May 25, 2020

REA - some thoughts on relationship to TEA & computer science

In the light of the jolly good rave: "REA, Triple-Entry Accounting and Blockchain: Converging Paths to Shared Ledger Systems" by Ibañez et al, just out recently, I've been thinking of the relationship between TEA or triple entry accounting and the accounting-led analogue of REA or Resource-Entity-Agent.

From my tech point of view, and my prior ignorance as not actually knowing about it until recently, I see REA as this: an idealized view over the reality of trade, aka an abstraction as we like to say in the programming world.

Assuming it is what it blithely says it is (and no, I've not researched further), we can apply a characteristics analysis:

- each element is necessary,

- can be measured, and

- is highly orthogonal to the others.

- Also, the combination of the three describes a fact, one which can be material...

- indeed, try this as a test: can you find a material fact which doesn’t fit into the REA view?

Further, composing tuples of this form into sets should suffice to describe any wider trade, at least at an accounting & bookkeeping level. This all by way of saying that REA feels like the right atomic unit on which to propose a new accounting foundation - certainly from a Computer Science and especially a data perspective it feels right.

Further, composing tuples of this form into sets should suffice to describe any wider trade, at least at an accounting & bookkeeping level. This all by way of saying that REA feels like the right atomic unit on which to propose a new accounting foundation - certainly from a Computer Science and especially a data perspective it feels right.

If this were all that were required, then we could simply REAify all the things, and get back to counting our profits.

But, I feel that this is far from it. Indeed I suspect that we’re just looking at the tip of the iceberg, and as the accounting profession looks a bit like a titanic from some angles I can see room for caution and slow navigation.

There is more to how than meets the eye. Let’s take R for resource. How do we describe all the things? This turns out to be a hard problem.

We can describe all the One Type of Things with some degree of success - most countries have cracked the problem of tracking all the cars, give or take a few robberies and insurance frauds. We have less success in tracking all the houses - many countries have difficulty and that includes many OECD countries; just try buying a house in these countries and discover how much trust, paperwork and hope is involved.

Maybe we can’t do the big expensive things? But we also fail at the cheap plentiful things. We can’t track a tomato from farm to salad, notwithstanding the claims of a hundred blockchain startup wannabes.

My own work came up with a neat solution, if you could render the thing into a Ricardian contract! Might work for houses and cars but less likely for tomatoes. Still at least there’s something.

What about E for Event? It turns out that the event is only a useful event if all the relevant parties actually agree to it - and therein lies a difficulty. This turns REA from a data description problem to a protocol problem!

Notice the switch? And in this perspective we find that the modern world of data, accounting and databases is upset by what is now known as blockchain: we need a protocol to turn a proposal into an event, which is what blockchains claim to do.

In 1995-97 Gary and I did it via a specialist financial cryptography protocol called SOX - but we only did it for limited use cases: asset moves and asset trades (exchange). Fast forward to 2009 and bitcoin introduced smart contracts which allows the platform to generalise the event. This idea of user-level programming of the event found further development in systems like Corda, Ethereum, EOSIO, etc. It may sound glib - but the steps from spotting REA as an the event to programming it up as a shared fact represent quite some advances in computer science, and the first step might have been to know what the question was, precisely.

Finally A for Actors. I’ve left the hardest until last: a digitally reliable means of defining an actor remains elusive to us. There are many systems out there, but they all have limitations, some quite dramatic. Eg, it’s easy to do identity if you can constrain your users to a club, but that presupposes you already know identity, and it’s useless outside the club. Another eg: you could rely on ID Dox, but it only works if the person is honest enough not to show a dodgy ID, which isn’t a normal or acceptable assumption, neither in accounting nor in bars.

Back in the 1990s, the pseudonym emerged as a technical solution for the Internet - but failed at a society level. This problem hasn’t really been solved in a universal sense, much as some say it is.

In sum, I think, from my limited perspective as a computer scientist, REA is a good abstraction, even a great one, perhaps the right one. Perhaps I say that because we managed to build it albeit in narrow form: the Riccy for the Resource, TEA to agree the Event, and pseudonyms for actors.

But really - we were only at the start. We need more universal answers for each of these axes. Watch this space?

January 01, 2020

Thoughts on momentum accounting

Way back in the 1980s, Yuji Ijiri came up with the idea of momentum accounting, which he also called triple entry bookeeping. This is a distinct idea to the triple entry we typically talk about in our circles, and indeed pre-dates the work of Todd Boyle, Gary Howland and myself.

The collision in names was unfortunate and unintended, I only found out about Ijiri's idea when someone pointed me to it much later. Which leaves us and many others wondering - are they the same? Connected? Aligned? Unconnected? and other outrage...

I see a connection, so I'll try and draw it out.

As I understand it, Ijiri's third entry is a derivative of two successive accounting entries, making it like momentum in physics. Therefore, he suggests, we could in effect use this 'calculus' technique on accounting records to predict the future direction of activity.

A summary of what Yuji believes can be illustrated in the following analogy. The profits of a company are like a motor trip. Sometimes the car is driving forwards, sometimes backwards, and sometimes sitting still. The Balance sheet tells the precise location of the vehicle. The Income statement tells how fast the vehicle is traveling. The speed of the vehicle describes to investors information that can be used to estimate the future only as long as the vehicle travels the same speed. The question of whether the car is accelerating or decelerating can only be determined by using past information to estimate. What if the new triple-entry method allowed for the calculation of acceleration, or the momentum of the company, as Yuji defines it.

Everyone wants to know the future, indeed there are entire departments in companies and topics at business school just for that - using data to predict the future. Ijiri's is a very neat idea, but I have a doubt.

To be frank, I am not comfortable with the notion that you can measure momentum by doing a 'calculus' over accounting records. "These methods are complicated and not free from problems and errors. Yuji acknowledges that there are many fallacies in this procedure..." As his third entry is derivative information, I suspect that its conceptual value (use) is limited by fraud / deception.

This is to emphasise the Bill Black school of accounting rather than the Yuji Ijiri school. Because accounting records are used (relied upon) by many people for many things, once someone starts doing 'derivative' processing and relying upon those results, the opportunity for gaming that player’s outcomes rises.

This concern is analogous to say Enron pumping the results at the end of quarter, or the sales department cutting corners at end of month to 'make the numbers.' Momentum accounting would create a new measurement to game, like a Heisenbergian effect or Goodhart’s Law, as soon as you stress a controversial measurement it becomes useless for the task at hand. Computer scientists will also recognise a sense of GIGO here - garbage in, garbage out.

(I’m not enough of an accountant to think beyond that concern, and I haven’t read Ijiri’s books; I await like others the attention of serious accountants.)

Now, switching to the idea of cryptographic receipts, our triple entry. The goal is to make the accounting records so reliable, they can be the money. The notion that the record alone is strong enough to be the trade led us to say "the receipt is the transaction." This is what Gary and I built in 1995-96, and what Todd Boyle theorised about in the late 1990s; once the transaction has been rendered into a cryptographically sealed record, and shared amongst the three, it becomes the entries. It dominates other data, to use CS lingo, and therefore replaces it or leads it, whether it be other records or other systems like double entry.

Hence triple entry.

At a knowledge level, this leads to a new phenomena: "I know that what you see is what I see" as @gendal captured it. Now, there is a meta message here such that where you can merge the accounting system with the reality it accounts for - the receipt is the transaction, or the smart contract is the trade, if you are blockchain oriented - we improve the quality of the base layer to the point where it isn't a representation, it's the reality.

Entries become the foundational facts, rather than just representing other facts.

Back to momentum accounting, the point about fraud & gaming is that (IMHO) you will never be able to rely on it if both the momentum calculations are simply observations from which anyone can draw conclusions, and the underlying records are subject to error.

