February 29, 2012

Google thought about issuing a currency

Chris points to:

Google once considered issuing its own currency, to be called Google Bucks, company Chairman Eric Schmidt said on stage in Barcelona at the Mobile World Congress Tuesday.At the end of his keynote speech, Schmidt hit on a wide array of topics in response to audience questions. "We've had various proposals to have our own currency we were going to call Google Bucks," Schmidt said.

The idea was to implement a "peer-to-peer money" system. However, Google discovered that the concept is illegal in most areas, he said. Governments are typically wary of the potential for money laundering with such proposals. "Ultimately we decided we didn't want to get into that because of these issues," Schmidt said.

Offered without too much analysis. This confirms what we suspected - that they looked at it and decided not to. Technically, this is a plausible and expected decision that will be echoed by many conventional companies. I would expect Apple to do this too, and Microsoft know this line very well.

However we need to understand that this result is intentional, the powers that be want you to think this way. Banks want you to play according to their worldview, and they want you to be scared off their patch. Sometimes however they don't tell the whole truth, and as it happens, p2p is not illegal in USA or Europe - the largest markets. You are also going to find surprising friends in just about any third world country.

Still, google did their own homework, and at least they investigated. As a complicated company with many plays, they and they alone must do their strategy. Still, as we move into GFC-2 with the probability of mass bank nationalisations in order to save the payments systems, one wonders how history will perceive their choice.

February 28, 2012

Serious about user security? Plonk down a million in prizes....

Google offers $1 million reward to hackers who exploit Chrome

By Dan Goodin | Published February 27, 2012 8:30 PM

Google has pledged cash prizes totaling $1 million to people who successfully hack its Chrome browser at next week's CanSecWest security conference.

Google will reward winning contestants with prizes of $60,000, $40,000, and $20,000 depending on the severity of the exploits they demonstrate on Windows 7 machines running the browser. Members of the company's security team announced the Pwnium contest on their blog on Monday. There is no splitting of winnings, and prizes will be awarded on a first-come-first-served basis until the $1 million threshold is reached.

Now in its sixth year, the Pwn2Own contest at the same CanSecWest conference awards valuable prizes to those who remotely commandeer computers by exploiting vulnerabilities in fully patched browsers and other Internet software. At last year's competition, Internet Explorer and Safari were both toppled but no one even attempted an exploit against Chrome (despite Google offering an additional $20,000 beyond the $15,000 provided by contest organizer Tipping Point).

Chrome is currently the only browser eligible for Pwn2Own never to be brought down. One reason repeatedly cited by contestants for its lack of attention is the difficulty of bypassing Google's security sandbox.

"While we’re proud of Chrome’s leading track record in past competitions, the fact is that not receiving exploits means that it’s harder to learn and improve," wrote Chris Evans and Justin Schuh, members of the Google Chrome security team. "To maximize our chances of receiving exploits this year, we’ve upped the ante. We will directly sponsor up to $1 million worth of rewards."

In the same blog post, the researchers said Google was withdrawing as a sponsor of the Pwn2Own contest after discovering rule changes allowing hackers to collect prizes without always revealing the full details of the vulnerabilities to browser makers.

"Specifically, they do not have to reveal the sandbox escape component of their exploit," a Google spokeswoman wrote in an email to Ars. "Sandbox escapes are very dangerous bugs so it is not in the best interests of user safety to have these kept secret. The whitehat community needs to fix them and study them. Our ultimate goal here is to make the web safer."

In a tweet, Aaron Portnoy, one of the Pwn2Own organizers, took issue with Google's characterization that the rules had changed and said that the contest has never required the disclosure of sandbox escapes.

Ars will have full coverage of Pwn2Own, which commences on Wednesday, March 7.

February 25, 2012

Signatures on fax & email - if you did not intend to be bound, why did you bother to write it?

(Cambridge University Press writes:)

Electronic Signatures in Law is now its third edition (published in January 2012 by Cambridge University Press). This edition provides an exhaustive discussion of what constitutes an electronic signature, the forms an electronic signature can take and the issues relating to evidence, formation of contract and negligence in respect of electronic signatures.Case law from a wide range of common law and civil law jurisdictions is analysed to illustrate how judges have dealt with changes in technology in the past and how the law has adapted in response.

