January 29, 2012

Why Threat Modelling fails in practice

I've long realised that threat modelling isn't quite it.

There's some malignancy in the way the Internet IT Security community approached security in the 1990s that became a cancer in our protocols in the 2000s. Eventually I worked out that the problem with the aphorism What's Your Threat Model (WYTM?) was the absence of a necessary first step - the business model - which lack permitted threat modelling to be de-linked from humanity without anyone noticing.

But I still wasn't quite there, it still felt like wise old men telling me "learn these steps, swallow these pills, don't ask for wisdom."

In my recent risk management work, it has suddenly become clearer. Taking from notes and paraphrasing, let me talk about threats versus risks, before getting to modelling.

A threat is something that threatens, something that can cause harm, in the abstract sense. For example, a bomb could be a threat. So could an MITM, an eavesdropper, or a sniper.

But, separating the abstract from the particular, a bomb does not necessarily cause a problem unless there is a connection to us. Literally, it has to be capable of doing us harm, in a direct sense. For this reason, the methodologists say:

Risk = Threat * Harm

Any random bomb can't hurt me, approximately, but a bomb close to me can. With a direct possibility of harm to us, a threat becomes a risk. The methodologists also say:

Risk = Consequences * Likelihood

That connection or context of likely consequences to us suddenly makes it real, as well as hurtful.

A bomb then is a threat, but just any bomb doesn't present a risk to anyone, to a high degree of reliability. A bomb under my car is now a risk! To move from threats to risks, we need to include places, times, agents, intents, chances of success, possible failures ... *victims* ... all the rest needed to turn the abstract scariness into direct painful harm.

We need to make it personal.

To turn the threatening but abstract bomb from a threat to a risk, consider a plane, one which you might have a particular affinity to because you're on it or it is coming your way:

⇒ people dying⇒ financial damage to plane ⇒ reputational damage to airline⇒ collateral damage to other assets⇒ economic damage caused by restrictions⇒ war, military raids and other state-level responses

Lots of risks! Speaking of bombs as planes: I knew someone booked on a plane that ended up in a tower -- except she was late. She sat on the tarmac for hours in the following plane.... The lovely lady called Dolly who cleaned my house had a sister who should have been cleaning a Pentagon office block, but for some reason ... not that day. Another person I knew was destined to go for coffee at ground zero, but woke up late. Oh, and his cousin was a fireman who didn't come home that day.

Which is perhaps to say, that day, those risks got a lot more personal.

We all have our very close stories to tell, but the point here is that risks are personal, threats are just theories.

Let us now turn that around and consider *threat modelling*. By its nature, threat modelling only deals with threats and not risks and it cannot therefore reach out to its users on a direct, harmful level. Threat modelling is by definition limited to theoretical, abstract concerns. It stops before it gets practical, real, personal.

Maybe this all amounts to no more than a lot of fuss about semantics?

To see if it matters, let's look at some examples: If we look at that old saw, SSL, we see rhyme. The threat modelling done for SSL took the rather abstract notions of CIA -- confidentiality, integrity and authenticity -- and ended up inverse-pyramiding on a rather too-perfect threat of MITM -- Man-in-the-Middle.

We can also see from the lens of threat analysis versus risk analysis that the notion of creating a protocol to protect any connection, an explicit choice of the designers, led to them not being able to do any risk analysis at all; the notion of protecting certain assets such as credit cards as stated in the advertising blurb was therefore conveniently not part of the analysis (which we knew, because any risk analysis of credit cards reveals different results).

Threat modelling therefore reveals itself to be theoretically sound but not necessarily helpful. It is then no surprise that SSL performed perfectly against its chosen threats, but did little to offend the risks that users face. Indeed, arguably, as much as it might have stopped some risks, it helped other risks to proceed in natural evolution. Because SSL dealt perfectly with all its chosen threats, it ended up providing a false sense of false security against harm-incurring risks (remember SSL & Firewalls?).

OK, that's an old story, and maybe completely and boringly familiar to everyone else? What about the rest? What do we do to fix it?

The challenge might then be to take Internet protocol design from the very plastic, perfect but random tendency of threat modelling and move it forward to the more haptic, consequences-directed chaos of risk modelling.

Or, in other words, we've got to stop conflating threats with risks.

Critics can rush forth and grumble, and let me be the first: Moving to risk modelling is going to be hard, as any Internet protocol at least at the RFC level is generally designed to be deployed across an extremely broad base of applications and users.

Remember IPSec? Do you feel the beat? This might be the reason why we say that only end-to-end security cuts the mustard, because end-to-end implies an application, and this draw in the users to permit us to do real risk modelling.

It might then be impossible to do security at the level of an Internet-wide, application-free security protocol, a criticism that isn't new to the IETF. Recall the old ISO layer 5, sometimes called "the security layer" ?