But combined, momentum accounting over the top of cryptographic receipts, the former might work. In a sense, this is to suggest that cryptographic receipts are necessary for momentum accounting, and this might be one of the reasons why Ijiri’s ideas never took off: layering observations over uncertainty sounds risky, and the market wasn't ready to take it on.

That's the relationship I see - with the newer blockchain generation systems as an accounting layer, we now have a factual base where momentum accounting might take off. (To see the how, look at the paper on AI & blockchain.)

Also see tweetstorm rendition for those who like that sort of thing.

July 25, 2018

Zooko buys Groceries...

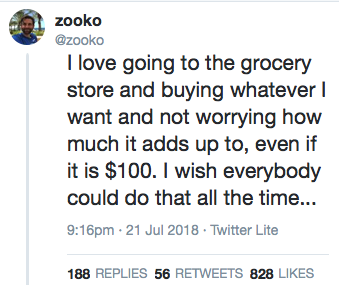

Zooko's tweet got me thinking, and it wasn't the flood of rejection he received.

I have been in that state, and I knew exactly what he meant. Been there, done that experience where you have to add each item, you have to shop for value, drop the things you want, and live on rice & beans.

I have been in that state, and I knew exactly what he meant. Been there, done that experience where you have to add each item, you have to shop for value, drop the things you want, and live on rice & beans.

Like billions of people.

Let me share an anecdote. Once upon a time I lived in Amsterdam. We had a sort of student or groupie house with some of us on the ground floor apartment and some of us on the next floor up. It was one of those places where the crazy landlady wanted crazy non-locals because we paid in cash and didn’t cause trouble.

My startup had just failed - in 1998 nobody wanted to issue hard cryptographically-protected secure instruments that could describe any money at all. Go figure. But those weren’t my worries then, what I was worried about then was … money.

Of the sort that purchased groceries, not the sort that the cypherpunks dreamed of and had but didn’t have. I would take the money to the grocery store and buy stuff. It was my job to do chilli con carne once in a while, like every few weeks. The money was someone else’s. Therefore my actual job was like taking a little money to the grocery store, buying 6 cans of tomatoes, 3 cans of beans, 1kg of minced meat, 3 chillies, onions and a lot of rice. Then cooking it and serving it.

That could feed about 5 adults for about 4 days.

That could feed about 5 adults for about 4 days.

For about 6 months I was in this state of poverty. It wasn’t the first time, nor the last, nor the worst - but it meant several things. I really had to watch the money. And wash clothes and iron shirts and cook chilli con carne and feed the group. I couldn’t make decisions because I couldn’t afford to make decisions. I couldn’t vary the menu because that was the cheapest.

Until I picked up a contract doing "requirements" for a local smart card money firm, I was stuck in this state. Every week or two, one of the guys from upstairs would invite me to the Bagel's 'n Beans (I think it was called) at the corner and we'd do breakfast in the sunshine and talk about financial cryptography and how to issue eCash and how to save the planet. Then he’d pay, and he’d go off to work because his startup hadn’t collapsed yet, and he still had a paycheck.

I was very conscious of the fact that if I hadn't had good friends, I'd be screwed. I was basically living for free while they were working their day jobs. It's hard to explain to those who have never faced it but there is a special hell for those who've had good paying jobs and then they get shut out. Of course, this happens to millions or billions, I'm not special.

The guy who liked Bagels was @zooko. Ever since that period I've tried to invite my poorer friends. Money didn’t matter, except when it did. Money was for living, not for making. Money was for doing, not for counting.

And I have thought a lot about what that time meant to me. It was that experience, and later experiences that led me to understand that the fabric of society isn't commerce, it isn't capitalism, it isn't profit and it very much isn't the dollar or the euro or the yen. The fabric of society is relationships. I didn't know it then, but I slowly found myself in the search for community. Not because I needed it, or not only, but because I thought that in community was the answer.

To the problem, and in 2008 I found myself again in deep poverty in the rich country of Austria. This time I had a job doing community auditing, which worked out at about €1 per hour, comfortably well below the poverty line, but alive. But, while we were building that community, we were watching the world’s financial community get into gridlock. Banks failing, countries on the verge, etc.

Since around 2000 - the dotcom crash - a lot of us had expected a real hard recession. It never happened, and we were mystified. Then in 2008 the answer was revealed. The man they called the magician, Alan Greenspan, had led bailout after bailout. Not of banks, but of the entire world system: the dotcom crash, 9/11, mutual funds scandal, fannie mae, something else... had all been rewarded with monstrous injections in liquidity. The banks or Alan Greenspan or someone had turned the entire western financial system into a bubble or a Ponzi or something.

And this last decade has been the mother of all bailouts - Quantitative Easing is nothing more than a gift to the financial system.

The problem I'm looking at then takes on a new aspect. What happens when the mother of all bubbles pops? When, not only can we not afford the groceries, but when there aren’t any grocery stores? We know something of this from Greece, from Puerto Rico, from Venezuela. How is it that people survive?

I knew it was relationship but I didn't know how. I knew people would save people, but how? My experiences in Amsterdam and Vienna and a few other episodes gave me no clear pattern - I knew that people saved people, but who, when and why in each circumstance?

Until, after a few more years skidding along the planetary row I found the how in Kenya - the chamas. It wasn’t that Kenyans were smarter than the westerners (they can be, and they’re definitely smarter than NGOs and aid workers who come to help) but it was clearer that there were two environmental factors that led them to work smarter, better, safer: poverty and corruption. It was out of these twin forces - I theorise - that they augmented their family and local trust lines into chamas.

Finding the how was pretty exciting. It was the lightbulb moment - the Eureka thing. Enough for me to quit my really safe and boring job in Australia and go to Kenya to build the first generation of chamapesa. It wasn’t because our technology spoke to chamas and chamas listened. It wasn’t because I loved Africa and the people were wonderful, it wasn’t because the business plan gasped an exponential curve to the moon. And it wasn’t because we could put a billion Africans on the blockchain, or a million blockchains on Africans.

It was because here was the solution, to everything I had not been able to work out before.

Like Zooko and a billion other people I’d spent many years in the grocery accounting trap. Like Zooko and millions of other people I’d lived the life of intelligent comfortable wealth and didn’t really care how much things cost.

Like Zooko and a billion other people I’d spent many years in the grocery accounting trap. Like Zooko and millions of other people I’d lived the life of intelligent comfortable wealth and didn’t really care how much things cost.

But like Zooko and a much smaller group of people, I've lived both those lives. That shock of poverty was burnt into our rich, educated privileged brains. And it matters. It drives us. It owns us, it changes us. I went to Kenya not for them but for all of us. To be nauseous, Chamapesa is our plan to get everyone to the grocery store so they don't care about the cost. And it is the rich west as well as the entrepreneurial Africans who'll need this.

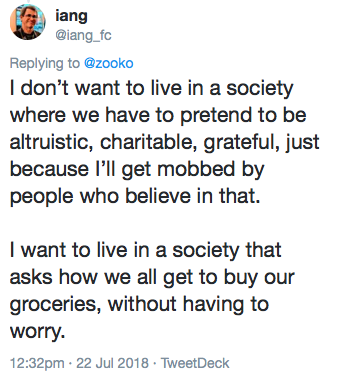

So when Zooko posts on his experiences, and gets attacked for lack of humility or lack of gratefulness, I understand the angst that these people have, but honestly, they’ve missed the point. Having lived on both sides of the tracks, it isn’t gratefulness or humility or charity that we find or care for or should exhibit, it is clarity of thought.

And this is where we separate from those in Silicon Valley or the NGO armies or the twitter social justice warriors or regulators or other oligopolists. They’ll never understand because those people have only lived on one side of the tracks.