For those who are unfamiliar, Stephen Mason's tome is *the comprehensive text* dealing with how cryptographic digsigs and other forms of technology interact with the law of agreement and contract. It's big, expensive, authoritative, and essential -- I've reached for my 2nd Edition dozens of times to resolve real dilemmas in business and tech.

And on this occasion, Stephen Mason has written a short essay on why real-life signing and agreement can be simplified from the idealistic view of the cryptographers:

Signatures on facsimile transmissions and e-mailBy Stephen Mason

The manuscript signature has a number of purposes, one of which is to provide evidence that the signatory approves and adopts the contents of the document, and that the content of the document is binding (for a more detailed discussion of the various purposes of the signature see chapter 1 of Stephen Mason, Electronic Signatures in Law (3rd edn, Cambridge University Press, 2012)). It is also possible to use a signature as a means of authentication, although what has become important in the virtual world is the process of verification, which Bruce Schneier illustrates in his article in Wired, ‘Why Do We Accept Signatures by Fax?’[1] dated 29 May 2008.

A signature sent by facsimile transmission is a mechanical mark, and the cases relating to facsimile transmissions (with one exception, for which see below) reach the same conclusions as for the telegram cases: that a name typed or written and then communicated over a telegram wire or telephone line is capable of proving intent. Evidence of intent is the point. Security is not the issue. Security has never been the issue in common law countries. Judges make decisions based on the way people in business conduct their affairs. If the record is signed with the requisite intent, that is sufficient.

Concern for the security of the signature largely came about because we started trusting the communications between bits of software. However, from the practical point of view, people in business have again left the issue of security behind. Millions of contracts are entered over the internet every day using a popular form of electronic signature – the ‘I accept’ icon. In such cases, the seller is only interested in whether the buyer is good for the money.

There is one case that does not follow the decisions of the other judges. In the New York case of Parma Tile Mosaic & Marble Co., Inc. v. Estate of Fred Short, d/b/a Sime Construction Co [2], it was decided that the automatic imprinting by the facsimile machine of the name of the sender at the top of each page transmitted did not satisfy the requirement under the Statute of Frauds that writing shall be subscribed.

I suggest that this decision was not correct (for my reasoning, see pp 80 – 81). On reflection, I have further concluded that the decision is also not correct because of the case law relating to the use of a printed name (see pp 39 – 48), where the name printed on a letterhead has been held to be a signature by judges in England and the United States of America.

The reasoning is as follows: a human being instructs a printer to print letterheads as official stationery. When the person or legal entity sends out an item of stationery with their details printed on the paper, they are stating who they are, and that they are responsible for the contents recorded on the paper. It is the same for facsimile transmissions. A human being programmes the machine to print the same information contained on the letterhead of a piece of stationery, and the information is printed on the paper that emerges from the recipient’s machine. Conceptually, there is no difference between the stationery and the facsimile transmission. Naturally, both can be misused or forged, but these are separate issues.

The same can be said of a form of electronic signature that is widely used: typing the name in an e-mail. Judges from across the world have accepted this form of electronic signature (see pp 193 – 215 for case law). In business, the general practice is to write a ‘signature’ or a number of different ‘signatures’ into the e-mail software, each to be used for a particular purpose. The user then instructs the software to include the signature block each time they send an e-mail.

That this signature block is included automatically is not relevant to the issue as to whether the person intended to sign the e-mail or not. What is relevant is whether, when writing and sending the e-mail, they intended to be bound by the contents. If they did not intend to be bound by the content of the e-mail, why did they bother writing it?

References

[1] http://www.schneier.com/essay-220.html. See also a discussion at Financial Cryptography: http://financialcryptography.com/mt/archives/001056.html.

[2] 155 Misc.2d 950, 590 N.Y.S.2d 1019 (Supp. 1992), motion for summary judgment affirmed, 209 A.D.2d 495, 619 N.Y.S.2d 628 reversed 663 N.E.2d 633 (N.Y. 1996), 640 N.Y.S.2d 477 (Ct.App. 1996), 87 N.Y.2D 524).

