that shut the poor out of the financial system; something some call the problem of the 'unbanked' but that's a subject for another day (and don't use that term in my presence, thanks!). Criminals would have figured out other methods, etc.

If only. Just. But they went further.

In imposing the FATF 40 recommendations (yes, it got a lot more complicated and detailed, of course) everyone everywhere everytime also stumbled on an ancient truth of bureaucracy without control: we could do more if we had more money! Because of course the society cost of following AML was also hitting the police, implementing this wonderful notion of "follow the money" cost a lot of money.

Until someone had the bright idea: if the money is bad, why can't we seize the bad money and use it to find more bad money?

Until someone had the bright idea: if the money is bad, why can't we seize the bad money and use it to find more bad money?

And so, it came to pass. The centuries-honoured principle of 'consolidated revenue' was destroyed and nobody noticed because "we're stopping bad people." Laws and regs were finagled through to allow money seized from AML operations to be then "shared" across the interested good parties. Typically some goes to the local police, and some to the federal justice. You can imagine the heated discussions about percentage sharing.

What could possibly go wrong?

Now the police were empowered not only to seize vast troves of money, but also keep part of it. In the twinkling of an eye, your local police force was now incentivised to look at the cash pile of everyone in their local society and 'find' a reason to bust. And, as time went on, they built their system to be robust to errors: even if they were wrong, the chances of any comeback were infinitesimal and the take might just be reduced.

AML became a profit center. Why did we let this happen? Several reasons:

1. It's in part because "bad guys have bad money" is such a compelling story that none dare question those who take "bad money from bad guys."

Indeed, money laundering is such a common criminal indictment in USA simply because people assume it's true on the face of it. The crime itself is almost as simple as moving a large pot of money around, which if you understand criminal proceedings, makes no sense at all. How can moving a large pot of money around be proven as ML before you've proven a predicate crime? But so it is.

2. How could we as society be so stupid? It's because the principle of 'consolidated revenue' has been lost in time. The basic principle is simple: *all* monies coming into the state must go to the revenue office. From there they are spent according to the annual budget. This principle is there not only for accountability but to stop the local authorities becoming the bandits The concept goes back all the way to the Magna Carta which was literally and principally about the barons securing the rights to a trial /over arbitrary seizure of their wealth/.

We dropped the ball on AML because we forgot history.

So what's all this to do with Bridges & Force? Well, recall that thought: the serious criminals can buy access. Which of course they've been doing since the beginning, the AML authorities themselves are victims to corruption.

As the various insiders in AML are corrupted, it becomes a corrosive force. Some insiders see people taking bribes and can't prove anything. Of course, these people aren't stupid, these are highly trained agents. Eventually they work out how they can't change anything and the crooks will never be ousted from inside the AML authorities. And they start with a little on the side. A little becomes a lot.

Every agent in these fields is exposed to massive corruption right from the start. It's not as if agents sent into these fields are bad. Quite the reverse, they are good and are made bad. The way AML is constructed it seems impossible that there could be any other result - Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? or Who watches the watchers?

Remember the film Training Day ? Bridges and Force are a remake, a sequel, this time moved a bit further north and with the added sex appeal of a cryptocurrency.

But the important things to realise is that this isn't unusual, it's embedded. AML is fatally corrupted because (a) it can't work anyway, and (b) they breached the principle of consolidated revenue, (c) turned themselves into victims, and then (d) the bad guys.

Until AML itself is unwound, we can't ourselves - society, police, authorities, bitcoiners - get back to the business of fighting the real bad guys. I'd love to talk to anyone about that, but unfortunately the agenda is set. We're screwed as society until we unwind AML.

March 30, 2015

Smart contracts are a centralising force - exactly the opposite effect to the one you hoped for?