You can't "fight poverty" when you work for a family wealth fund. You can't "save the poor" when you live in Silicon Valley and whiteboards & google are the extent of your knowledge. You can't blockchain your way to understanding. You can't "bank the unbanked" when your entire worldview is driven by the World Bank. You can't "give charitably" and expect that money to be spent wisely by those who receive charitably.

You get your degree in poverty by living it, not by going to University and studying IMF reports. So when Zooko exhibits his particular penchant for unfiltered thought, it is not going to fit in with people's polite ways of ignoring problems - humility, gratefulness, charity are all comforting techniques to avoid the problem.

The problem that Zooko is being daily reminded of and is highlighting to a de-sensitised readership is this: at some point poverty becomes a trap such that no amount of normal or routine activity can extract you out of it. Only a serious and literally life-changing intervention can fix that problem.

And here's where I can add: chamas are the routine & normal activity that can address the trap, because they were designed to do exactly that. Which is a solution available to some, and not to others. We had it in Amsterdam in some pre-formative sense. The long term outlook for those with access to these societal techniques is far better than those without. Working to a stronger society then is why I'm working on chamas, with Africans, and not on blockchain with silicon valley types.

I understand that the cost of that is I will be called all sorts of things. But, in this game, it is more important to have clarity of thought than to be liked.

June 29, 2017

SegWit and the dispersal of the transaction

Jimmy Nguyen criticises SegWit on the basis that it breaks the signature of a contract according to US law. This is a reasonable argument to make but it is also not a particularly relevant one. In practice, this only matters in the context of a particularly vicious and time-wasting case. You could argue that all of them are, and lawyers will argue on your dime that you have to get this right. But actually, for the most part, in court, lawyers don’t like to argue things that they know they are going to lose. The contract is signed, it’s just not signed in a particularly helpful fashion. For the most part, real courts and real judges know how to distinguish intent from technical signatures, so it would only be relevant where the law states that a particular contract must be signed in a particular way, and then we’ve got other problems. Yes, I know, UCC and all that, but let’s get back to the real world.

Jimmy Nguyen criticises SegWit on the basis that it breaks the signature of a contract according to US law. This is a reasonable argument to make but it is also not a particularly relevant one. In practice, this only matters in the context of a particularly vicious and time-wasting case. You could argue that all of them are, and lawyers will argue on your dime that you have to get this right. But actually, for the most part, in court, lawyers don’t like to argue things that they know they are going to lose. The contract is signed, it’s just not signed in a particularly helpful fashion. For the most part, real courts and real judges know how to distinguish intent from technical signatures, so it would only be relevant where the law states that a particular contract must be signed in a particular way, and then we’ve got other problems. Yes, I know, UCC and all that, but let’s get back to the real world.

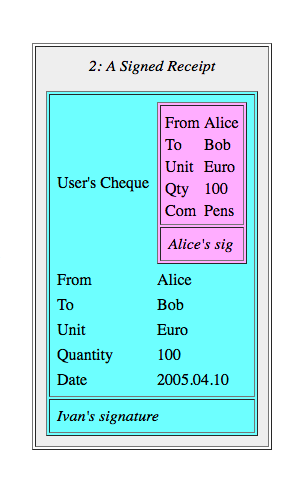

But there is another problem, and Nguyen’s post has triggered my thinking on it. Let’s examine this from the perspective of triple entry. When we (by this I mean to include Todd and Gary) were thinking of the problem, we isolated each transaction as being essentially one atomic element. Think of an entry in accounting terms. Or think of a record in database terms. However you think about it, it’s a list of horizontal elements that are standalone.

When we sign it using a private key, we take the signature and append it to the entry. By this means, the entry becomes stronger - it carries its authorisation - but it still retains its standalone property.

So, with the triple entry design in that old paper, we don’t actually cut anything out of the entry, we just make it stronger with an appended signature. You can think of it as is a strict superset of the old double entry and even the older single entry if you wanted to go that far. Which makes it compatible which is a nice property, we can extract double entry from triple entry and still use all the old software we’ve built over the last 500 years.

And, standalone means that Alice can talk to Bob about her transactions, and Bob can talk to Carol about his transaction without sharing any irrelevant or private information.

Now, Satoshi’s design for triple entry broke the atomicity of transactions for consensus purposes. But it is still possible to extract out the entries out of the UTXO, and they remain standalone because they carry their signature. This is especially important for say an SPV client, but it’s also important for any external application.

Like this: I’m flying to Shanghai next week on Blockchain Airlines, and I’ve got to submit expenses. I hand the expenses department my Bitcoin entries, sans signatures, and the clerk looks at them and realises they are not signed. See where this is going? Because, compliance, etc, the expenses department must now be a full node. Not SPV. It must now hold the entire blockchain and go searching for that transaction to make sure it’s in there - it’s real, it was expended. Because, compliance, because audit, because tax, because that’s what they do - check things.

Like this: I’m flying to Shanghai next week on Blockchain Airlines, and I’ve got to submit expenses. I hand the expenses department my Bitcoin entries, sans signatures, and the clerk looks at them and realises they are not signed. See where this is going? Because, compliance, etc, the expenses department must now be a full node. Not SPV. It must now hold the entire blockchain and go searching for that transaction to make sure it’s in there - it’s real, it was expended. Because, compliance, because audit, because tax, because that’s what they do - check things.

If Bitcoin is triple entry, this is making it a more expensive form of triple entry. We don’t need those costs, bearing in mind that these costs are replicated across the world - every user, every transaction, every expenses report, every accountant. For the cost of including a signature, an EC signature at that, the extra bytes gain us a LOT of strength, flexibility and cost savings.

(You could argue that we have to provide external data in the form of the public key. So whoever’s got the public key could also keep the sigs. This is theoretically true but is starting to get messy and I don’t want to analyse right now what that means for resource, privacy, efficiency.)

Some might argue that this causes more spread of Bitcoin, more fullnodes and more good - but that’s the broken window fallacy. We don’t go around breaking things to cause the economy to boom. A broken window is always a dead loss to society, although we need to constantly remind the government to stop breaking things to fix them. Likewise, we do not improve things by loading up the accounting departments of the world with additional costs. We’re trying to remove those costs, not load them up, honestly!

Then, but malleability! Yeah, that’s a nuisance. But the goal isn’t to fix malleability. The goal is to make the transactions more certain. Segwit hasn’t made transactions more certain if it has replaced one uncertainty with another uncertainty.

Today, I’m not going to compare one against the other - perhaps I don’t know enough, and perhaps others can do it better. Perhaps it is relatively better if all things are considered, but it’s not absolutely better, and for accounting, it looks worse.

Which does rather put the point on ones worldview. SegWit seems to retain the certainty but only as outlined above: when ones worldview is full nodes, Bitcoin is your hammer and your horizon. E.g., if you’re only thinking about validation, then signatures are only needed for validation. Nailed it.

But for everyone else? Everyone else, everyone outside the Bitcoin world is just as likely to simply decline as they are to add a full node capability. “We do not accept Bitcoin receipts, thanks very much.”

Or, if you insist on Bitcoin, you have to go over to this authority and get a signed attestation by them that the receipt data is indeed valid. They’ve got a full node. Authenticity as a service. Some will think “business opportunity!” whereas others will think “huh? Wasn’t avoiding a central authority the sort of thing we were trying to avoid?”

I don’t know what the size of the market for interop is, although I do know quite a few people who obsess about it and write long unpublished papers (daily reminder - come on guys, publish the damn things!). Personally I would not make that tradeoff. I’m probably biased tho, in the same way that Bitcoiners are biased: I like the idea of triple entries, in the same way that Bitcoiners like UTXO. I like the idea that we can rely on data, in the same way that Bitcoiners like the idea that they can rely on a bunch of miners.