© Stephen Mason, 2012

http://stephenmason.co.uk

Electronic Signatures in Law, 3rd Edition

Author: Stephen Mason, Chambers of Stephen Mason

Format: Hardback

Series: Law Practitioner Series

ISBN: 9781107012295

Publication date:January 2012

Extent: 408 pages

February 18, 2012

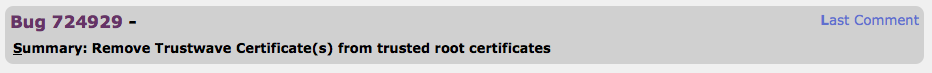

one week later - chewing on the last morsel of Trust in the PKI business

After a week of fairly strong deliberations, Mozilla has sent out a message to all CAs to clarify that MITM activity is not acceptable.

It would seem that Trustwave might slip through without losing their spot in the root list of major vendors. The reasons for this is a combination of: up-front disclosure, a short timeframe within which the subCA was issued and used (at this stage limited to 2011), and the principle of wiser heads prevailing.

It would seem that Trustwave might slip through without losing their spot in the root list of major vendors. The reasons for this is a combination of: up-front disclosure, a short timeframe within which the subCA was issued and used (at this stage limited to 2011), and the principle of wiser heads prevailing.

That's my assessment at least.

My hope is that this has set the scene. The next discovery will be fatal for that CA. The only way forward for a CA that has issued at any time in the past an MITM-enabled subCA would be the following:

+ up-front disclosure to the public. By that I mean, not privately to Mozilla or other vendors. That won't be good enough. Nobody trusts the secret channels anymore.

+ in the event that this is still going on, an *fast* plan, agreed and committed to vendors, to withdraw completely any of these MITM sub-CAs or similar arrangements. By that I mean *with prejudice* to any customers - breaching contract if necessary.

Any deviation means termination of the root. Guys, you got one free pass at this, and Trustwave used it up. The jaws of Trust are hungry for your response.

That is what I'll be looking for at Mozilla. Unfortunately there is no forum for Google and others, so Mozilla still remains the bellwether for trust in CAs in general.

That's not a compliment; it's more a description of how little trust there is. If there is a desire to create some, that's possibly where we'll see the signs.

The Convergence of PKI

Last week's post on the jaws of Trust sparked a bit of interest, and Chris asks what I think about Convergence in comments. I listened to this talk by Moxie Marlinspike, and it is entertaining.

The 'new idea' is not difficult. The idea of Convergence is for independent operators (like CAcert or FSFE or FSF) to run servers that cache certificates from sites. Then, when a user browser comes across a new certificate, instead of accepting the fiat declaration from the CA, it gets a "second opinion" from one of these caching sites.

Convergence is best seen as conceptually extending or varying the SSH or TOFU model that has already been tried in browsers through CertPatrol, Trustbar, Petnames and the like.

In the Trust-on-first-use model, we can make a pretty good judgement call that the first time a user comes to a site, she is at low risk. It is only later on when her relationship establishes (think online banking) that her risk rises.

This risk works because likelihood of an event is inversely aligned with the cost of doing that attack. One single MITM might be cost X, two might be X+delta, so as it goes on it gets more costly. In two ways: firstly, in maintaining the MITM over time against Alice costs go up more dramatically than linear additions of a small delta. In this sense, MITMs are like DOSs, they are easier to mount for brief periods. Secondly, because we don't know of Alice's relationship before hand, we have to cast a very broad net, so a lot of MITMs are needed to find the minnow that becomes the whale.

First-use-caching or TOFU works then because it forces the attacker into an uneconomic position - the easy attacks are worthless.

Convergence then extends that model by using someone else's cache, thus further boxing the attacker in. With a fully developed Convergence network in place, we can see that the attacker has to conduct what amounts to being a perfect MITM closer to the site than any caching server (at least at the threat modelling level).

Which in effect means he owns the site at least at the router level, and if that is true, then he's probably already inside and prefers more sophisticated breaches than mucking around with MITMs.

Thus, the very model of a successful mitigation -- this is a great risk for users to accept if only they were given the chance! It's pretty much ideal on paper.

Now move from paper threat modelling to *the business*. We can ask several questions. Is this better than the fiat or authority model of CAs which is in place now? Well, maybe. Assuming a fully developed network, Convergance is probably in the ballpark. A serious attacker can mount several false nodes, something that was seen in peer2peer networks. But a serious attacker can take over a CA, something we saw in 2011.

Another question is, is it cheaper? Yes, definately. It means that the entire middle ground of "white label" HTTPS certs as Mozilla now shows them can use Convergence and get approximately the same protection. No need to muck around with CAs. High end merchants will still go for EV because of the branding effect sold to them by vendors.

