August 24, 2010

What would the auditor say to this?

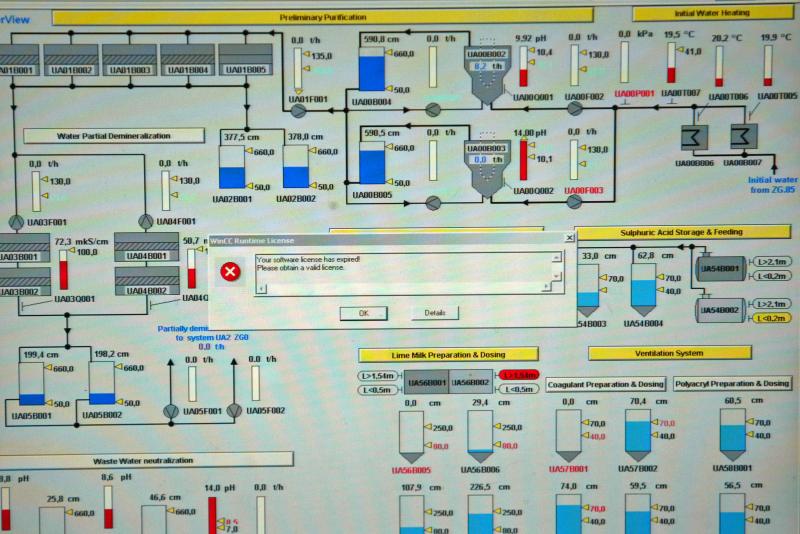

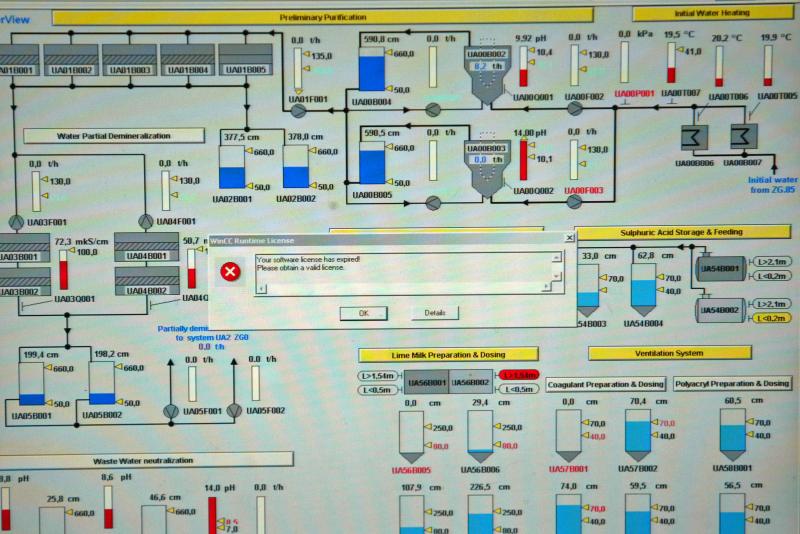

Iran's Bushehr nuclear power plant in Bushehr Port:

"An error is seen on a computer screen of Bushehr nuclear power plant's map in the Bushehr Port on the Persian Gulf, 1,000 kms south of Tehran, Iran on February 25, 2009. Iranian officials said the long-awaited power plant was expected to become operational last fall but its construction was plagued by several setbacks, including difficulties in procuring its remaining equipment and the necessary uranium fuel. (UPI Photo/Mohammad Kheirkhah)"

Click onwards for full sized image:

Compliant? Minor problem? Slight discordance? Conspiracy theory?

(spotted by Steve Bellovin)

August 21, 2010

memes in infosec IV - turn off HTTP, a small step towards "only one mode"

There appears to be a wave of something going through the infosec industry. There are reports like this:

In the past month, we've had several customers at work suddenly insist that we make modifications to their firewalls and/or load balancers to redirect *all* incoming HTTP traffic to HTTPS (which of course isn't always entirely sane to do on proxying devices, but they apparently don't trust their server admins to maintain an HTTP redirect). Most of them cited requirements from their PCI-DSS auditors. One apparently was outright told that their redirects were "a security problem" because they presented an open socket on port 80, and they needed to be refusing all HTTP to their servers at the firewall. I think we gave them sufficient wording to convince their auditor that blocking access to the redirect itself wasn't going to do anyone any good.