I don’t know what the size of the market for interop is, although I do know quite a few people who obsess about it and write long unpublished papers (daily reminder - come on guys, publish the damn things!). Personally I would not make that tradeoff. I’m probably biased tho, in the same way that Bitcoiners are biased: I like the idea of triple entries, in the same way that Bitcoiners like UTXO. I like the idea that we can rely on data, in the same way that Bitcoiners like the idea that they can rely on a bunch of miners.

Now, one last caveat. I know that SegWit in all its forms is a political food fight. Or a war, depending your use of the language. I’m not into that - I keep away from it because to my mind war and food fights are a dead loss to society. I have no position one way or the other. The above is an accounting and contractual argument, albeit with political consequences. I’m interested to hear arguments that address the accounting issues here, and not at all interested in arguments based on “omg you’re a bad person and you’re taking money from my portfolio.”

I’ve little hope of that, but I thought I’d ask :-)

March 13, 2016

Elinor Ostrom's 8 Principles for Managing A Commmons

(Editor's note: Originally published at http://www.onthecommons.org/magazine/elinor-ostroms-8-principles-managing-commmons by Jay Walljasper in 2011)

Elinor Ostrom shared the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for her lifetime of scholarly work investigating how communities succeed or fail at managing common pool (finite) resources such as grazing land, forests and irrigation waters. On the Commons is co-sponsor of a Commons Festival at Augsburg College in Minneapolis October 7-8 where she will speak. (See accompanying sidebar for details.)

Ostrom, a political scientist at Indiana University, received the Nobel Prize for her research proving the importance of the commons around the world. Her work investigating how communities co-operate to share resources drives to the heart of debates today about resource use, the public sphere and the future of the planet. She is the first woman to be awarded the Nobel in Economics.

Ostrom’s achievement effectively answers popular theories about the "Tragedy of the Commons", which has been interpreted to mean that private property is the only means of protecting finite resources from ruin or depletion. She has documented in many places around the world how communities devise ways to govern the commons to assure its survival for their needs and future generations.

A classic example of this was her field research in a Swiss village where farmers tend private plots for crops but share a communal meadow to graze their cows. While this would appear a perfect model to prove the tragedy-of-the-commons theory, Ostrom discovered that in reality there were no problems with overgrazing. That is because of a common agreement among villagers that one is allowed to graze more cows on the meadow than they can care for over the winter—a rule that dates back to 1517. Ostrom has documented similar effective examples of "governing the commons" in her research in Kenya, Guatemala, Nepal, Turkey, and Los Angeles.

Based on her extensive work, Ostrom offers 8 principles for how commons can be governed sustainably and equitably in a community.

8 Principles for Managing a Commons

1. Define clear group boundaries.

1. Define clear group boundaries.

2. Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions.

3. Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules.

4. Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities.

5. Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior.

6. Use graduated sanctions for rule violators.

7. Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution.

8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

January 17, 2015

Gendal on blockchains -- what's the fuss? Could the blockchain change accounting?

Richard Gendal Brown of IBM comments on the blockchain, asking what's the fuss:

Cost? Trust? Something else? What's the killer-app for Block Chain Technology?Could decentralized ledgers change the face of accounting?

When I speak to people about decentralised ledgers, some of them are interested in the "distributed trust" aspects of the technology. But, more often, they bring up the question of cost.

This confused me at first. Think back to where this all started: with Bitcoin. Bitcoin is deliberately less efficient than a centralized ledger! Its design adds really difficult engineering constraints to what we already had. How could this technology possibly be cheaper than what we already have?

He then goes on to use some actual accounting to show that, amongst other things, cost isn't really what the discussion is about. By logic, he gets to a really interesting space, one that our readers will know well:

Sure - everybody still has a copy of the data locally... but the consensus system ensures that we know the local copy is the same as the copy everywhere else because it is the shared consensus system that is maintaining the ledger. And so we know we're producing our financial statements using the same facts as all the other participants in the industry.Does this mean we no longer need audit? No longer need reconciliations? Obviously not, but perhaps this approach is what is driving some of the interest in this space?

Right. To which I added, for the record:

To me, the magic in this space is what we sometimes flippantly call triple entry, which innovation is highlighted by the blockchain's success in mounting an independent currency over a shared ledger.

We all know how insubstantial internal ledger entries are, and how we can really only lean on them to the extent that we trust our internal processes (e.g. slightly germane is the events of 2007-08 leading to a popular view that accounting and audit have failed us).

On the other hand, we also see how solid the payment systems are. Whether bank- or govt- or private-run, payments generally work. When these multi-party activities do not work, all hell breaks loose, and people run, sometimes quite literally, to other systems.

When accounting ledgers break, we shrug. Triple entry takes us from the unreliable fantasy of the accounting entry to the hard concrete reality of the payment: the distributed ledger is as solid as a payment.

This doesn't replace double entry, nor does it replace classical payment systems. Rather it augments it by providing a way for parties to share certain transactions as if they were as solid as payments.

E.g., when RichardCo decides to place its capital at Barclays, it will no longer rely on its accounting systems alone to describe this situation, and neither will Barclays. Both of these parties will share a "receipt" that is cryptographically signed by some party that has mediated it (could be Barclays, could be the Bank of England, or it could be VirginMoney).

That's three parties, each holding a copy of the same receipt, hence the label triple entry. In the Bitcoin world, that middle intermediator is the blockchain, but single servers or replicated servers or small partner groups are equally applicable and in many cases better.

The receipt itself is strong because it is cryptographically authorised by the payer, and cryptographically signed off by the mediator (as a minimum). It represents such high class evidence that it is practically irrefutable in terms of the facts on record, and it is trivially automatable in audit terms.

Holding this entry is far more flexible than RichardCo and Barclays relying on their double entry systems because firstly you can build the double entry systems out of the collection of receipts any time you need them, and secondly, it is so strong that it can be used as evidence to create derivative claims. E.g., it's a set-up for securitization or loaning or other more advanced uses. And, it's a lot easier to audit because it is such solid evidence.

Back to bitcoin and its blockchain. This is the first successful experiment in a large scale triple entry issuance. In part, seeing what happens on the blockchainn generates excitement because we perceive an ability for any company to turn its stalled internal assets into contracts that are then dynamically mediated through cryptographic receipts.

Now, that contracting arrangement isn't there yet (see for example the conceptual tussle between smart contracts and Ricardian Contracts as mechanisms of issuance) but it will get there. Once I can issue all my accounted assets into a triple entry arrangement that others will instantly respect, finance will democratise so fiercely that if you're not seeing where it's going, the shock will probably take you down.

May 26, 2014

Why triple-entry is interesting: when accounting is the weapon of choice

Bill Black gave an interview last year on how the financial system has moved from robustness to criminogenia:

If you can steal with impunity, as soon as you devastate regulation, you devastate the ability to prosecute. And as soon as that happens, in our jargon, in criminology, you make it a criminogenic environment. It just means an environment where the incentives are so perverse that they are going to produce widespread crime. In this context, it is going to be widespread accounting control fraud. And we see how few ethical restraints remain in the most elite banks.You are looking at an underlying economic dynamic where fraud is a sure thing that will make people fabulously wealthy and where you select by your hiring, by your promotion, and by your firing for the ethically worst people at these firms that are committing the frauds.

No prizes for guessing he's talking about the financial system and the failure of the regulators to jail anyone, nor find any bank culpable, nor find any accounting firm that found any bank in trouble before it collapsed into the mercy of the public purse.

But where is the action? Where is the actual fraud taking place? This is the question that defies analysis and therefore allows the fraudsters to lay a merry trail of pointed fingers that curves around and joins itself. Here's the answer.

So in the financial sphere, we are mostly talking about accounting as the weapon of choice. And that is, where you overvalue assets, sometimes you undervalue liabilities. You create vast amounts of fictional income by making really bad loans if you are a lender. This makes you rich through modern executive compensation, and then it causes tremendous losses to the lender.