But this doesn't stop the conclusion: threat modelling will always fail in practice, because by definition, threat modelling stops before practice. The place where users are being exposed and harmed can only be investigated by getting personal - including your users in your model. Threat modelling does not go that far, it does not consider the risks against any particular set of users that will be harmed by those risks in full flight. Threat modelling stops at the theoretical, and must by the law of ignorance fail in the practical.

Risks are where harm is done to users. Risk modelling therefore is the only standard of interest to users.

January 21, 2012

the emerging market for corporate issuance of money

As an aside to the old currency market currently collapsing, in the now universally known movie GFC-2 rolling on your screens right now, some people have commented that perhaps online currencies and LETS and so forth will fill the gap. Unlikely, they won't fill the gap, but they will surge in popularity. From a business perspective, it is then some fun to keep an eye on them. An article on Facebook credits by George Anders, which is probably the one to watch:

Facebook’s 27-year-old founder, Mark Zuckerberg, isn’t usually mentioned in the same breath as Ben Bernanke, the 58-year-old head of the Federal Reserve. But Facebook’s early adventures in the money-creating business are going well enough that the central-bank comparison gets tempting.

Let's be very clear here: the mainstream media and most commentators will have very little clue what this is about. So they will search for easy analogues such as a comparison with national units, leading to specious comparisons of Zuckerberg to Bernanke. Hopeless and complete utter nonsense, but it makes for easy copy and nobody will call them on it.

Edward Castronova, a telecommunications professor at Indiana University, is fascinated by the rise of what he calls “wildcat currencies,” such as Facebook Credits. He has been studying the economics of online games and virtual worlds for the better part of a decade. Right now, he calculates, the Facebook Credits ecosystem can’t be any bigger than Barbados’s economy and might be significantly smaller. If the definition of digital goods keeps widening, though, he says, “this could be the start of something big.”

This is a little less naive and also slightly subtle. Let me re-write it:

If you believe that Facebook will continue to dominate and hold its market size, and if you believe that they will be able to successfully walk the minefield of self-issued currencies, then the result will be important. In approximate terms, think about PayPal-scaled importance, order of magnitude.

Note the assumptions there. Facebook have a shot at the title, because they have massive size and uncontested control of their userbase. (Google, Apple, Microsoft could all do the same thing, and in a sense, they already are...)

The more important assumption is how well they avoid the minefield of self-issued currencies. The problem here is that there are no books on it, no written lore, no academic seat of learning, nothing but the school of hard-knocks. To their credit, Facebook have already learnt quite a bit from the errors of their immediate predecessors. Which is no mean feat, as historically, self-issuers learn very little from their forebears, which is a good predictor of things to come.

Of the currency issuers that spring up, 99% are destined to walk on a mine. Worse, they can see the mine in front of them, they successfully aim for it, and walk right onto it with aplomb. No help needed at all. And, with 15 years of observation, I can say that this is quite consistent.

Why? I think it is because there is a core dichotomy at work here. In order to be a self-issuer you have to be independent enough to not need advice from anyone, which will be familiar to business observers as the entrepreneur-type. Others will call it arrogant, pig-headed, too darned confident for his own good... but I prefer to call it entrepreneurial spirit.

*But* the issuance of money is something that is typically beyond most people's ken at an academic or knowledge level. Usage of money is something that we all know, and all learnt at age 5 or so. We can all put a predictions in at this level, and some players can make good judgements (such as Peter Vodel's Predictions for Facebook Credits in 2012).

Issuance of money however is a completely different thing to usage. It is seriously difficult to research and learn; by way of benchmark, I wrote in 2000 you need to be quite adept at 7 different disciplines to do online money (what we then called Financial Cryptography). That number was reached after as many years of research on issuance, and nearly that number working in the field full time.

And, I still got criticised by disciplines that I didn't include.

Perhaps fairly...

You can see where I'm heading. The central dichotomy of money issuance then is that the self-issuer must be both capable of ignoring advice, and putting together an overwhelming body of knowledge at the same time; which is a disastrous clash as entrepreneurs are hopeless at blindspots, unknowns, and prior art.

There is no easy answer to this clash of intellectual challenges. Most people will for example assume that institutions are the way to handle any problem, but that answer is just another minefield:

If Facebook at some point is willing to reduce its cut of each Credits transaction, this new form of online liquidity may catch the eye of many more merchants and customers. As Castronova observes: “there’s a dynamic here that the Federal Reserve ought to look at.”

Now, we know that Castronovo said that for media interest only, but it is important to understand what really happens with the Central Banks. Part of the answer here is that they already do observe the emerging money market :) They just won't talk to the media or anyone else about it.

Another part of the answer is that CBs do not know how to issue money either; another dichotomy easily explained by the fact that most CBs manage a money that was created a long time ago, and the story has changed in the telling.

So, we come to the the really difficult question: what to do about it? CBs don't know, so they will definately keep the stony face up because their natural reaction to any question is silence.

