January 20, 2009

Selgin on the subtle competition between "official" and "alternative" currencies

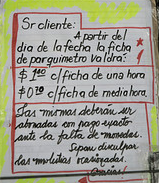

Argentina has run out of coins it seems, something that happens when your government thinks it knows how to run an economy better than the people, and it falls for the old commodity-coinage-price-inversion trick. (Last I heard, the same had happened in the USA, so don't laugh so hard....)

Why the shortage? Argentina's central bank blames it on "speculators," meaning everyone from ordinary citizens, who stockpile coins, to Maco, the private cash-transport company (think of Brinks) that repackages change gathered from bus companies to resell at an 8% premium. But those explanations ring false. "Black marketeering" would not exist if coins were easy to get in the first place. After all, Argentines could just as easily hoard razor blades or matchbooks. Yet there's no shortage of those. What's so special about coins?The answer is that coins are supplied by the government alone. "Put the federal government in charge of the Sahara desert," Milton Friedman said, "and in five years there'd be a sand shortage." If Argentina wants to end the coin shortage, it ought to give up its monopoly.

Crazy? Not if history is the guide. Over two centuries ago, Great Britain faced a coin shortage more severe than Argentina's -- so severe that it threatened to stop British industrialization in its tracks. People struggled to get coins for everyday use. The average worker was lucky to make 10 shillings a week, while the smallest banknotes were for 10 times as much. So the coin shortage even prevented factories from paying wages.

Like Argentina's government today, the British government wasn't able to end the shortage. Yet the shortage did end -- thanks to private-sector action. Fed up with the government's inaction, British firms started minting their own coins. Within a decade a score of private mints struck more coins than the Royal Mint had issued in half a century -- and better ones: heavier, more beautiful, and a lot harder to fake. Yet they were also less expensive, since private coiners sold their products at cost plus a modest markup, like other competitive firms, instead of charging the coins' face value, as governments like to do. Finally, when those who had accepted the private coins for payment went back to the issuer to redeem them, issuers offered to exchange their coins for central bank notes at no cost.

The blindingly obvious way to deal with this, for economists who've done any reading of the free banking literature, is to allow alternative currencies. The problem then arises that the Central Banks will resist this because of the threat to control. I was asked this question yesterday, and while I gave an answer, Prof. George Selgin's description is better. He outlines the path to "controlling" competing currencies in this WSJ post. It is subtle, and takes some getting used to.

If Argentina wants to end the shortage, it ought, not only to tolerate private coinage, but to sanction it. It can do so, while eliminating any risk that such coinage would be abused, through very simple legislation. It should allow any private firm to issue distinctly marked coins, perhaps subject to some minimal capital requirements, while making it clear that no one need ever accept any privately issued coins , even as change for purchases.Such a law may be all that's needed to solve the coin shortage, while also preventing anyone from forcing people to accept money they didn't trust. Anyone, that is, except the Central Bank of Argentina.

The subtle essence I highlight above is to create a range of slight benefits for the official currency, over freely competing alternatives. If ones goal for monetary policy is inflation control and a sound official unit of currency, then it isn't necessary to totally ban the alternatives, instead it is sufficient to make yours more attractive.

This can be done by having a few rules. One is the legal tender rule, which says ONLY that a debt that is offered for payment (proferred?) in the legal tender is considered to be paid. So, if I offer you $$$ and if you don't accept my $$$, and prefer the debt paid in bananas instead, the debt is legally acceptable as paid, in court.

This amounts to a very subtle and relatively small subsidy in favour of the official currency. It is enough to make it the favoured one. It is cheating, of course, because the Central Bank is not competing on a level playing field. Which is why it is important to ground this in monetary policy goals.

If your goal is to control the economy, then you won't permit this to happen at all, and your economy will suck, because of the Misean calculation problem. Indeed, banning private monies amounts to evidence that your goal is to control the economy, and as we know this is impossible, it is evidence of the government's ignorance of economics.

So the issue with alternative currencies is:

First, recognise that your monetary policy goal is your own sound currency, not control of the economy. Second, loosen the controls to open up the way for alternatives. Third, leave the official one on the pedestal for sufficient "official" purposes, using tricks like legal tender law.... Fourth, encourage the alternatives to reach places yours does not.

This way, the alternatives cannot knock it off the pedestal for the time being, but the alternatives fill the niches in the economy that the official unit cannot reach. This is true monetary policy; for the benefit of the people, not against them.

Posted by iang at January 20, 2009 10:06 AM | TrackBackThought you and your readers might be interested to know that Lawrence H. White who wrote "Free Banking in Britain" will be kicking off the Digital Money Forum in London this year.

Posted by: Dave Birch at January 25, 2009 05:39 PMWow! Prof White is one of my personal heroes, my copy of his book is full of my scribbled notes. When I was first writing my digital cash software, I "proved" digital cash assumptions using his models and mathematics.

WOW!

Posted by: Iang at January 25, 2009 05:52 PM