The first defence against this process is transparency. Which implies the robust availability of clear accounting records -- what really happened? Which is where triple-entry becomes much more interesting, and much more relevant.

In the old days, accounting was the domain of intra-firm transactions. Double entry enabled the growth of the business empire because internal errors could be eliminated by means of the double-links between separate books; clearly, money had to be either in one place or another, it couldn't slip between the cracks any more, so we didn't need to worry so much about external agents deliberately dropping a few entries.

Beyond the firm, it was caveat emptor. Which the world muddled along with for around 700 years until the development of electronic transactions. At this point of evolution from paper to electronic, we lost the transparency of the black & white, and we also lost the brake of inefficiency in transactions between firms. That which was on paper was evidence and accountable to an entire culture called accountants; that which was electronic was opaque except to a new generation of digital adepts.

Say hello to Nick Leeson, say good bye to Barings Bank. The fraud that was possible now exploded beyond imagination.

Triple-entry addresses this issue by adding cryptography to the accounting entry. In effect it locks the transaction into a single electronic record that is shared with three parties: the sender, the receiver and a third party to hold & adjudicate. Crypto makes it easy for them to hold the same entry, the third parties makes it easy to force the two interested agents not to play games.

You can see this concept with Bitcoin, which I suggest is a triple-entry system, albeit not one I envisaged. The transaction is held by the sender and the recipient of the currency, and the distributed blockchain plays the part of the third party.

Why is this governance arrangement a step forward? Look at say money laundering. Consider how you would launder funds through bitcoin, a fear claimed by the various government agencies. Simple, send your ill-gotten gains to some exchanger, push the resultant bitcoin around a bit, then cash out at another exchanger.

Simple, except every record is now locked into the blockchain -- the third party. Because it is cryptographic, it is now a record that an investigator can trace through and follow. You cannot hide, you cannot dive into the software system and fudge the numbers, you cannot change the records.

Triple-entry systems such as Bitcoin are so laughably transparent that only the stupidest money launderer would go there, and would therefore eliminate himself before long. It is fair to say that triple-entry is practically immunised against ML, and the question is not what to do about it in say Bitcoin, but why aren't the other systems adopting that technique?

And as for money laundering, so goes every other transaction. Transparency using triple-entry concepts has now addressed the chaos of inter-company financial relationships and restored it to a sensible accountable and governable framework. That which double-entry did for intra-company, triple-entry does for the financial system.

Of course, triple-entry does not solve everything. It's just a brick, we still need mortar of systems, the statics of dispute resolution, plans, bricklayers and all the other components. It doesn't solve the ethics failure in the financial system, it doesn't bring the fraudsters to jail.

And, it will take a long time before this idea of cryptographically sealed receipts seeps its way slowly into society. Once it gets hold, it is probably unstoppable because companies that show accounts solidified by triple-entry will eventually be rewarded by cheaper cost of capital. But that might take a decade or three.

________

H/t to zerohedge for this article of last year.

May 07, 2014

No Accounting Skills? No Moral Reckoning

While we're on the accounting theme (and why it matters for cryptocurrencies), this is a great article:

No Accounting Skills? No Moral Reckoning

By JACOB SOLL APRIL 27, 2014

SOMETIMES it seems as if our lives are dominated by financial crises and failed reforms. But how much do Americans even understand about finance? Few of us can do basic accounting and fewer still know what a balance sheet is. If we are going to get to the point where we can have a serious debate about financial accountability, we first need to learn some essentials.

The German economic thinker Max Weber believed that for capitalism to work, average people needed to know how to do double-entry bookkeeping. This is not simply because this type of accounting makes it possible to calculate profit and capital by balancing debits and credits in parallel columns; it is also because good books are “balanced” in a moral sense. They are the very source of accountability, a word that in fact derives its origin from the word “accounting.”

In Renaissance Italy, merchants and property owners used accounting not only for their businesses but to make a moral reckoning with God, their cities, their countries and their families. The famous Italian merchant Francesco Datini wrote “In the Name of God and Profit” in his ledger books. Merchants like Datini (and later Benjamin Franklin) kept moral account books, too, tallying their sins and good acts the way they tallied income and expenditure.

One of the less sexy and thus forgotten facts about the Italian Renaissance is that it depended highly on a population fluent in accounting. At any given time in the 1400s, 4,000 to 5,000 of Florence’s 120,000 inhabitants attended accounting schools, and there is ample archival evidence of even lowly workers keeping accounts.

This was the world in which Cosimo de’ Medici and other Italians came to dominate European banking. It was understood that all landowners and professionals would know and practice basic accounting. Cosimo de’ Medici himself did yearly audits of the books of all his bank branches; he also personally kept the accounts for his household. This was typical in a world where everyone from farmers and apothecaries to merchants — even Niccolò Machiavelli — knew double-entry accounting. It was also useful in political office in republican Florence, where government required a certain amount of transparency.

If we want to know how to make our own country and companies more accountable, we would do well to study the Dutch. In 1602, they invented modern capitalism with the foundation of the first publicly traded company — the Dutch East India Company — and the first official stock market in Amsterdam. But it was through an older and well-maintained culture of accountability that they kept these institutions stable for a century. The spread of double-entry accounting to the Netherlands during the early 1500s made the country the center of accounting education, world trade and early capitalism. Well-accounted-for provincial tax returns allowed the Dutch to float bonds at dependable 4 percent interest rates. The Dutch trusted their managers to know how to keep good books and make regular interest payments, while paying off state debt.

Every level of Dutch society practiced double-entry accounting — from prostitutes to scholars, merchants and even the Stadholder, Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange. Painters regularly depicted merchants keeping their books; Quentin Metsys’ “The Money Changers” (circa 1549) showed that even skilled accountants could be fraudulent. In other words, the advantages and pitfalls of accounting were at the fore of public consciousness.

Not only did the Dutch have basic financial management skills, they were also acutely aware of the concept of balanced books, audits and reckonings. They had to be. If local water board administrators kept bad books, the Dutch dyke and canal system would not be well maintained, and the country risked catastrophic flooding.

This desire for accountability was what pushed the Dutch to reform their financial system when it began to collapse under the weight of fraud. The first shareholder revolt happened in 1622, among Dutch East India Company investors who complained that the company account books had been “smeared with bacon” so that they might be “eaten by dogs.” The investors demanded a “reeckeninge,” a proper financial audit.

While the state did not allow the Dutch East India Company’s books to be audited in public, Prince Maurice did do a serious internal audit, and Dutch burghers were satisfied with both company and state accountability. A cultural ideal was set. For the next century, it became common practice for public administrators to have portraits of themselves painted with their account books — sometimes with real calculations in them — open, for all to see.

These historical examples point the way toward achievable solutions to our own crises. Over the past half century, people have stopped learning double-entry bookkeeping — so much so that few know what it means — leaving it instead to specialists and computerized banking. If we want stable, sustainable capitalism, a good place to start would be to make double-entry accounting and basic finance part of the curriculum in high school, as they were in Renaissance Florence and Amsterdam.

A population well-versed in double-entry accounting will not immediately solve our complex financial problems, but it would allow average citizens to understand the nuts and bolts of finance: balance sheets, mortgage interest, depreciation and long-term risk. It would also give them a clearer sense of what financial accountability really means and of how to ask for and assess audits. The explosion of data-driven journalism should also include a subset of reporters with training in accounting so that they can do a better job of explaining its central role in our economy and financial crises.

Without a society trained in accountability, one thing is certain: There will be more reckonings to come.

Jacob Soll, a professor of history and accounting at the University of Southern California, is the author, most recently, of “The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations.”

A version of this article appears in print on 04/28/2014, on page A21 of the NewYork edition with the headline: No Accounting Skills? No Moral Reckoning.