@gendal writes on smart contracts and as usual his words are prophetic and dangerous:

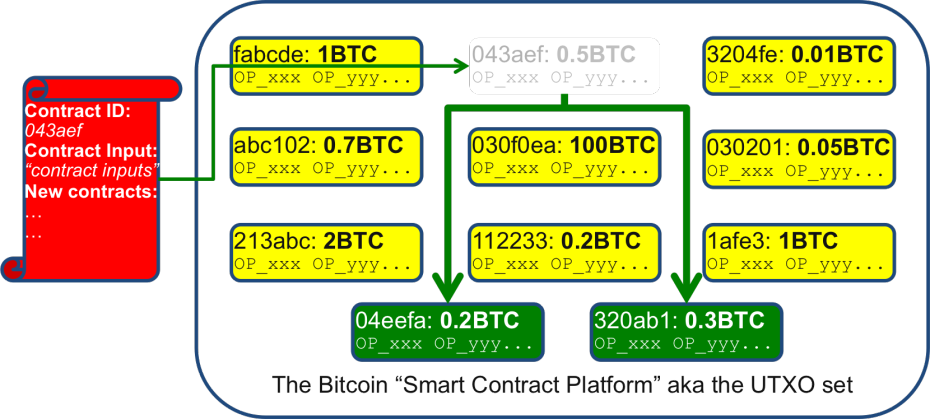

Bitcoin as a currency might be to miss the pointFor me, it is a mistake to think about Bitcoin solely as a currency. Because the Bitcoin currency system is a masterclass in mirage: underneath the hood, it's a fascinating smart contract platform.

Or, as I said at the Financial Services Club, every time you make a Bitcoin payment, you're actually asking over 6000 computers around the world to run a small computer program for you... and your only task is to make sure that the computer program returns "TRUE". Within the Bitcoin community, this is well-known, of course. Indeed, the work done by Mike Hearn and others to document the platform's capabilities has been around for years. But I find most people in the broader debate are unaware that the platform is pretty much built on this capability -- it's not an add-on.

He then goes on to describe the smart contract within the Bitcoin system as two programs: one of which comes from the past, and the other of which is your proving program to say you can get access. Out of this we build payments: each new program sets up an unspent transaction output for the next program, run by your recipient, to prove she is a recipient and can further send the funds.

He then goes on to describe the smart contract within the Bitcoin system as two programs: one of which comes from the past, and the other of which is your proving program to say you can get access. Out of this we build payments: each new program sets up an unspent transaction output for the next program, run by your recipient, to prove she is a recipient and can further send the funds.

Makes sense? Do not be afraid to say it is a bit tricky, and this is the theme I'm developing on. Have a read of @gendal's description and see if you're any the wiser.

Now, I have always eschewed smart contracts because I'm a-feared of their potency "But notice how powerful this is... because the other thing you do is..." and he goes on:

So what does this have to do with smart contracts? The key is that the model I outlined above is quite generic. The programming language is (just about) powerful enough to implement some interesting business logic that goes beyond "Richard paying money to Bob". For example, you can write a program that will only return "TRUE" if you provide proof that you know the private key to multiple bitcoin addresses. This is a way to model "a majority of Board Directors must jointly sign before these funds can be spent", perhaps. The Bitcoin "contracts" wiki page goes into far more depth.

What has got the Bitcoin community so excited is that these smart contracts are *really powerful*. This has led to several rather perverse and contradictory effects which I'll try and list out:

- Firstly, geeks have gone into the smart contracts with expectations of writing very powerful things. Mike Hearn for example has gone for crowd-funding in smart contracts, a business line I heartily approve of (since 1997)!

- However, in contrast to the hype we've only really seen a very small puff of a possibility: the multisig. Not the explosion of possibilities that the hype predicts.

- Perhaps as a response to this Ethereum and others are building the blockchains to run smart contracts in the full vision as promised.

- Now let me drift along here a bit. Smart contracts are like programming, and programming is difficult. So much so that we typically send kids off to university to study the stuff for 4 years before letting them loose on small parts of commercial systems.