Then, there have been long discussions circulating around the meaning of this hypothesis in security design:

there is only one Mode, and it is Secure

Which, if I can say in small defence, is an end-point, a result, an arrival that does not in the slightest hint at how or why we got there. Or by what path, which by way of example is the topic of this very blog post.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has announced and pushed a new experimental browser plugin to take browsing on that very path towards more and pervasive HTTPS:

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has announced and pushed a new experimental browser plugin to take browsing on that very path towards more and pervasive HTTPS:

HTTPS Everywhere is a Firefox extension produced as a collaboration between The Tor Project and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. It encrypts your communications with a number of major websites.Many sites on the web offer some limited support for encryption over HTTPS, but make it difficult to use. For instance, they may default to unencrypted HTTP, or fill encrypted pages with links that go back to the unencrypted site.

The HTTPS Everywhere extension fixes these problems by rewriting all requests to these sites to HTTPS.

And Jeff Hodges, Collin Jackson and Adam Barth have published an Internet Draft called Strict Transport Security based on this paper, which in essence tells anyone who connects to the insecure HTTP service to instead switch across to the secure HTTPS service.

Now, leaving aside whether these innovations will cause a few confusions in compatibility, site-redesign and access, all common ills that we would normally bow and scrape before, ... it would seem that this time there is some emphasis behind it: As well as the EFF plugin above, Paypal and NoScript have adopted STS. As Paypal was at one time the number 1 target for phishing-style attacks, this carries some weight. And as NoScript is allegedly used by practically all the security people on the planet, this could be influential.

A few words on what appears to be happening here. In the Internet security field is that the 800lb gorilla -- breaches, viruses, botnets, phishing,... -- it seems that outsiders like EFF, Paypal and PCI-DSS auditors are starting cleaning up the field. And in this case, they're looking for easy targets.

One such target was long identified: turn off HTTP. Yup, throw another bundle of tinder on that fire that's burning around me ... but meanwhile, switch all HTTP traffic to HTTPS.

One such target was long identified: turn off HTTP. Yup, throw another bundle of tinder on that fire that's burning around me ... but meanwhile, switch all HTTP traffic to HTTPS.

In an ideal world, every web request could be defaulted to HTTPS.

It's a simple thing, and an approximate first step towards the hypothesis of there is only one mode and it is secure. Switching to HTTPS for everything does a few things, obvious and subtle.

1. the obvious thing is that the user can now be seriously expected to participate in the "watch the padlock" protocol, because she's no longer being trained to ignore the padlock by the rest of the site. The entire site is HTTPS, that's easy enough for the users to understand.

2. The second thing that the notion of pervasive HTTPS does is to strip away some (not all) of the excuses for other parties. Right now, most decision makers almost totally ignore HTTPS. Browser manufacturers, server manufacturers, CAs, cartels, included. It is all compliance thinking, all eyes are turned elsewhere. If, for any circumstance, for any user, for any decision maker, there is a failure, then there is also an easy excuse as to "why not." Why it didn't work, why I'm not to blame, why someone else should fix their problems.

Probably, there are more excuses than we can count (I once counted 99...) (the latest excuse from NIST, Mozilla and Microsoft).

However, if the PCI-DSS auditors make HTTPS the normal and only mode of operation, that act will strip away a major class of excuses. It's on, always on, only on. Waddya mean, it went off? This means the security model can actually be pinned on the suppliers and operators, more of the time. At least, the outrage can be pinned on them, when it doesn't work, and it will have some merit.

3. The third thing it does is move a lot of attention into the HTTPS sphere. This is much more important, but more subtle.

More attention, a growing market, more expectations means more certs, more traffic, more reliance on the server cert, etc. But it also means more attention to client certs, more programmers, more admins, more more more ...

Which will elevate the use of HTTPS and its entire security model overall; which will hopefully get the people who can make a difference -- here I'm thinking of Mozilla and Microsoft and the other browser security UI production teams -- to put a bit more effort and thinking into this problem.

Some would say they are working hard, and I know they are. But let me put this in context. Last I heard, Jonathan had a team of 2-3 programmers working on Firefox security UI. (And, yes, that's a set-up for a correction, thanks!)

This team is so tiny that we can even know their names.... Let me know and I'll post their names :)

Yet, this security UI is protecting the online access of probably 100 million people across the planet. And the current viewpoint of the owning organisation is that this is a backwater that isn't really important, other areas are much more important.

(Just to point out that I'm not picking on Mozilla unfairly: Microsoft is no better, albeit more clear in their economic reasoning. Google probably has one person, Opera may have one too. Konqueror? Apple won't say a thing...)

(Prove me wrong, guys! Ya know ya want to! :)

August 20, 2010

Niall Ferguson - Empires on the Edge of Chaos

Niall Ferguson spoke a few weeks ago at something called the CIS, supposedly a right-wing thinktank in Australia. He's well known for his Ascent of Money series, which is the thing you buy on DVD if you want to tell your Mum about economics and the way the world works. He's also that rarest breed in economics - he's not an economist at all, he's a historian.

