September 28, 2010

Feel the dark side of Intellectual Property Rights. You know you want to....

The dark side of Intellectual Property is this: the structure of the market encourages theft, and more so than the more polite in society would predict. It's something that has really annoyed both sides of the debate; those who want to steal grumble about owners making it hard, while owners grumble that they need the help of their government for terrorising the first lot into financial dependency.

Two of the most abject victims of wikinomics are the newspaper and music industries. Since 2000, 72 American newspapers have folded. Circulation has fallen by a quarter since 2007. By some measures the music industry is doing even worse: 95% of all music downloads are illegal and the industry that brought the world Elvis and the Beatles is reviled by the young. Why buy newspapers when you can get up-to-the-minute news on the web? Why buy the latest Eminem CD when you can watch him on YouTube for free? Or, as a teenager might put it: what’s a CD?

Now, if it does that, if IP is structured that way, we can ask a number of searching questions. Was that what we intended? Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Can we improve it?

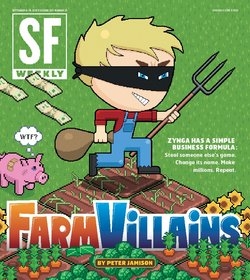

An interesting case of a company called Zynga (mentioned in last week's story) seems to make the case. First off, theft seems to be part & parcel of intellectual property:

In the latest SF Weekly cover story, multiple former employees of Zynga, speaking on condition that their names not be published so that they could discuss their work experiences candidly, tell us that studying and copying rivals' game concepts was business as usual. One senior employee who has since left the company describes a meeting where Zynga CEO and founder Mark Pincus said, "I don't fucking want innovation. You're not smarter than your competitor. Just copy what they do and do it until you get their numbers."

There's two ways of looking at this. Maybe Pincus has perfected a novel use of the perfect market hypothesis in innovation? Outstanding! In brief, the perfect market hypothesis as applied would say that the market has already acquired all the information, hence there is no point in trying to beat it, hence we should simply acquire the market.

Or maybe he has developed a new theory of creative destruction in innovation, following Schumpeter? It's certainly not my grandmother's definition of innovation, and some would call it by worse names (Guernica springs to mind, if I can bring in an IP link).

|

| The Creative Destruction Theory of Innovation |

On the other hand, the artists have a different take on the topic:

One of the more common complaints among former Zynga employees is about Pincus' distaste for original game design and indifference to his company's applications, beyond their ability to make money. "The biggest problem I had with him was that he didn't know or care about the games being good -- the bottom line was the only concern," a former game designer says. "While I'm all for games making money, I like to think there's some quality there."

Above, the "former game designer" suggests that his view of "goodness" should override the market's view, as expressed by the bottom line. The clear statement of his boss is the other way around.

Such a disdain for the message of the users is somewhat typical of fields of artistic endeavour where artists create their own shared, internal sense of goodness, and seek to avoid the market's view as insufficiently enlightening or overly opaque (etc). From where I sit, this is a view that artists can hold in a greenfield design where there simply isn't a market, and/or where the artist is also the investor.

But that latter point is troubling. Innovators are like artists, as a whole. One could suggest that innovators won't monetarise, because they'll be focussed on "goodness" and we might well be wasting our time supporting them to the extent of actually listening to them (I speak as an innovator, but prefer you not to mention it today). One could also suggest that they can't monetarise because that trap makes them perpetually too poor to invest.

What then happens if the innovatory process is really stacked in this direction? What happens if most innovators can't monetarise? How do we support a rationale whereby we as society should continue to support innovators with intellectual property rights at all? Why patents, brands, ideas, copyright, etc?

One answer is so they can recover at least something after it is appropriated:

One answer is so they can recover at least something after it is appropriated:

Another former employee recalls a meeting where Zynga workers discussed a strategy for copying a gangster game, Mob Wars, and creating Zynga's own Mafia Wars application. "I was around meetings where things like that were being discussed, and the ramifications of things like that were being discussed -- the fact that they'd probably be sued by the people who designed the game," he says. "And the thought was, 'Well, that's fine, we'll settle.' Our case wasn't really defensible." (Mob Wars' creator, David Maestri, proprietor of Psycho Monkey, did sue Zynga for copyright infringement. The case was settled for an undisclosed amount.)

So let's stop doing upfront licensing and sales of IPR. The point being that as long as the innovator keeps innovating, and product gets to market, it matters not to everyone else whether he's paid for it before or after its use. Everyone wins.

Just not the way we thought. Not what the brochure said. The goal of intellectual property rights then might not be to save the rights, but to lose them. And, the more you lose, the better, as the the better the theft, the more you can claim back.

(On the search for a good aporism here! Comments welcome.)

If that were so, if we were to assume IP theft as a goal of public policy, we'd be switching our emphasis to making IP easier to prove and recover in litigation. Registrations might deal with the first part (but are arguably too too cumbersome and expensive).

What deals with the second part? How do we improve the rate of recovery in IP litigation? By all accounts, the victim in any litigation is typically the small guy, so the innovator has it stacked against him or her there, too.

Posted by iang at September 28, 2010 09:41 PM | TrackBack> One of the more common complaints among former Zynga employees is about

> Pincus' distaste for original game design and indifference to his

> company's applications, beyond their ability to make money. "The

> biggest problem I had with him was that he didn't know or care about

> the games being good -- the bottom line was the only concern," a former

> game designer says. "While I'm all for games making money, I like to

> think there's some quality there."

This goes to one of the most fundamental, fateful characteristics of a market economy: the way the numbers work, is that they reflect what other people want, and are willing to pay for (and have the money to pay for.) It does not allow people to draw down goods and services, in exchange for doing what we think is right, or wrong, or for God or anything else.

Leave aside for the moment, the large fraction of market demand that is unearned, resulting from money creation. The remaining portion of the market does operate as intended-- as a system of exchange between principle parties. It's tied to what somebody else wants.

Tragically, you can make more money selling addictive drugs or any of 10000 harmful things. That's the state of humanity. A state of ignorance, really. Trying to resist the truth is futile. Basically, humanity is in the process of collective suicide, destroying its biosphere in a totalitarian suicide economy. Anything that changes this trend will have to be undemocratic, since people are manifestly, voting for the extinction option with their money as well as their votes.

Posted by: Todd at September 28, 2010 07:22 PM@ Todd,

"Basically, humanity is in the process of collective suicide destroying its biosphere in a totalitarian suicide economy."

I have been aware of this since the early 1980's (yup I'm long in the tooth ;)

I used to ask people the following question,

'Is growing the economy by the destruction of non renewable resources a good idea?'

Back then those of my age or younger said "definatly not" while those older (pre baby boomer) said "absolutly". At the time I put it down to generational differences in awareness and security.

However as time has gone on it's still a case that those under 25 think it's a bad idea whilst those over 30 think it's a good idea...

So it appears the older you get the more selfish you get, or is it the specter of your own mortality and impending retirment or redundancy scaring people into anything that keeps their personal gravy train rolling into their cessation of work and dependence on the interest and capital of past savings...

Posted by: Clive Robinson at October 10, 2010 12:53 PM