A final question is whether it will work in the economics sense - is this going to take off? Well, I wish Moxie luck, and I wish it work, but I have my reservations.

Like so many other developments - and I wish I could take the time to lay out all the tall pioneers who provided the high view for each succeeding innovation - where they fall short is they do not mesh well with the current economic structure of the market.

In particular, one facet of the new market strikes me as overtaking events: the über-CA. In this concept, we re-model the world such that the vendors are the CAs, and the current crop are pushed down (or up) to become sub-CAs. E.g., imagine that Mozilla now creates a root cert and signs individually each root in their root list, and thus turns it into a sub-root list. That's easy enough, although highly offensive to some.

Without thinking of the other ramifications too much, now add Convergance to the über-CA model. If the über-CA has taken on the responsibility, and manages the process end to end, it can also do the Convergence thing in-house. That is, it can maintain its set of servers, do the crawling, do the responding. Indeed, we already know how to do the crawling part, most vendors have had a go at it, just for in-house research.

Why do I think this is relevant? One word - google. If the Convergence idea is good (and I do think it is) then google will have already looked at it, and will have already decided how to do it more efficiently. Google have already taken more steps towards ueber-CA with their decision to rewire the certificate flow. Time for a bad haiku.

Google sites are pinned now / All your 'vokes are b'long to us / Cache your certs too, soon.

And who is the world's expert at rhyming data?

Which all goes to say that Convergence may be a good idea, a great one even, but it is being overtaken by other developments. To put it pithily the market is converging on another direction. 1-2 years ago maybe, yes, as google was still working on the browser at the standards level. Now google are changing the way things are done, and this idea will fall out easily in their development.

(For what it is worth, google are just as likely to make their servers available for other browsers to use anyway, so they could just "run" the Convergance network. Who knows. The google talks to no-one, until it is done, and often not even then.)

February 09, 2012

PKI and SSL - the jaws of trust snap shut

As we all know, it's a right of passage in the security industry to study the SSL business of certificates, and discover that all's not well in the state of Denmark. But the business of CAs and PKI rolled on regardless, seemingly because no threat ever challenged it. Because there was no risk, the system successfully dealt with the threats it had set itself. Which is itself elegant proof that academic critiques and demonstrations and phishing and so forth are not real attacks and can be ignored entirely...

Until 2011.

Last year, we crossed the Rubicon for the SSL business -- and by extension certificates, secure browsing, CAs and the like -- with a series of real attacks against CAs. Examples include the DigiNotar affair, the Iranian affair (attacks on around 5 CAs), and also the lesser known attack a few months back where certificates may have been forged and may have been used in an APT and may have... a lot of things. Nobody's saying.

Either way, the scene is set. The pattern has emerged, the Rubicon is crossed, it gets worse from here on in. A clear and present danger, perhaps? In California, they'd be singing "let's partly like it's 2003," the year that SB1386 slid past our resistance and set the scene for an industry an industry debacle in 2005.

But for us long term observers, no party. There will now be a steady series of these shocks, and journalists will write of our brave new world - security but no security.

With one big difference. Unlike the SB1386 breach party, where we can rely on companies not going away (even as our data does), the security system of SSL and certificates is somewhat optional. Companies can and do expose their data in different ways. We can and do invent new systems to secure or mitigate the damage. So while SB1386 didn't threaten the industry so much as briskly kicked it around, this is different.

At an attacks level, we've crossed a line, but at a wider systems level, we stand on the line.

Which brings us to this week's news. A CA called Trustwave has just admitted to selling a sub-root for the explicit purpose of MITM'ing. Read about that elsewhere.

Now, we've known that MITMing for fun and profit was going on for a long time. Mozilla's community first learnt of it in the mid 2000s as it was finalising its policy on CAs (a ground-breaking work that I was happy to be involved with). At that time, accusations were circulating against unknown companies listing their roots for the explicit purpose of doing MITMs on unwitting victims. Which raised the hairs, eyebrows and heckles on not a few of us. These accusations have been repeated from time to time, but in each case the "insiders" begged off on the excuse: we cannot break NDA or reputation.

Each time then the industry players were likewise able to fob it off. Hard Evidence? none. Therefore, it doesn't exist, was they industry's response. We knew as individuals, yet as an industry we knew not.

