March 11, 2015

I'm so stupid - The market for aid is a Spence insufficient information market

I just figured it out, in a flash: Aid is Spencian.

I just figured it out, in a flash: Aid is Spencian.

3 years after my Kenyan adventure started, and I feel like I've got the intellectual dexterity of a slug. But I'm leaving sonic booms running past the World Bank, so maybe relativity is a good thing.

My epiphany was triggered by the fallacy in this article, but it's just another one in a long series of pinpricks to my angst.

And now, everything is explained, or explainable. So, slowing down, take breath, take time to write some words, open the wine. Deep breathing.

Here goes.

The problem with THE AID WORLD, speaking broadly, is observed thusly: we keep doing it, and nothing much happens. In short, the aid budget is approved, carved up into tranches, and the slices and dices get scattered across the poverty-sphere like so much glitter. We sit back as happy church goers and do-gooders and believe we've done our religious duty. We wait for results.

Whatever the psychology of why we do it, what does happen is ... nothing much. The results are always short of expectations.

OK, so there are some very rare exceptions that we all talk about, but everyone in the business knows how rare they are because they are a household name. That's why we talk about them! I speak of mPesa of course, and ... well I don't actually know another in the last decade, but hey, that's what comments are for. Corrections please.

OK, so there are some very rare exceptions that we all talk about, but everyone in the business knows how rare they are because they are a household name. That's why we talk about them! I speak of mPesa of course, and ... well I don't actually know another in the last decade, but hey, that's what comments are for. Corrections please.

Fact is, most all aid is wasted. Most all government and private sector charity is mostly dead before it gets there, to that country far far away, and what little that does get there is stolen. Often, it is stolen in ways that tick ALL the boxes, and the beneficiaries will debate vociferously that it is not stolen at all, but I will say to you now - it's literally managed out of your hands, and out of the hands of its intended beneficiaries.

Yet we keep doing it. (So do they.) Why? So there are two serious questions here, being why it doesn't work, and why we keep doing it in the face of lifetimes of experience.

And finally it clicks for me: the market for aid is a Spence market in insufficient information. Which explains *everything* I just said, but now we need to walk through what this means. Because Spence is subtlety wrapped in a riddle, encrypted within a fairy tale.

In a Spence market, there is insufficient information, on both sides. This assumes a market where there is a nominal buyer and a nominal seller, but don't get too hung up on that. It's two people and they are trading something: graduates trading with employers, security providers selling to big scared corps, military contractors selling F35s to governments. In this case, there is a donor and a recipient.

The issue of insufficient information is symmetric -- neither side knows what is needed, nor what the other side wants. In effect, there is a vacuum of information. What happens with a vacuum? Of course, it is filled, by laws of physics. However what it is filled with is not information but "something else" being whatever is to hand.

The issue of insufficient information is symmetric -- neither side knows what is needed, nor what the other side wants. In effect, there is a vacuum of information. What happens with a vacuum? Of course, it is filled, by laws of physics. However what it is filled with is not information but "something else" being whatever is to hand.

Michael Spence postulated in his "Job Market Signalling" paper that what fills the vacuum of information insufficiency are signals. He was quite peculiar about what signals are: they were things that might say something, but actually they were not strong enough to be reliable. Importantly, signals could be misinterpreted to be "what I wanted to be told!"

Oops. We have a market where the information rushes in to fill the vacuum, but the because of the nature of this market, it isn't sufficiently confirming or disconfirming of the product as to generate a useful result. In essence, the signals are interpretable as confirming by the listener, when they may very well be the opposite: disconfirming.

Or, in other words, if we don't know what we're asking for, we shouldn't be surprised when our partner tells us what we'd like to hear. Ask your spouse about that one.

In such a market, Spence postulated that the signals can generate feedback loops which become reinforcing, over time and over cycles, even though they are not actually delivering information, or the information is irrelevant, or even wrong.

Now - AID. We want to do aid, it's kind of an inbuilt human reflex for good people, as well as a learnt behaviour, and one that generates positive feedback from our peers. So we take a swag of money down to our nearest poor country and hand it over.

Now - AID. We want to do aid, it's kind of an inbuilt human reflex for good people, as well as a learnt behaviour, and one that generates positive feedback from our peers. So we take a swag of money down to our nearest poor country and hand it over.

What does the recipient in our model do?

Whatever the recipient does with the money isn't relevant. What is relevant is what the recipient tells us. He tells us ... what we want to hear. He feeds us the signal. Because of the nature of the market, we can't tell, so we simply are incentivised to believe what he says. Which we do, probably because our motivation is as much about feeling good about ourselves as anything else.

I mean, it's not as if anyone has a good handle on this economic growth thing in the western world, so it would be a miracle if we actually could make it go better in the developed world.

But, leaving aside how we address the paucity of approaches, the result is: neither donor nor recipient *know* anything useful. But the donor is incentivised to invest, and praise the recipient's hard work. Recipient is incentivised to do whatever he is told to, and tell the donor that which he thinks the donor wishes to hear.

In such a market, the signal is misinterpreted, but the market is stable around the signal. Including the misinterpretation; Life goes on. Every aid cycle, the same thing happens, and nobody notices that there is no real tangible confirming information.

Which explains everything: this explains why extremely smart people go to these places and prepare big programmes that cost a *lot* of money. It also explains why the programmes never work, because the information from the recipient isn't precise or rich enough to actually develop a useful programme. It explains why huge numbers of people work on programmes even knowing in their honest moments they don't know what they are doing, and that the system doesn't work.

And it explains why the western aid movement does such terrible damage to these developing peoples -- because the developing peoples keep telling us it's good, in order to get the money. But the corrupting influence of the aid money is so evident on the ground it's not even funny.

It's utterly, viscerally the saddest thing I've ever seen; rich white people and poor africans, asians, latinos, locked in a deadly embrace of self-harm.

It's utterly, viscerally the saddest thing I've ever seen; rich white people and poor africans, asians, latinos, locked in a deadly embrace of self-harm.

But at least I now have a model to explain this to all those aid / NGOs / governments that haven't a clue. After rain, there can be a small ray of sunshine.

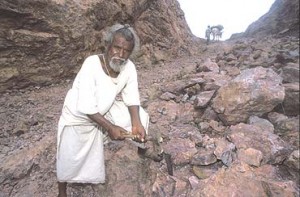

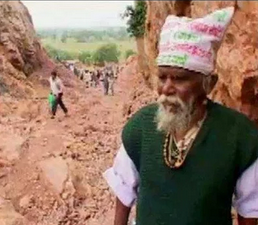

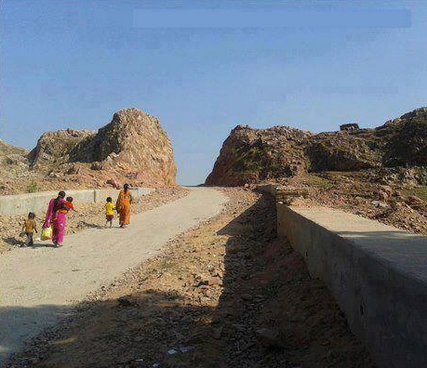

This post is dedicated to the man in the photos, who tore down a mountain. By himself. With no help from the west. (1, 2, 3, 4.)

Posted by iang at March 11, 2015 05:40 PMDid foreign aid really have anything to do with mPesa? Just a question.

Posted by: Olivier at March 13, 2015 01:51 PMYes, definitely -- DFID (the UK Department for International Development) provided the grants that financed the process to build the mPesa system.

My understanding is that the grant was for 1 million pounds. I'm not sure why this is not trumpeted more, it's a mine of information as to how to do things.

Click below to see wikipedia's take.

Posted by: Iang (mPesa History) at March 14, 2015 10:41 AMMan plants a tree every day for 37 years, grows a forest.

Posted by: Jadav Payang at August 20, 2017 05:19 PM