Niall Ferguson spoke a few weeks ago at something called the CIS, supposedly a right-wing thinktank in Australia. He's well known for his Ascent of Money series, which is the thing you buy on DVD if you want to tell your Mum about economics and the way the world works. He's also that rarest breed in economics - he's not an economist at all, he's a historian.

His speech is here. It's a very big video download (26Mb), it seems, so I'll post this *after* my download else I'll never see it. Also, see it on vimeo directly which might work better.

Other writings on the same theme can be found in An Empire at Risk and America, the Fragile Empire. But frankly, the words in print don't do justice. It's a great presentation, both in terms of the picture it draws, the evidence assembled, and how well it was presented.

(The introduction of around 8-9 minutes is very skippable...) (Slightly edited to incorporate new links.)

August 13, 2010

Turning the Honeypot

I'm reading a govt. security manual this weekend, because ... well, doesn't everyone?

I'm reading a govt. security manual this weekend, because ... well, doesn't everyone?

To give it some grounding, I'm building up a cross-reference against my work at the CA. I expected it to remain rather dry until the very end, but I've just tripped up on this Risk in the section on detecting incidents:

2.5.7. An agency constructs a honeypot or honeynet to assist in capturing intrusion attempts, resulting in legal action being taken against the agency for breach of privacy.

My-oh-my!

August 12, 2010

memes in infosec II - War! Infosec is WAR!

Another metaphor (I) that has gained popularity is that Infosec security is much like war. There are some reasons for this: there is an aggressive attacker out there who is trying to defeat you. Which tends to muck a lot of statistical error-based thinking in IT, a lot of business process, and as well, most economic models (e.g., asymmetric information assumes a simple two-party model). Another reason is the current beltway push for essential cyberwarfare divisional budget, although I'd hasten to say that this is not a good reason, just a reason. Which is to say, it's all blather, FUD, and oneupsmanship against the Chinese, same as it ever was with Eisenhower's nemesis.

Another metaphor (I) that has gained popularity is that Infosec security is much like war. There are some reasons for this: there is an aggressive attacker out there who is trying to defeat you. Which tends to muck a lot of statistical error-based thinking in IT, a lot of business process, and as well, most economic models (e.g., asymmetric information assumes a simple two-party model). Another reason is the current beltway push for essential cyberwarfare divisional budget, although I'd hasten to say that this is not a good reason, just a reason. Which is to say, it's all blather, FUD, and oneupsmanship against the Chinese, same as it ever was with Eisenhower's nemesis.

Having said that, infosec isn't like war in many ways. And knowing when and why and how is not a trivial thing. So, drawing from military writings is not without dangers. Consider these laments about applying Sun Tzu's The Art of War to infosec from Steve Tornio and Brian Martin:

In "The Art of War," Sun Tzu's writing addressed a variety of military tactics, very few of which can truly be extrapolated into modern InfoSec practices. The parts that do apply aren't terribly groundbreaking and may actually conflict with other tenets when artificially applied to InfoSec. Rather than accept that Tzu's work is not relevant to modern day Infosec, people tend to force analogies and stretch comparisons to his work. These big leaps are professionals whoring themselves just to get in what seems like a cool reference and wise quote.

"The art of war teaches us to rely not on the likelihood of the enemy's not coming, but on our own readiness to receive him; not on the chance of his not attacking, but rather on the fact that we have made our position unassailable." - The Art of War

The Art of SunTzu is not a literal quoting and thence mad rush to build the tool. Art of War was written from the context of a successful general talking to another hopeful general on the general topic of building an army for a set piece nation-to-nation confrontation. It was also very short.

Art of War tends to interlace high level principles with low level examples, and dance very quickly through most of its lessons. Hence it was very easy to misinterpret, and equally easy to "whore oneself for a cool & wise quote."

However, Sun Tzu still stands tall in the face of such disrespect, as it says things like know yourself FIRST, and know the enemy SECOND, which the above essay actually agreed with. And, as if it needs to be said, knowing the enemy does not imply knowing their names, locations, genders, and proclivities:

Do you know your enemy? If you answer 'yes' to that question, you already lost the battle and the war. If you know some of your enemies, you are well on your way to understanding why Tzu's teachings haven't been relevant to InfoSec for over two decades. Do you want to know your enemy? Fine, here you go. your enemy may be any or all of the following:

- 12 y/o student in Ohio learning computers in middle school

- 13 y/o home-schooled girl getting bored with social networks

- 15 y/o kid in Brazil that joined a defacement group

- ...