- This time, we've got "programming" added to "money". Indeed I call them state machines with money . Double trouble - so we can imagine that this is also going to become a very specialised and tricky area, and it was this combination of explosive elements (including the net, crypto, accounting, etc) that caused the 1990s oldtimers to coin the phrase financial cryptography.

- Now's the time to include the link to the team that writes space shuttle software, because when things go wrong in this area the consequences can be devastating.

My point here isn't that you the Bitcoin geek will find it beyond you. Actually more subtle than this: you will find that you actually do write a smart contract, and it's a lot of fun.

But, others do too. And others do better, as a consequence of the hollywood/star effect, or the grass is always greener. So, you'll be overtaken, and if you're not careful, you lose as well. Money.

This all leads to what the economists call economies of scale . Which is to say that assuming smart contracts are about to take off, we are actually not looking at an empowering technology that returns finance to the people, but quite the reverse: an arms race where the corporation that can muster the most human capital to write these complicated things will dominate.

Or, the government.

Smart contracts are a centralising force, not a decentralising force. Once they get going, they may be unstoppable. Yes you can write your own, but in the same way as you can write your own operating system. Hell, Linus did it, right? But that's part of the point, the only reason you know his name is because he actually succeeded and the other 10000 people who tried this in the 1980s are forgotten.

So in contrast to the normal libertarian rhetoric around self-empowerment, the people's finance, up against the government, what are we likely to see?

As systems start to take off, smart operators will collect groups of programmers and collect their combined effort into frameworks. Which they will sell to customers. It takes capital to do that, so VCs take note of this play, and recall that my day rate is not exorbitant.

These groups will compete and combine .. until we end up with the larger group that can do it all. Is this a market of naturally 4 players (like banks, mobile, accounting) or naturally one player (guilds, landline, governments) ? I don't know yet, but watch for the IPOs.

The libertarians and geeks will rise up and say "open source!" It will be open and empowered and free. Shrug. Have a look at SSL. It's open source, but it is totally and utterly controlled by a few huge corporations: The browsers, the CAs, the Redhats and Akamai's of the world. That's because there are such economies of scale that it takes real capital to bring together the elements to control and build these systems end-to-end. And these companies mob the committees and RFCs and make sure their apple cart is not upset.

Complexity it turns out is not only the enemy of security, it's the enemy of individual empowerment, freedom to contract and all that.

What to do about this? I've written before about the problem of funding the developers in open source projects. It may be that there is still room to "do smart contracts right." In this sense I'm envisaging something like the Blockstream play, which is a company that has collected many of the Bitcoin experts, but it has been financed explicitly by Reid Hoffman on the basis that "we have to do it right, to preserve the commons." This stands in contrast to the efforts of Ethereum and others that are building their platforms as without the limitations of the bitcoin network and without their philosophical guidance: weaponised smart contracts, ready to go.

Maybe there is a play like that which is possible for smart contracts? I don't know. But I do know that the future starts with understanding the forces pushing on the present, and the smart contract does not represent decentralisation but instead will lead to massive centralisation of programming power.

In this sense it's like every other great enabling technology: gunpowder led to cannons, steam led to railroads to WWI, the internet led to cyberwarfare, all stories of centralisation. What can we do to keep smart contracts from not turning into a future disaster against us all?

March 11, 2015

I'm so stupid - The market for aid is a Spence insufficient information market

I just figured it out, in a flash: Aid is Spencian.

I just figured it out, in a flash: Aid is Spencian.

3 years after my Kenyan adventure started, and I feel like I've got the intellectual dexterity of a slug. But I'm leaving sonic booms running past the World Bank, so maybe relativity is a good thing.

My epiphany was triggered by the fallacy in this article, but it's just another one in a long series of pinpricks to my angst.

And now, everything is explained, or explainable. So, slowing down, take breath, take time to write some words, open the wine. Deep breathing.