A triple-entry explanation for a minimum viable Blockchain

It's an article of faith that accounting is at the core of cryptocurrencies. Here's a nice story along those lines h/t to Graeme:

Ilya Grigorik provides a ground-up technologists' description of Bitcoin called "The Minimum Viable Blockchain." He starts at bartering, goes through triple-entry and the replacement of the intermediary with the blockchain, and then on to explain how all the perverse features strengthen the blockchain. It's interesting to see how others see the nexus between triple-entry and bitcoin, and I think it is going to be one of future historian's puzzles to figure out how it all relates.

Both Bob and Alice have known each other for a while, but to ensure that both live up to their promise (well, mostly Alice), they agree to get their transaction "notarized" by their friend Chuck.They make three copies (one for each party) of the above transaction receipt indicating that Bob gave Alice a "Red stamp". Both Bob and Alice can use their receipts to keep account of their trade(s), and Chuck stores his copy as evidence of the transaction. Simple setup but also one with a number of great properties:

- Chuck can authenticate both Alice and Bob to ensure that a malicious party is not attempting to fake a transaction without their knowledge.

- The presence of the receipt in Chuck's books is proof of the transaction. If Alice claims the transaction never took place then Bob can go to Chuck and ask for his receipt to disprove Alice's claim.

- The absence of the receipt in Chuck's books is proof that the transaction never took place. Neither Alice nor Bob can fake a transaction. They may be able to fake their copy of the receipt and claim that the other party is lying, but once again, they can go to Chuck and check his books.

- Neither Alice nor Bob can tamper with an existing transaction. If either of them does, they can go to Chuck and verify their copies against the one stored in his books.

What we have above is an implementation of "triple-entry bookkeeping", which is simple to implement and offers good protection for both participants. Except, of course you've already spotted the weakness, right? We've placed a lot of trust in an intermediary. If Chuck decides to collude with either party, then the entire system falls apart.

Grigorik then uses public key cryptography to ensure that the receipt becomes evidence that is reliable for all parties; which is how I built it, and I'm pretty sure that was what was intended by Todd Boyle.

However he walks a different path and uses the signed receipts as a way to drop the intermediary and have Alice and Bob keep separate, independent ledgers. I'd say this is more a means to an end, as Grigorik is trying to explain Bitcoin, and the central tenant of that cryptocurrency was the famous elimination of a centralised intermediary.

Moral of the story? Be (very) careful about your choice of the intermediary!

I don't have time right now to get into the rest of the article, but so far it does seem like a very good engineer's description. Well worth a read to sort your head out when it comes to all the 'extra' bits in the blockchain form of cryptocurrencies.

September 19, 2013

Research on Trust -- the numbers matter

Many systems are built on existing trust relationships, and understanding these is often key to their long term success or failure. For example, the turmoil between OpenPGP and x509/PKI can often be explained by reference to their trust assumptions, by comparing the web-of-trust model (trust each other) to the hierarchical CA model (trust mozilla/microsoft/google...).

In informal money systems such as LETS, barter circles and community currencies, it has often seemed to me that these things work well, or would work well, if they could leverage local trust relationships. But there is a limit.

To express that limit, I used to say that LETS would work well up to maybe 100 people. Beyond that number, fraud will start to undermine the system. To put a finer point on it, I claimed that beyond 1000 people, any system will require an FC approach of some form or other.

Now comes some research that confirms some sense of this intuition, below. I'm not commenting directly on it as yet, because I haven't the time to do more than post it. And I haven't read the paper...

'Money reduces trust' in small groups, study shows

By Melissa Hogenboom Science reporter, BBC News

People were more generous when there was no economic incentive

A new study sheds light on how money affects human behaviour.

Exchanging goods for currency is an age old trusted system for trade. In large groups it fosters co-operation as each party has a measurable payoff.

But within small groups a team found that introducing an incentive makes people less likely to share than they did before. In essence, even an artificial currency reduced their natural generosity.

The study is published in journal PNAS.

When money becomes involved, group dynamics have been known to change. Scientists have now found that even tokens with no monetary value completely changed the way in which people helped each other.

Gabriele Camera of Chapman University, US, who led the study, said that he wanted to investigate co-operation in large societies of strangers, where it is less likely for individuals to help others than in tight-knit communities.

The team devised an experiment where subjects in small and large groups had the option to give gifts in exchange for tokens.

The study

- Participants of between two to 32 individuals were able to help anonymous counterparts by giving them a gift, based solely on trust that the good deed would be returned by another stranger in the future

- In this setting small groups were more likely to help each other than the larger groups

- In the next setting, a token was added as an incentive to exchange goods. The token had no cash value

- Larger groups were more likely to help each other when tokens had been added, but the previous generosity of smaller groups suffered

Social cost

They found that there was a social cost to introducing this incentive. When all tokens were "spent", a potential gift-giver was less likely to help than they had been in a setting where tokens had not yet been introduced.

The same effect was found in smaller groups, who were less generous when there was the option of receiving a token.

"Subjects basically latched on to monetary exchange, and stopped helping unless they received immediate compensation in a form of an intrinsically worthless object [a token].

"Using money does help large societies to achieve larger levels of co-operation than smaller societies, but it does so at a cost of displacing normal of voluntary help that is the bread and butter of smaller societies, in which everyone knows each other," said Prof Camera.

But he said that this negative result was not found in larger anonymous groups of 32, instead co-operation increased with the use of tokens.

"This is exciting because we introduced something that adds nothing to the economy, but it helped participants converge on a behaviour that is more trustworthy."

He added that the study reflected monetary exchange in daily life: "Global interaction expands the set of trade opportunities, but it dilutes the level of information about others' past behaviour. In this sense, one can view tokens in our experiment as a parable for global monetary exchange."

'Self interest'

Sam Bowles, of the Santa Fe Institute, US, who was not involved with the study, specialises in evolutionary co-operation.

He commented that co-operation among self-interested people will always occur on a vast scale when "helping another" consists of exchanging a commodity that can be bought or sold with tokens, for example a shirt.

"The really interesting finding in the study is that tokens change the behavioural foundations of co-operation, from generosity in the absence of the tokens, to self-interest when tokens are present."

"It's striking that once tokens become available, people generally do not help others except in return for a token."

He told BBC news that it was evidence for an already observed phenomenon called "motivational crowding out, where paying an individual to do a task which they had already planned to do free of charge, could lead people to do this less".

However, Prof Bowles said that "most of the goods and services that we need that make our lives possible and beautiful are not like shirts".

"For these things, exchanging tokens could never work, which is why humans would never have become the co-operative species we are unless we had developed ethical and other regarding preferences."

July 17, 2012

Auditors All Fall Down; PFGBest and MF Global Frauds Reveal Weak Watchdogs

Without much comment, from Francine McKenna:

Auditors All Fall Down; PFGBest and MF Global Frauds Reveal Weak Watchdogs

[snip]

The made-for-TV drama is instead unfolding in Cedar Falls, Iowa and Chicago where, in “truth is stranger than fiction” style, PFGBest’s Russell Wasendorf Sr. says he used his “blunt authority” as sole owner and CEO to falsify bank statements sent to regulators for twenty years using Photoshop, Excel, scanners and laser printers.

Instead of MF Global’s world-renowned auditor PwC, we’ve got a one-woman show, Jeannie Veraja-Snelling, signing the audit opinion accompanying the financial statements for PFGBest. Not that there’s much less apparent incompetence when a global firm like PwC misses increased risk and deteriorating controls at MF Global and signs off on a clean annual audit opinion as recently as March 31, 2011, seven months before MF Global was forced into bankruptcy. PwC also signed off on a 10-Q review at the end of June, and a bond issue in August of 2011.