Of course, Sun Tzu also didn't know the sordid details of every soldier's desires; "knowing" isn't biblical, it's capable. Or, knowing their capabilities, and that can be done, we call it risk management. As Jeffrey Carr said:

The reason why you don't know how to assign or even begin to think about attribution is because you are too consumed by the minutia of your profession. ... The only reason why some (OK, many) InfoSec engineers haven't put 2+2 together is that their entire industry has been built around providing automated solutions at the microcosmic level. When that's all you've got, you're right - you'll never be able to claim victory.

Right. Most all InfoSec engineers are hired to protect existing installations. The solution is almost always boxed into the defensive, siege mentality described above, because the alternate, as Dan Geer apparently said:

When you are losing a game that you cannot afford to lose, change the rules. The central rule today has been to have a shield for every arrow. But you can't carry enough shields and you can run faster with fewer anyhow.The advanced persistent threat, which is to say the offense that enjoys a permanent advantage and is already funding its R&D out of revenue, will win as long as you try to block what he does. You have to change the rules. You have to block his success from even being possible, not exchange volleys of ever better tools designed in response to his. You have to concentrate on outcomes, you have to pre-empt, you have to be your own intelligence agency, you have to instrument your enterprise, you have to instrument your data.

But, at a corporate level, that's simply not allowed. Great ideas, but only the achievable strategy is useful, the rest is fantasy. You can't walk into any company or government department and change the rules of infosec -- that means rebuilding the apps. You can't even get any institution to agree that their apps are insecure; or, you can get silent agreement by embarrassing them in the press, along with being fired!

I speak from pretty good experience of building secure apps, and of looking at other institutional or enterprise apps and packages. The difference is huge. It's the difference between defeating Japan and defeating Vietnam. One was a decision of maximisation, the other of minimisation. It's the difference between engineering and marketing; one is solid physics, the other is facade, faith, FUD, bribes.

It's the difference between setting up a world-beating sigint division, and fixing your own sigsec. The first is a science, and responds well by adding money and people. Think Manhattan, Bletchley Park. The second is a societal norm, and responds only to methods generally classed by the defenders as crimes against humanity and applications. Slavery, colonialism, discrimination, the great firewall of China, if you really believe in stopping these things, then you are heading for war with your own people.

Which might all lead the grumpy anti-Sun Tzu crowd to say, "told you so! This war is unwinnable." Well, not quite. The trick is to decide what winning is; to impose your will on the battleground. This is indeed what strategy is, to impose ones own definition of the battleground on the enemy, and be right about it, which is partly what Dan Geer is getting at when he says "change the rules." A more nuanced view would be: to set the rules that win for you; and to make them the rules you play by.

And, this is pretty easily answered: for a company, winning means profits. As long as your company can conduct its strategy in the face of affordable losses, then it's winning. Think credit cards, which sacrifice a few hundred basis points for the greater good. It really doesn't matter how much of a loss is made, as long as the customer pays for it and leaves a healthy profit over.

Relevance to Sun Tzu? The parable of the Emperor's Concubines!

Relevance to Sun Tzu? The parable of the Emperor's Concubines!

In summary, it is fair to say that Sun Tzu is one of those texts that are easy to bandy around, but rather hard to interpret. Same as infosec, really, so it is no surprise we see it in that world. Also, war as a very complicated business, and Art of War was really written for that messy discipline ... so it takes somewhat more than a familiarity from both to successfully relate across beyond a simple metaphor level.

And, as we know, metaphors and analogues are descriptive tools, not proofs. Proving them wrong proves nothing more than you're now at least an adolescent.

Finally, even war isn't much like war these days. If one factors in the last decade, there is a clear pattern of unilateral decisions, casus belli at a price, futile targets, and effervescent gains. Indeed, infosec looks more like the low intensity, mission-shy wars in the Eastern theaters than either of them look like Sun Tzu's campaigns.

memes in infosec I - Eve and Mallory are missing, presumed dead

August 05, 2010

Are we spending too little on security? Or are we spending too much??

Luther Martin asks this open question:

Ian,

I have a quick question for you based on some recent discussions. Here's the background.

The first was with a former co-worker who works for the VC division of a large commercial bank. He tells me that his bank really isn't interested in investing in security companies. Why? Apparently foreach $100 of credit card transactions there's about $4 of loss due to bad debt and about only $0.10 of loss due to fraud. So if you're making investments, it's clear where you should put your money.

Next, I was talking with a guy who runs a large credit card processing business. He was complaining about having to spend an extra $6 million on fraud reduction while his annual losses due to fraud are only about $250K.

Finally, I was also talking to some people from a government agency who were proud of the fact that they had reduced losses due to security incidents in their division by $2 million last year. The only problem is that they actually spent $10 million to do this.

So the question is this: are we not spending enough on security or are we spending too much, but on the wrong things?

Luther