Here goes.

The problem with THE AID WORLD, speaking broadly, is observed thusly: we keep doing it, and nothing much happens. In short, the aid budget is approved, carved up into tranches, and the slices and dices get scattered across the poverty-sphere like so much glitter. We sit back as happy church goers and do-gooders and believe we've done our religious duty. We wait for results.

Whatever the psychology of why we do it, what does happen is ... nothing much. The results are always short of expectations.

OK, so there are some very rare exceptions that we all talk about, but everyone in the business knows how rare they are because they are a household name. That's why we talk about them! I speak of mPesa of course, and ... well I don't actually know another in the last decade, but hey, that's what comments are for. Corrections please.

OK, so there are some very rare exceptions that we all talk about, but everyone in the business knows how rare they are because they are a household name. That's why we talk about them! I speak of mPesa of course, and ... well I don't actually know another in the last decade, but hey, that's what comments are for. Corrections please.

Fact is, most all aid is wasted. Most all government and private sector charity is mostly dead before it gets there, to that country far far away, and what little that does get there is stolen. Often, it is stolen in ways that tick ALL the boxes, and the beneficiaries will debate vociferously that it is not stolen at all, but I will say to you now - it's literally managed out of your hands, and out of the hands of its intended beneficiaries.

Yet we keep doing it. (So do they.) Why? So there are two serious questions here, being why it doesn't work, and why we keep doing it in the face of lifetimes of experience.

And finally it clicks for me: the market for aid is a Spence market in insufficient information. Which explains *everything* I just said, but now we need to walk through what this means. Because Spence is subtlety wrapped in a riddle, encrypted within a fairy tale.

In a Spence market, there is insufficient information, on both sides. This assumes a market where there is a nominal buyer and a nominal seller, but don't get too hung up on that. It's two people and they are trading something: graduates trading with employers, security providers selling to big scared corps, military contractors selling F35s to governments. In this case, there is a donor and a recipient.

The issue of insufficient information is symmetric -- neither side knows what is needed, nor what the other side wants. In effect, there is a vacuum of information. What happens with a vacuum? Of course, it is filled, by laws of physics. However what it is filled with is not information but "something else" being whatever is to hand.

The issue of insufficient information is symmetric -- neither side knows what is needed, nor what the other side wants. In effect, there is a vacuum of information. What happens with a vacuum? Of course, it is filled, by laws of physics. However what it is filled with is not information but "something else" being whatever is to hand.

Michael Spence postulated in his "Job Market Signalling" paper that what fills the vacuum of information insufficiency are signals. He was quite peculiar about what signals are: they were things that might say something, but actually they were not strong enough to be reliable. Importantly, signals could be misinterpreted to be "what I wanted to be told!"

Oops. We have a market where the information rushes in to fill the vacuum, but the because of the nature of this market, it isn't sufficiently confirming or disconfirming of the product as to generate a useful result. In essence, the signals are interpretable as confirming by the listener, when they may very well be the opposite: disconfirming.

Or, in other words, if we don't know what we're asking for, we shouldn't be surprised when our partner tells us what we'd like to hear. Ask your spouse about that one.

In such a market, Spence postulated that the signals can generate feedback loops which become reinforcing, over time and over cycles, even though they are not actually delivering information, or the information is irrelevant, or even wrong.

Now - AID. We want to do aid, it's kind of an inbuilt human reflex for good people, as well as a learnt behaviour, and one that generates positive feedback from our peers. So we take a swag of money down to our nearest poor country and hand it over.

Now - AID. We want to do aid, it's kind of an inbuilt human reflex for good people, as well as a learnt behaviour, and one that generates positive feedback from our peers. So we take a swag of money down to our nearest poor country and hand it over.

What does the recipient in our model do?

Whatever the recipient does with the money isn't relevant. What is relevant is what the recipient tells us. He tells us ... what we want to hear. He feeds us the signal. Because of the nature of the market, we can't tell, so we simply are incentivised to believe what he says. Which we do, probably because our motivation is as much about feeling good about ourselves as anything else.

I mean, it's not as if anyone has a good handle on this economic growth thing in the western world, so it would be a miracle if we actually could make it go better in the developed world.

But, leaving aside how we address the paucity of approaches, the result is: neither donor nor recipient *know* anything useful. But the donor is incentivised to invest, and praise the recipient's hard work. Recipient is incentivised to do whatever he is told to, and tell the donor that which he thinks the donor wishes to hear.

In such a market, the signal is misinterpreted, but the market is stable around the signal. Including the misinterpretation; Life goes on. Every aid cycle, the same thing happens, and nobody notices that there is no real tangible confirming information.

Which explains everything: this explains why extremely smart people go to these places and prepare big programmes that cost a *lot* of money. It also explains why the programmes never work, because the information from the recipient isn't precise or rich enough to actually develop a useful programme. It explains why huge numbers of people work on programmes even knowing in their honest moments they don't know what they are doing, and that the system doesn't work.

And it explains why the western aid movement does such terrible damage to these developing peoples -- because the developing peoples keep telling us it's good, in order to get the money. But the corrupting influence of the aid money is so evident on the ground it's not even funny.

It's utterly, viscerally the saddest thing I've ever seen; rich white people and poor africans, asians, latinos, locked in a deadly embrace of self-harm.

It's utterly, viscerally the saddest thing I've ever seen; rich white people and poor africans, asians, latinos, locked in a deadly embrace of self-harm.

But at least I now have a model to explain this to all those aid / NGOs / governments that haven't a clue. After rain, there can be a small ray of sunshine.

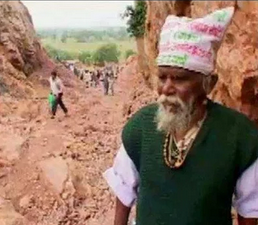

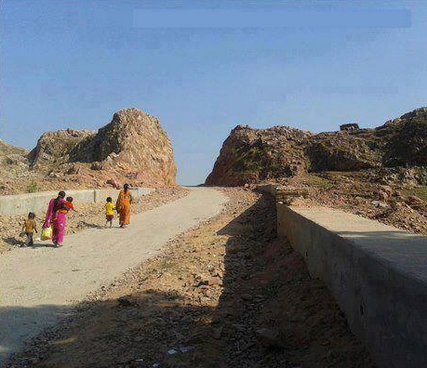

This post is dedicated to the man in the photos, who tore down a mountain. By himself. With no help from the west. (1, 2, 3, 4.)

March 10, 2015

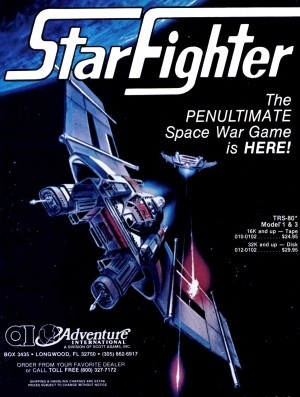

Finally, someone is facing up to the critical problem of our age: Starfighter

What is the critical problem of our age? Getting people back to productive work.

What is the critical problem of our age? Getting people back to productive work.

The economic statistics in the west are the worst in living memory, all the way back to the Great Depression. Not the official, manipulated political advertisements from the Bureau of Lies, Damn Lies & Statistics, but the anecdotes and wails of our friends and companions who are facing obscurity of unemployment or loss-of-soul with the big 5, no choice, nothing in between.

We -- in the aggregate -- have no understanding of how we got to here, what here is and how we're going to fix the issue.

I know one factor, the Spence observation that we live in an insufficient information age where employers cannot accurately predict employees, and employees likewise cannot see past plastic brand to the wholesomeness of their future career. The result is a deadly embrace of spiralling disquality.