Wasendorf’s suicide note said that he duped his first-response regulator, the National Futures Association, by intercepting its request for confirmation of his bank balances, including funds segregated and safeguarded for customers, by using a P.O. Box he set up in the name of US Bank. He simply wrote whatever he wanted on those confirmation requests and signed in the name of the bank. His doctored banks statements with matching figures were sent along with the confirmation request back to the regulator.

“I was forced into a difficult decision: Should I go out of business or cheat?” he wrote. “I guess my ego was too big to admit failure. So I cheated,” his suicide note said.

Regulators, auditors and internal controls can not prevent a psychopath from lying, cheating and stealing to perpetuate a myth and sustain a lavish lifestyle, but they can and should detect the fraud much sooner if not immediately.

Wasendorf’s admission does not explain how he also duped the independent auditor. One of the cornerstones of an independent audit is an independent confirmation of bank balances. PFGBest’s auditor was either duped for twenty years or complicit in the fraud. Neither conclusion is a good one for her. Auditors are forbidden to use company personnel to obtain or process bank balance confirmations. Of course, that hasn’t prevented auditors from falling down on this critical part of their job anyway, leading recently to some of the biggest and most notorious fraud cases in years.

Deloitte’s audit client Parmalat gave that firm falsified bank confirmations. Deloitte’s Milan firm and its international coordinating firm eventually settled the 2003 case with Parmalat bondholders and shareholders for almost $200 million total. Price Waterhouse India partners are still facing criminal charges and the firm is being sued by its former audit client Mahindra Satyam for the fraud revealed by Satyam’s CEO who admitted to falsifying $1 billion in bank balances. Price Waterhouse India paid fines to the SEC, PCAOB, and settled with shareholders. Regulators said Price Waterhouse India’s audits were negligent because they failed to obtain confirmations of bank balances directly from banks and instead accepted management’s representations without independent verification. Several of the current Chinese frauds allege bank confirmation fraud, including accusations of collusion with executives by bank officials and negligence by auditors Deloitte China and others.

What’s even more troubling to me is PFGBest’s auditor, and many others who audit only SEC-registered broker-dealers, may be breaking laws as well as being negligent in their public duty to the capital markets.

(Big Snip)

On that latter, read the article for detail...

August 07, 2011

Regulating the future financial system - the double-entry headache needs a triple-entry aspirin

How to cope with a financial system that looks like it's about to collapse every time bad news turns up? This is an issue that is causing a few headaches amongst the regulators. Here's some musings from Chris Skinner over a paper from the Financial Stability gurus at the Bank of England:

Third, the paper argues for policies that create much greater transparency in the system.This means that the committees worldwide will begin “collecting systematically much greater amounts of data on evolving financial network structure, potentially in close to real time. For example, the introduction of the Office of Financial Research (OFR) under the Dodd-Frank Act will nudge the United States in this direction.

“This data revolution potentially brings at least two benefits.

“First, it ought to provide the authorities with data to calibrate and parameterise the sort of network framework developed here. An empirical mapping of the true network structure should allow for better identification of potential financial tipping points and cliff edges across the financial system. It could thus provide a sounder, quantitative basis for judging remedial policy actions to avoid these cliff edges.

“Second, more publicly available data on network structures may affect the behaviour of financial institutions in the network. Armed with greater information on counterparty risk, banks may feel less need to hoard liquidity following a disturbance.”

Yup. Real time data collection will be there in the foundation of future finance.

But have a care: you can't use the systems you have now. That's because if you layer regulation over policy over predictions over datamining over banking over securitization over transaction systems … all layered over clunky old 14th century double entry … the whole system will come crashing down like the WTC when someone flies a big can of gas into it.

The reason? Double entry is a fine tool at the intra-corporate level. Indeed, it was material in the rise of the modern corporation form, in the fine tradition of the Italian city states, longitudinal contractual obligations and open employment. But, double entry isn't designed to cope with the transactional load of of inter-company globalised finance. Once we go outside the corporation, the inverted pyramid gets too big, too heavy, and the forces crush down on the apex.

It can't do it. Triple entry can. That's because it is cryptographically solid, so it can survive the rigours of those concentrated forces at the inverted apex. That doesn't solve the nightmare scenarios like securitization spaghetti loans, but it does mean that when they ultimately unravel and collapse, we can track and allocate them.

Message to the regulators: if you want your pyramid to last, start with triple entry.

PS: did the paper really say "More taxes and levies on banks to ensure that the system can survive future shocks;" … seriously? Do people really believe that Tobin tax nonsense?

June 13, 2011

Is BitCoin a triple entry system?

James Donald recently gave me a foil on which to ask this interesting question. Although it took me a while to sort the wheat from the chaff, I'm finally getting to grips with the architecture.

On 13/06/11 12:56 PM, James A. Donald wrote:

> On 2011-06-12 8:57 AM, Ian G wrote:

> > I wrote a paper about John Levine's observation of low knowledge, way

> > back in 2000, called "Financial Cryptography in 7 Layers." The sort of

> > unstated thesis of this paper was that in order to understand this area

> > you had to become very multi-discipline, you had to understand up to 7

> > general areas. And that made it very hard, because most of the digital

> > cash startups lacked some of the disciplines.

>

> One of the layers you mention is accounting.

Yes, so back to crypto, or at least financial cryptography.

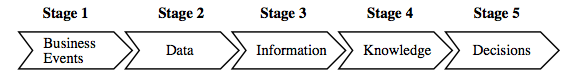

The accounting layer in a money system implemented in financial cryptography is responsible for reliably [1] holding and reporting the numbers for every transaction and producing an overall balance sheet of an issue.

It is in this that BitCoin may have its greatest impact -- it may have shown the first successful widescale test of triple entry [2].

Triple entry is a simple idea, albeit revolutionary to accounting. A triple entry transaction is a 3 party one, in which Alice pays Bob and Ivan intermediates. Each holds the transaction, making for triple copies.

To make a transaction, Alice signs over a payment instruction to Bob with her public-key-based signature [3]. Ivan the issuer then packages the payment request into a receipt, and that receipt becomes the transaction.

This transaction is digitally signed by multiple parties, including at least one independent party [4]. It then becomes a powerful evidence of the transaction [5].

The final receipt *is the entry*. Then, the *collection of signed receipts* becomes the accounts, in accounting terms. Which collection replaces ones system of double entry bookkeeping, because the single digitally signed receipt is a better evidence than the two entries that make up the transaction, and the collection of signed receipts is a better record than the entire chart of accounts [6].

A slight diversion to classical bookkeeping, as replacing double entry bookkeeping is a revolutionary idea. Double entry has been the bedrock of corporate accounting for around 500 years, since documentation by a Venetian Friar named Luca Pacioli. The reason is important, very important, and may resonate with cryptographers, so let's digress to there.

A slight diversion to classical bookkeeping, as replacing double entry bookkeeping is a revolutionary idea. Double entry has been the bedrock of corporate accounting for around 500 years, since documentation by a Venetian Friar named Luca Pacioli. The reason is important, very important, and may resonate with cryptographers, so let's digress to there.

Double entry achieves the remarkable trick of separating out mishaps from frauds. The problem with single entry (what people do when making lists of numbers and adding them up) is that the person can leave off a number, and no-one is the wiser [7]. We can't show the person as either a bad bookkeeper or as a fraudulent bookkeeper. This achilles heel of primitive accounting meant that the bookkeeping limited the business to the size with which it could maintain honest bookkeepers.

Where, honest bookkeepers equals family members. All others, typically, stole the boss's money. (Family members did too, but at least for the good of the family.) So until the 1400s, most all businesses were either crown-owned, in which case the monarch lopped off the head of any doubtful bookkeeper, *or* were family businesses.

The widespread adoption of double-entry through the Italian trading ports led to the growth of business beyond the limits of family. Double entry therefore was the keystone to the enterprise, it was what created the explosion of trading power of the city states in now-Italy [8].