We are all agreed it does exist and it doesn't. We all have jobs to preserve, and will practice cognitive dissonance to the very end.

Of course this situation couldn't last, because a secret of this magnitude never survives. In this case, the company that sold the MITM sub-root, Trustwave, has looked at 2011, and realised the profit from that one CA isn't worth the risk of the DigiNotar experience (bankruptcy). Their decision is to 'fess up now, take it on the chin, because later may be too late.

Which leads to a dilemma, and we the players have divided on each side, one after the other, of that dilemma:

To drop the Trustwave root, or not?

To drop the Trustwave root, or not?

That is the question. First the case for the defence: On the one hand, we applaud the honesty of a CA coming forward and cleaning up house. It's pretty clear that we need our CAs to do this. Otherwise we're not going to get anywhere with this Trust thing. We need to encourage the CAs to work within the system.

Further, if we damage a CA, we damage customers. The cost to lost business is traumatic, and the list of US government agencies that depend on this CA has suddenly become impressive. Just like DigiNotar, it seems, which spread like a wave of mistrust through the government IT departments of the Netherlands. Also, we have to keep an eye on (say) a bigger more public facing CA going down in the aftermath - and the damage to all its customers. And the next, etc.

Is lost business more important than simple faith in those silly certificates? I think lost business is much more important - revenue, jobs, money flowing keeping all of the different parts of the economy going are our most important asset. Ask any politician in USA or Europe or China; this is their number one problem!

Finally, it is pretty clear and accepted that the business purpose to which the sub-Root was put was known and tolerated. Although it is uncomfortable to spy on ones employees, it is just business. Organisations own their data systems, have the responsibility to police them, and have advised their people that this is what they are going to do. SSL included, if necessary.

This view has it that Trustwave has done the right thing. Therefore, pass. And, the more positive proponents suggest an amnesty, after which period there is summary execution for the sins - root removal from the list distributed by the browsers. It's important to not cause disruption.

Now the case for the Prosecution! On the other hand, damn spot: the CA clearly broke their promise. Out!

Three ways, did they breach the trust: It is expressed in the Mozilla policy and presumably of others that certificates are only issued to people who own/control their domains. This is no light or optional thing -- we rely on the policy because CAs and Mozilla and other vendors and auditors and all routinely practice secrecy in this business.

We *must rely on the policy* because they deny us the right to rely on anything else!

Secondly, it is what the public believe in, it is the expectations of any purchaser or user of the product, written or not. It is a simple message, and brooks no complicated exceptions. Either your connection is secure to your online bank, and nobody else can see it *including your employer or IT department*. Or not.

Try explaining this exception to your grandmother, if the words do not work for you.

Finally, the raison d'être: it is the purpose and even the entire goal of the certificate design to do exactly the opposite. The reason we have CAs like TrustWave is to stop the MITM. If they don't stop the MITM, then *we don't need the heavyweight certificate system*, we don't need CAs, and we don't need Mozilla's root list or that of any other vendor.

We can do security much more cost-effectively if we drop the 100% always-on absolutist MITM protection.

Given this breach of trust, what else can we trust in? Can we trust their promises that the purpose was maintained? That the cert never left the building? That secret traffic wasn't vectored in? That HSMs are worth something and audits ensure all is well in Denmark?

This rather being a problem with trust. Lie once, lose it.

There being two views presented, it has to be said that both views are valid. The players are lining up on either side of the line, but they probably aren't so well aware of where this is going.

Only one view is going to win out. Only one side wins this fight.

And in so-doing, in winning, the winner sews the seeds for own destruction.

Because if you religiously take your worldview, and look at the counter-argument to your preferred position, your thesis crumbles for the fallacies.

The jaws of trust just snapped shut on the players who played too long, too hard, too profitably.

Like the financial system. We are no longer worried about the bankruptcy of one or two banks or a few defaults by some fly specks on the map of European. We are now looking at a change that will ripple out and remove what vestiges of purpose and faith were left in PKI. We are now looking at all the other areas of the business that will be effected; ones that brought into the promise even though they knew they shouldn't have.

Like the financial system, a place of uncanny similarity, each new shock makes us wonder and question. Wasn't all this supposed to be solved? Where are the experts? Where is the trust?

We're about to find out the timeless meaning of Caveat Emptor.