But wait! you should be saying. What about the Euro?

Well, it is true that the Europeans did indeed successfully manage to re-invent the art and issue a new currency. But, did they really know what they were doing? I would put it to you that the Euro is the exception that proves the rule. They may have issued a currency very well, but they failed spectacularly in integrating that currency into the economy.

Which brings us full circle back to the movie now showing on media tonight and every night: GFC-2.

for bright times for CISOs ... turn on the light!

Along the lines of "The CSO should have an MBA" we have some progress:

City University London will offer a new postgraduate course from September, designed to help information security and risk professionals progress to managerial roles.The new Masters in Information Security and Risk (MISR) aims to address a gap in the market for IT professionals that can “speak business”. One half of the course is devoted to security strategy, risk management and security architecture, while the other half focuses on putting this into a business-oriented context.

“Talking to people out in the industry, particularly if you go to the financial sector, they say one real problem is they don't have a security person who they can take along to the board meeting without having to act as an interpreter; so we're putting together a programme to address this need,” explained course director Professor Kevin Jones, speaking at the Infosecurity Europe Press Conference in London yesterday.

January 08, 2012

Why we got GFC-2

And so it came to pass that, after my aggressive little note on GFC-1's causes found in securitization (I, II, III, IV), I am asked to describe the current, all new with extra whitening Global Financial Crisis - the Remix, or GFC-2 to those who love acronyms and the pleasing rhyme of sequels.

Or, the 2nd Great Depression, depending on how it pans out. Others have done it better than I, but here is my summary.

Part 1. In 2000, European countries joined together in the EMU or European Monetary Union. A side-benefit of this was the Bundesbank's legendary and robust control of inflation and stiff conservative attitude to matters monetary. Which meant other countries more or less got to borrow at Bundesbank's rates, plus a few BPs (that's basis points, or hundredths of percentage points for you and I).

Imagine that?! Italy, who had been perpetually broke under the old Lira, could now borrow at not 6 or 7% but something like 3%. Of course, she packed her credit card and went to town, as 3% on the CC meant she could buy twice as much stuff, for the same regular monthly payments. So did Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Spain. Everyone in the EMU, really.

The problem was, they still had to pay it back. Half the interest with the same serviceable monthly credit card bill means you can borrow twice as much. Leverage! It also means that if the rates move against you, you're in it twice as deep.

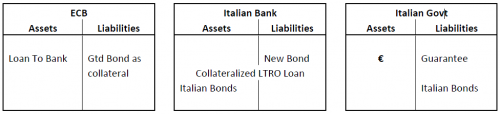

And the rates, they did surely move. For this we can blame GFC-1 which put the heebie-jeebies into the market and caused them to re-evaluate the situation. And, lo and behold, the European Monetary Union was revealed as no more than a party trick because Greece was still Greece, banks were still banks, debt was still debt, and the implicit backing from the Bundesbank was ... not actually there! Or the ECB, which by charter isn't allowed to lend to governments nor back up their foolish use of the credit card.

Bang! Rates moves up to the old 6 or 7%, and Greece was bankrupt.

Now we get to Part 2. It would have been fine if it had stopped there, because Greece could just default. But the debt was held by (owed to) ... the banks. Greece bankrupt ==> banks bankrupt. Not just or not even the Greek ones but all of them: as financing governments is world-wide business, and the balance sheets of the banks post-GFC-1 and in a non-rising market are anything but 'balanced.' Consider this as Part 0.

Now stir in a few more languages, a little contagion, and we're talking *everyone*. To a good degree of approximation, if Greece defaults, USA's banking system goes nose deep in it too.

So we move from the countries, now the least of our problems because they can simply default ... to the banks. Or, more holistically, the entire banking system. Is bankrupt.

In its current today form, there is the knowledge that the banks cannot deal with the least hiccup. Every bank knows this, knows that if another bank defaults on a big loan, they're in trouble. So every bank pulls its punches, liquidity dries up, and credit stops flowing ... to businesses, and the economy hits a brick wall. Internationally.

In other words, the problem isn't that countries are bankrupt, it is that they are not allowed to go bankrupt (clues 1, 2).

We saw something similar in the Asian Financial Crisis, where countries were forced to accept IMF loans ... which paid out the banks. Once the banks had got their loans paid off, they walked, and the countries failed (because of course they couldn't pay back the loans). Problem solved.

This time however there is no IMF, no external saviour for the banking system, because we are it, and we are already bankrupt.

Well, there. This is as short as I can get the essentials. We need scholars like Kevin Dowd or John Maynard Keynes, those whos writing is so clear and precise as to be intellectual wonders in their own lifetimes. And, they will emerge in time to better lay down the story - the next 20 years are going to be a new halcyon age of economics. So much to study, so much new raw data. Pity they'll all be starving.