Back to triple entry. The digitally signed receipt dominates the two entries of double entry because it is exportable, independently verifiable, and far easier for computers to work with. Double entry requires a single site to verify presence and preserve resiliance, the signed receipt does not.

There is only one area where a signed receipt falls short of complete evidence and that is when a digital piece of evidence can be lost. For this reason, all three of Alice, Bob and Ivan keep hold of a copy. All three combined have the incentive to preserve it; the three will police each other.

Back to BitCoin. BitCoin achieves the issuer part by creating a distributed and published database over clients that conspire to record the transactions reliably. The idea of publishing the repository to make it honest was initially explored in Todd Boyle's netledger design.

We each independently converged on the concept of triple entry. I believe that is because it is the optimal way to make digital value work on the net; even when Nakomoto set such hard requirements as no centralised issuer, he still seems to have ended up at the same point: Alice, Bob and something I'll call Ivan-Borg holding single, replicated copies of the cryptographically sealed transaction.

With that foundation, we can trade.

> Recall that in 2005

> November, it became widely known that toxic assets were toxic.

In 2005, the SEC looked at my triple entry implementation, and....

> From late in 2005 to late in 2007, it was widely known that major

> financial institutions were walking dead, and yet strangely they

> continued to walk, though this took increasingly creative changes of the

> rules.

...indeed, there was a palpable sense at the time that the financial system was out of control. They were looking at this thing with worried eyes.

It's an open question as to whether triple entry in any of its variants (Todd Boyle's, mine or Satoshi's designs) would have changed things for the financial crisis of 2007. I think the answer is; it was way too late to effect it. But, it wouldn't have hurt, and with other things added in [9], the sum would have changed things, assuming widespread implementation.

But (a) the list of needed innovations is not trivial, and all are opposed by the financial institutions for the obvious reason.

Also, (b) it has to be said that at the bottom of the financial crisis is securitization, which changes everything about finance [10]. And I do mean everything. Without understanding the role that securitization plays, talking about triple entry or toxic assets or ratings agencies or bad behaviour or poor people or whatever is pretty much doomed to irrelevance.

Which is how they like it!

> Today in 2011, there is still no audit that acknowledges that toxic

> assets were and are toxic.

This one winds all the way to [11] ...

> While doubtless a good monetary system should embrace all these aspects

> of knowledge, our existing monetary system does not.

Errata: I adjusted the years for double entry and Luca Pacioli.

Footnotes.

[1] reliably here means to play its part in the overall security model against attacks of fraud, etc.

[2] this rant is essentially a highly compressed version of:

http://iang.org/papers/triple_entry.html

[3] there is an intermediate step here where Bob can also sign the payment into a deposit instruction, thus confirming acceptance. But this can be optimised out. You can find out more about the signed transactional receipt model from Gary Howland's paper on SOX.

[4] think here of European Notaries, responsible to both parties to intermediate.

[5] crypto people would recall the term "non-repudiable" although that is out of favour; "non-repudiation is repudiated . BitCoin paper uses the term "non-reversible." Finance prefers terms like "final settlement. Legal people look for "evidence." I choose the legal term here because in a dispute their opinion matters more.

[6] this is not really apparent on paper, only in code and implementation (aka issues).

[7] all of this logic is applicable & analogous & consistent when the bookkeepers are computers...

[8] accounting history does not accept this point as proven. Having seen the difference of both double entry and triple entry in accounting systems, I'd say its clear. But historians don't have the benefit of seeing accounting systems stuff up in glorious fashion, they only have the dry old parchments to work from.

[9] another of the things essential on the list is final settlement / irreversibility / non-repudiation, as pioneered in many digital cash schemes. c.f., Mutual Funds Scandal.

[10] Everything important about the financial crisis in 4 short essays, start here: http://financialcryptography.com/mt/archives/001297.html

[11] http://financialcryptography.com/mt/archives/001126.html

This Season's BitCoin Collection:

- BitCoin and tulip bulbs

- Is BitCoin a triple entry system?

- BitCoin - the bad news

December 09, 2009

Bowles case is more evidence: Britain takes another step to a hollowed-out state

In the very sad story of the Justice System as we know it, a British courts has ruled the beginning of the end.

He went to jail this week, protesting his innocence. Speaking to The Times, he said: "There are no missing millions, there's no villa in the Virgin Islands, there has been no fraud. I am not allowed to earn any money, my assets were restrained so I couldn't use them to defend myself - it's a relentless, never-ending, vicious, cruel and wicked system.

Of course, all mobsters say that. So what was the crime?

Bowles was convicted by a jury in June of cheating the Revenue of £1.2 million in VAT but sentencing had been adjourned on three previous occasions. He had been found guilty of failing to pay VAT on a BIG land sale and diverting money due to the taxman to prop up Airfreight Express, his ailing air-freight company.

Now we have come full circle, and the evidence is presented: the Anti-money-laundering project of the OECD (known as the Financial Action Task Force, a Paris-based body) is basically and fundamentally inspired by the desire to raise tax. Hence, we will see a steady progression of government-revenue cases, occasionally interspersed with Mr Big cases. This is exactly what the OECD wanted. Not the mobsters, murderers, drug barons and terrorists pick up, but:

Bowles is a divorced, middle-aged company director from Maidenhead who has been transformed from successful entrepreneur to convicted fraudster.

A businessman, from the very heartland of English countryside. Not a dangerous criminal at all, but someone doing business. Not "them" but us. POCA or Proceeds of Crime Act is now an important revenue-raising tool:

It was not suggested that Bowles, who has no criminal record, had used the money to fund a luxury lifestyle. Nevertheless, when the Revenue began a criminal investigation into his affairs in 2006 all his assets were frozen under the powers of the Proceeds of Crime Act.Bowles was required to live on an allowance and rely on legal aid for his defence rather than pay out of his own resources. Defence lawyers claimed that preparation of Bowles's defence case was hampered further because his companies' financial records were in the hands of administrators.

The accounts were not disclosed until a court hearing in February this year, at which point Bowles sought permission to have a forensic accountant examine them to determine the VAT position. He was refused a relaxation of the restraint order to pay for a forensic accountants' report. The Legal Services Commission also declined to fund such a report from legal aid.

After the court was told that the records "could be considered by counsel with a calculator" the trial went ahead. Bowles was cleared of two charges but found guilty of a third.

It works this way. First the money is identified. Then, the crime is constructed, the assets are frozen, legal-aid is denied, and the businessman goes to jail. By the time he gets out of that, he probably cannot mount a defence anyway, and rights are just so much confetti. This stripping of rights is a well-known technique in law, as only 1 in 100 can then mount a recovery of rights action, it is often done when the job of the prosecutor is more important than rights.

Let's be realistic here and assume that Bowles was guilty of tax fraud. His local paper certainly thinks he was guilty:

A tax cheat from Maidenhead who dodged paying £1.3m in VAT has been jailed for three-and-a-half years. ... The court heard between October 2001 and July 2006 Bowles failed to submit VAT returns to HM Customs and Excise (HMCE) and then HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC). The VAT related to the sale of land for commercial development in Cardiff worth £7.5m.Following an HMRC criminal investigation Bowles, from Sandisplatt Road, was charged on three counts of 'cheating the revenue'. Peter Avery, assistant director, HMRC Criminal Investigations, said: "This sentence will serve as a deterrent to anyone who thinks that tax fraud is a risk worth taking."

Firstly, this is quite common, and secondly, tax is the most complicated thing in existence, so complicated that most ordinary lawyers don't recognise it as law by principle. It's the tax code, it's special. It's actually very hard not to be guilty of it, when you have a fair-sized business (whoever heard of a value-added-tax on a land sale?)

But even assuming that the guy was guilty, there was rather stunning evidence to the contrary, which underscores the point that this was revenue raising, not the bringing down of a Mr Big: