September 18, 2009

Where does the accounting profession want to go, today?

So, if they are not doing audits and accounting, where does the accounting profession want to go? Perhaps unwittingly, TOdd provided the answer with that reference to the book Accounting Education: Charting the Course through a Perilous Future by W. Steve Albrecht and Robert J. Sack.

So, if they are not doing audits and accounting, where does the accounting profession want to go? Perhaps unwittingly, TOdd provided the answer with that reference to the book Accounting Education: Charting the Course through a Perilous Future by W. Steve Albrecht and Robert J. Sack.

It seems that Messrs Albrecht and Sack, the authors of that book, took the question of the future of Accounting seriously:

Sales experts long ago concluded that "word of mouth" and "personal testimonials" are the best types of advertising. The Taylor Group1 found this to be true when they asked high school and college students what they intended to study in college. Their study found that students were more likely to major in accounting if they knew someone, such as a friend or relative, who was an accountant.

So they tested it by asking a slightly more revealing question of the accounting professionals:

When asked "If you could prepare for your professional career by starting college over again today, which of the following would you be most likely to do?" the responses were as follows:

Type of Degree % of Educators Who Would % of Practitioners Who Would Who Would Earn a bachelor's degree in something other than accounting and then stop 0.0 7.8 Earn a bachelor's degree in accounting, then stop 4.3 6.4 Earn a Master's of Business Administration (M.B.A.) degree 37.7 36.4 Earn a Master's of Accountancy degree 31.5 5.9 Earn a Master's of Information Systems degree 17.9 21.3 Earn a master's degree in something else 5.4 6.4 Earn a Ph.D. 1.6 4.4 Earn a J.D. (law degree) 1.6 11.4 These results are frightening,...

Well indeed! As they say:

It is telling that six times as many practicing accountants would get an M.B.A. as would an M.Acc., over three times as many practitioners would get a Master's of Information Systems degree as would get an M.Acc., and nearly twice as many practitioners would get a law degree instead of an M.Acc. Together, only 12.3 percent (6.4% + 5.9%) of practitioners would get either an undergraduate or graduate degree in accounting.2 This decrease in the perceived value of accounting degrees by practitioners is captured in the following quotes:We asked a financial executive what advice he would give to a student who wanted to emulate his career. We asked him if he would recommend a M.Acc. degree. He said, "No, I think it had better be broad. Students should be studying other courses and not just taking as many accounting courses as possible. ...My job right now is no longer putting numbers together. I do more analysis. My finance skills and my M.B.A. come into play a lot more than my CPA skills.

.... we are creating a new course of study that will combine accounting and

information technology into one unique major.......I want to learn about information systems.

(Of course I'm snipping out the relevant parts for speed, you should read the whole lot.) Now, we could of course be skeptical because we know computing is the big thing, it's the first addition to the old list of Reading, Arithmetic and Writing since the dark ages. Saying that Computing is core is cliche these days. But the above message goes further, it's almost saying that Accountants are better off not doing accounting!

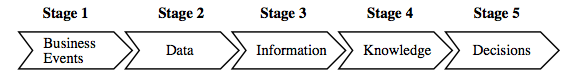

The Accounting profession of course can be relied upon to market their profession. Or can they? Todd was on point when he mentioned the value chain, the image in yesterday's post. Let's look at the wider context of the pretty picture:

Robert Elliott, KPMG partner and current chairman of the AICPA, speaks often about the value that accountants can and should provide. He identifies five stages of the "value chain" of information. The first stage is recording business events. The second stage is summarizing recorded events into usable data. The third stage is manipulating the data to provide useful information. The fourth stage is converting the information to knowledge that is helpful to decision makers. The fifth and final stage is using the knowledge to make value-added decisions. He uses the following diagram to illustrate this value chain:This five-stage breakdown is a helpful analysis of the information process. However, the frightening part of Mr. Elliott's analysis is his judgment as to what the segments of the value chain are worth in today's world. Because of the impact of technology, he believes that:

- Stage 1 activity is now worth no more than $10 per hour

- Stage 2 activity is now worth no more than $30 per hour

- Stage 3 activity is now worth $100 per hour

- Stage 4 activity is now worth $300 per hour

- Stage 5 activity is now worth $1,000 per hour

In discussing this value chain, Mr. Elliott urges the practice community to focus on upper-end services, and he urges us to prepare our students so they aim toward that goal as well. Historically, accounting education has prepared students to perform stage 1- and stage 2-type work.

Boom! This is compelling evidence. It might not mean that the profession has abandoned accounting completely. But it does mean that whatever they do, they simply don't care about it. Accounting, and its cousin Audits are loss-leaders for the other stuff, and eyes are firmly fixed on other, higher things. We might call the other stuff Consulting, and we might wonder at the correlation: consulting activities have consumed the major audit firms. There are no major audit firms any more, there are major consulting firms, some of which seem to sport a vestigial audit capability.

Robert Elliot's message is, more or less, that the audit's fundamental purpose in life is to urge accountancy firms into higher stages. It therefore matters not what the quality (high?) is, nor what the original purpose is (delivering a report for reliance by the external stakeholder?). We might argue for example whether audit is Stage 2 or Stage 3. But we know that the auditor doesn't express his opinion to the company, directly, and knowledge is the essence of the value chain. By the rules, he maintains independence, his opinion is reserved for outsiders. So audit is limited to Stages 3 and below, by its definition.

Can you see a "stage 4,5 sales opportunity" here?

Or perhaps more on point, can you avoid it?

It is now very clear where the auditors are. They're not "on audit" but somewhere higher. Consulting. MBA territory. Stage 5, please! The question is not where the accounting profession wants to go today, because they already got there, yesterday. The financial crisis thesis is confirmed. Audits are very much part of our problem, even if they are the accounting profession's solution.

What is less clear is where are we, the business world? The clients, the users, the reliers of audit product? And perhaps the question for us really is, what are we going to do about it?

September 16, 2009

Talks I'd kill to attend....

I'm not sure why I ended up on this link ... but it was something very strange. And then I saw this:

I'm not sure why I ended up on this link ... but it was something very strange. And then I saw this:

"Null References: The Billion Dollar Mistake"

That resonated! So what's it about? Well, some dude named Tony Hoare says:

I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965. At that time, I was designing the first comprehensive type system for references in an object oriented language (ALGOL W). My goal was to ensure that all use of references should be absolutely safe, with checking performed automatically by the compiler. But I couldn't resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.

I'm in for some of that. Where do I sign?

It gets better! Hidden in there was an entire track of bad ideas! I'm in awe! Look at this:

"Standards are Great, but Standardisation is a Really Bad Idea"Standards arise from consensus between competitors signaling maturity in a marketplace. A good standard can ensure interoperability and assist portability, allowing the switching of suppliers. A widely adopted standard can create new markets, and impose useful constraints which in turn foster good design and innovation. Standards are great, and as the old joke goes, that's why we have so many of them!

If standards represent peace, then formal standardisation can be war! Dark, political, expensive and exclusive games played out between large vendors often behind closed doors. There are better ways to forge consensus and build agreements and the notion of a committee taking often a number of years to writing a specification, especially in the absence of implementation experience appears archaic in today's world of Agile methods, test driven development, open source, Wikis and other Web base collaborations.

When I die and go to heaven's conferences, that's what I want hear. But there's more!

"RPC and its Offspring: Convenient, Yet Fundamentally Flawed"... A fundamental goal of these and countless other similar technologies developed over the years was to shoehorn distributed systems programming into the local programming models so customary and convenient to the average developer, thereby hiding the difficult issues associated with distribution such as partial failure, availability and location issues, and consistency and synchronization problems. ....

The old abstract-away-the-net trick... yes, that one never works, but we'll throw it in for free.

But wait, there's MORE:

"Java enterprise application standards..."In the late 90's, the J2EE standard was greeted with much enthusiasm, as a legion of Java developers were looking to escape proprietary vendor lock-in and ill-conceived technologies and embrace a standard, expert-designed specification for building enterprise applications in Java.

Unfortunately, the results were mixed, and included expensive failures like CMP/BMP entity beans. History has shown that both committee-led standards and container-managed frameworks gave way to open source driven innovation and lightweight POJO-based frameworks.

oh, POJO, Oh, OH, PO JO! (Why am I thinking about that scene in _When Harry met Sally_?)

If you're a good software engineer (and all readers of this blog are *good* at something) you'll also appreciate this one:

"Traditional Programming Models: Stone knives and bearskins in the Google age"Programming has been taught using roughly the same approach for decades, but today's systems use radically different architectures -- consider the explosion in the count of processors and cores, massively distributed environments running parallel computations, and fully virtualized operating environments.

Learn how many of yesterday's programming principles have inadvertently become today's worst practices, and how these anti-patterns continue to form the basis of modern programming languages, frameworks and infrastructure software.

...

How come these guys have all the fun?

When and where is this assembly of net angels? Unlike Dave, I am not giving away tickets. Worse, you can't even pay for it with money. It's over! March 2009, and nobody knew. Who do I kill?

September 14, 2009

Audits V: Why did this happen to us ;-(

To summarise previous posts, what do we know? We know so far that the hallowed financial Audit doesn't seem to pick up impending financial disaster, on either a micro-level like Madoff (I) or a macro-level like the financial crisis (II). We also know we don't know anything about it (III), trying harder didn't work (II), and in all probability the problem with Audit is systemic (IV). That is, likely all of them, the system of Audits, not any particular one. The financial crisis tells us that.

To summarise previous posts, what do we know? We know so far that the hallowed financial Audit doesn't seem to pick up impending financial disaster, on either a micro-level like Madoff (I) or a macro-level like the financial crisis (II). We also know we don't know anything about it (III), trying harder didn't work (II), and in all probability the problem with Audit is systemic (IV). That is, likely all of them, the system of Audits, not any particular one. The financial crisis tells us that.

Notwithstanding its great brand, Audit does not deliver. How could this happen? Why did our glowing vision of Audit turn out to be our worst nightmare? Global financial collapse, trillions lost, entire economies wallowing in the mud and slime of bankruptcy shame?

Let me establish the answer to this by means of several claims.

First, complexity . Consider what audit firm Ernst & Young told us a while back:

The economic crisis has exposed inherent weaknesses in the risk management practices of banks, but few have a well-defined vision of how to tackle the problems, according to a study by Ernst & Young.Of 48 senior executives from 36 major banks around the world questioned by Ernst & Young, just 14% say they have a consolidated view of risk across their organisation. Organisational silos, decentralisation of resources and decision-making, inadequate forecasting, and lack of transparent reporting were all cited as major barriers to effective enterprise-wide risk management.

The point highlighted above is this: This situation is complex! In essence, the process is too complex for anyone to appreciate from the outside. I don't think this point is so controversial, but the next are.

My second claim is that in any situation, stakeholders work to improve their own position . To see this, think about the stakeholders you work with. Examine every decision that they take. In general, every decision that reduces the benefit to them will be fiercely resisted, and any decision that increases the benefit to them will be fiercely supported. Consider what competing audit firm KPMG says:

A new study put out by KPMG, an audit, tax and advisory firm said that pressure to do "whatever it takes" to achieve business goals continues as the primary driver behind corporate fraud and misconduct.Of more than 5,000 U.S. workers polled this summer, 74 percent said they had personally observed misconduct within their organizations during the prior 12 months, unchanged from the level reported by KPMG survey respondents in 2005. Roughly half (46 percent) of respondents reported that what they observed "could cause a significant loss of public trust if discovered," a figure that rises to 60 percent among employees working in the banking and finance industry.

This is human nature, right? It happens, and it happens more than we like to admit. I suggest it is the core and prime influence, and won't bother to argue it further, although if you are unsatisfied at this claim, I suggest you read Lewis on The End (warning it's long).

As we are dealing with complexity, even insiders will not find it easy to identify the nominal, original benefit to end-users. And, if the insiders can't identify the benefit, they can't put it above their own benefit. Claims one and two, added together, give us claim three: over time, all the benefit will be transferred from the end-users to the insiders . Inevitably. And, it is done naturally, subconciously and legally.

What does this mean to Audits? Well, Auditors cannot change this situation. If anything, they might make it worse. Consider these issues:

- the Auditor is retained by the company,

- to investigate a company secret,

- the examination, the notes, the results and concerns are all secret,

- the process and the learning of audit work is surrounded by mystique and control in classical guild fashion,

- the Auditor bills-per-hour,

- the Auditor knows what the problems are,

- and has integral consulting resources attached,

- who can be introduced to solve the problems,

- and bill-per-hour.

As against all that complexity and all that secrecy, there is a single Auditor, delivering a single report. To you. A rather single very small report, as against a rather frequent and in sum, huge series of bills.

So in all this complexity, although the Audit might suggest that they can reduce the complexity by means of compressing it all into one single "opinion", the complexity actually works to the ultimate benefit of the Auditor. Not to your benefit. It is to the Auditor's advantage to increase the complexity, and because it is all secret and you don't understand it anyway, any negative benefit to you is not observable. Given our second claim, this is indeed what they do.

Say hello to SOX, a doubling of the complexity, and a doubling of your auditor's invoice.Say thank you, Congressmen Sarbanes and Oxley, and we hope your pension survives!

Claim Number 4: The Auditor has become the insider. Although he is the one you perceive to be an outsider, protecting your interests, in reality, the Auditor is only a nominal, pretend outsider. He is in reality a stakeholder who was given the keys to become an insider a long time ago. Is there any surprise that, with the passage of time, the profession has moved to secure its role? As stakeholder? As insider? To secure the benefit to itself?

Over time, the noble profession of Auditing has moved against your interests. Once, it was a mighty independent observer, a white knight riding forth to save your honour, your interest, your very patrimony. Audits were penetrating and meticulous!

Now, the auditor is just another incumbent stakeholder, another mercenary for hire. Test this: did any audit firm fight the rise of Sarbanes-Oxley as being unnecessary, overly costly and not delivering value for money to clients? Does any audit firm promote a product that halves the price? Halves the complexity? Has any audit firm investigated the relationship between the failed banks and the failed audits over those banks? Did any audit firm suggest that reserves weren't up to a downturn? Has any audit firm complained that mark-to-market depends on a market? Did any auditor insist on stress testing? Has ... oh never mind.

I'm honestly interested in this question. If you know the answer: posted it in comments! With luck, we can change the flow of this entire research, which awaits ... the NEXT post.

September 11, 2009

40 years on, packets still echo on, and we're still dropping the auth-shuns

It's terrifically cliched to say it these days, but the net is one of the great engineering marvels of science. The Economist reports it as 40 years old:

Such contentious issues never dawned on the dozen or so engineers who gathered in the laboratory of Leonard Kleinrock (pictured below) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) on September 2nd, 1969, to watch two computers transmit data from one to the other through a 15-foot cable. The success heralded the start of ARPANET, a telecommunications network designed to link researchers around America who were working on projects for the Pentagon. ARPANET, conceived and paid for by the defence department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (nowadays called DARPA), was unquestionably the most important of the pioneering “packet-switched” networks that were to give birth eventually to the internet.

Right, ARPA funded a network, and out of that emerged the net we know today. Bottom-up, not top-down like the European competitor, OSI/ISO. Still, it wasn't about doing everything from the bottom:

The missing link was supplied by Robert Kahn of DARPA and Vinton Cerf at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. Their solution for getting networks that used different ways of transmitting data to work together was simply to remove the software built into the network for checking whether packets had actually been transmitted—and give that responsibility to software running on the sending and receiving computers instead. With this approach to “internetworking” (hence the term “internet), networks of one sort or another all became simply pieces of wire for carrying data. To packets of data squirted into them, the various networks all looked and behaved the same.

I hadn't realised that this lesson is so old, but that makes sense. It is a lesson that will echo through time, doomed to be re-learnt over and over again, because it is so uncomfortable: The application is responsible for getting the message across, not the infrastructure. To the extent that you make any lower layer responsible for your packets, you reduce reliability.

This subtlety -- knowing what you could push down into the lower layers, and what you cannot -- is probably one of those things that separates the real engineers from the journeymen. The wolves from the sheep, the financial cryptographers from the Personal-Home-Pagers. If you thought TCP was reliable, you may count yourself amongst latter, the sheepish millions who believed in that myth, and partly got us to the security mess we are in today. (Related, it seems is that cloud computing has the same issue.)

Curiously, though, from the rosy eyed view of today, it is still possible to make the same layer mistake. Gunnar reported on the very same Vint Cerf saying today (more or less):

Internet Design Opportunities for ImprovementThere's a big Gov 2.0 summit going on, which I am not at but in the event apparently John Markoff asked Vint Cerf ths following question: "what would you have designed differently in building the Internet?" Cerf had one answer: "more authentication"

I don't think so. Authentication, or authorisation or any of those other shuns is again something that belongs in the application. We find it sits best at the very highest layer, because it is a claim of significant responsibility. At the intermediate layers you'll find lots of wannabe packages vying for your corporate bux:

* IP * IP Password * Kerberos * Mobile One Factor Unregistered * Mobile Two Factor Registered * Mobile One Factor Contract * Mobile Two Factor Contract * Password * Password Protected transport * Previous Session * Public Key X.509 * Public Key PGP * Public Key SPKI * Public Key XML Digital Signature * Smartcard * Smartcard PKI * Software PKI * Telephony * Telephony Nomadic * Telephony Personalized * Telephony Authenticated * Secure remote password * SSL/TLS Client Authentication * Time Sync Token * Unspecified

and that's just in SAML! "Holy protocol hodge-podge Batman! " says Gunnar, and he's not often wrong.

Indeed, as Adam pointed out, the net works in part because it deliberately shunned the auth:

The packet interconnect paper ("A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication," Vint Cerf and Robert Kahn) was published in 1974, and says "These associations need not involve the transmission of data prior to their formation and indeed two associates need not be able to determine that they are associates until they attempt to communicate."

So what was Vint Cerf getting at? He clarified in comments to Adam:

The point is that the current design does not have a standard way to authenticate the origin of email, the host you are talking to, the correctness of DNS responses, etc. Does this autonomous system have the authority to announce these addresses for routing purposes? Having standard tools and mechanisms for validating identity or authenticity in various contexts would have been helpful.

Right. The reason we don't have standard ways to do this is because it is too hard a problem. There is no answer to what it means:

people like me could and did give internet accounts to (1) anyone our boss said to and (2) anyone else who wanted them some of this internet stuff and wouldn't get us in too much trouble. (Hi S! Hi C!)

which therefore means, it is precisely and only whatever the application wants. Or, if your stack design goes up fully past layer 7 into the people layer, like CAcert.org, then it is what your boss wants. So, Skype has it, my digital cash has it, Lynn's X959 has it, and PGP has it. IPSec hasn't got it, SSL hasn't got it, and it looks like SAML won't be having it, in truck-loads :) Shame about that!

Digital signature technology can help here but just wasn't available at the time the TCP/IP protocol suite was being standardized in 1978.

(As Gunnar said: "Vint Cerf should let himself off the hook that he didn't solve this in 1978.") Yes, and digital signature technology is another reason why modern clients can be designed with it, built in and aligned to the application. But not "in the Internet" please! As soon as the auth stuff is standardised or turned into a building block, it has a terrible habit of turning into treacle. Messy brown sticky stuff that gets into everything, slows everyone down and gives young people an awful insecurity complex derived from pimples.

Oops, late addition of counter-evidence: "US Government to let citizens log in with OpenID and InfoCard?" You be the judge!

September 10, 2009

Hide & seek in the terrorist battle

Court cases often give us glimpses of security issues. A court in Britain has just convicted three from the liquid explosives gang, and now that it is over, there are press reports of the evidence. It looks now like the intelligence services achieved one of two possible victories by stopping the plot. Wired reports that NSA intercepts of emails have been entered in as evidence.

According to Channel 4, the NSA had previously shown the e-mails to their British counterparts, but refused to let prosecutors use the evidence in the first trial, because the agency didn’t want to tip off an alleged accomplice in Pakistan named Rashid Rauf that his e-mail was being monitored. U.S. intelligence agents said Rauf was al Qaeda’s director of European operations at the time and that the bomb plot was being directed by Rauf and others in Pakistan.The NSA later changed its mind and allowed the evidence to be introduced in the second trial, which was crucial to getting the jury conviction. Channel 4 suggests the NSA’s change of mind occurred after Rauf, a Briton born of Pakistani parents, was reportedly killed last year by a U.S. drone missile that struck a house where he was staying in northern Pakistan.

Although British prosecutors were eager to use the e-mails in their second trial against the three plotters, British courts prohibit the use of evidence obtained through interception. So last January, a U.S. court issued warrants directly to Yahoo to hand over the same correspondence.

So there are some barriers between intercept and use in trial. The reason they came from the NSA is probably that old trick of avoiding prohibitions on domestic surveillance: if the trial had been in the USA, GCHQ might have provided the intercepts.

What however was more interesting is the content of the alleged messages. This BBC article includes 7 of them, here's one:

4 July 2006: Abdulla Ahmed Ali to Pakistan Accused plotter Abdulla Ahmed AliListen dude, when is your mate gonna bring the projectors and the taxis to me? I got all my bits and bobs. Tell your mate to make sure the projectors and taxis are fully ready and proper I don't want my presentation messing up.

WHAT PROSECUTORS SAID IT MEANT Prosecutors said that projectors and taxis were code for knowledge and equipment because Ahmed Ali still needed some guidance. The word "presentation" could mean attack.

The others also have interesting use of code words, such as Calvin Klein aftershave for hydrogen peroxide (hair bleach). The use of such codes (as opposed to ciphers) is not new; historically they were well known. Code words tend not to be used now because ciphers cover more of the problem space, and once you know something of the activity, the listener can guess at the meanings.

In theory at least, and code words clearly didn't work to protect the liquid bombers. Worse for them, it probably made their conviction easier, because Muslims discussing the purchase of 4 litres of aftershave with other Mulsims in Pakistan seems very odd.

One remaining question was whether the plot would actually work. We all know that the airlines banned liquids because of this event. Many amateurs have opined that it is simply too hard to do liquid explosives. However, the BBC employed an expert to try it, and using what amounts to between half a litre to a liter of finished product, they got this result:

Certainly a dramatic explosion, enough to kill people within a few metres, and enough to blow a 2m hole in the fuselage. (The BBC video is only a minute long, well worth watching.)

Would this have brought down the aircraft? Not necessarily as there are many examples of airlines with such damage that have survived. Perhaps if the bomb was in a strategic spot (over wing? or near the fuel lines?) or the aircraft was stuck over the Atlantic with no easy vector. Either way, a bad day to fly, and as the explosives guy said, pity the passengers that didn't have their seat belt on.

Score one for the intel agencies. But the terrorists still achieved their second victory out of two: passengers are still terrorised in their millions when they forget to dispose of their innocent drinking water. What is somewhat of a surprise is that the terrorists have not as yet seized on the disruptive path that is clearly available, a la John Robb. I read somewhere that it only takes a 7% "security tax" on a city to destroy it over time, and we already know that the airport security tax has to be in that ballpark.

"

dc:creator="iang"

dc:date="2009-09-05T15:16:45-05:00" />

-->

A month ago, the crypto-tea rooms were buzzing about the result in AES-256. Apparently, now weaker than AES-128. Can it be? Well, at first I thought this was impossible, because the cryptographers were not panicking, they were simply admiring the result. But the numbers that were reported indicated a drop in attack complexity to below AES-128, and the world was lapping it up. So, a week back I got a chance to ask Dani Nagy of epointsystem.org, a real cryptographer, what the story is. Here it is. I've edited it for flow & style, but hopefully it unfolds like the original conversation: Another attack was blogged by Bruce Schneier on July 30, 2009 and published on August 3, 2009. This new attack, by Alex Biryukov, Orr Dunkelman, Nathan Keller, Dmitry Khovratovich, and Adi Shamir, is against AES-256 that uses only two related keys and 2^39 time to recover the complete 256-bit key of a 9-round version, or 2^45 time for a 10-round version with a stronger type of related subkey attack, or 2^70 time for a 11-round version. 256-bit AES uses 14 rounds, so these attacks aren't effective against full AES. Dani: I agree with Scheier's assessment. Moreover, I think that AES-256 is no pareto-improvement over AES-128 (which is what I always use), and has all sorts of additional costs that are not justified. On the other hand, 32-bit optimized implementation of AES-128 are faster than RC4, which is absolutely amazing, IMHO. Dani: The abstract of the Biryukov-Khorvatovich paper does not give any quantitative description of the result about AES-128 ... Dani: Oh, it's actually from 2^256 to 2^119 indeed for a first key recovery! And here, outside our normal programme, is news from RAH that people pay for the privilege of being a suicide bomber: It's important to examine security models remote to our own, because it it gives us neutral lessons on how the economics effects the result. An odd comparison there, that number $1088 is about the value required to acquire a good-but-false set of identity documents. Gunnar reports that someone called Robert Garigue died last month. This person I knew not, but his model resonates. Sound bites only from Gunnar's post: ...First, they miss the opportunity to look at security as a business enabler. Dr. Garigue pointed out that because cars have brakes, we can drive faster. Security as a business enabler should absolutely be the starting point for enterprise information security programs. Secondly, if your security model reflects some CYA abstraction of reality instead of reality itself your security model is flawed. I explored this endemic myopia... This rhymes with: "what's your business model?" The bit lacking from most orientations is the enabler, why are we here in the first place? It's not to show the most elegant protocol for achieving C-I-A (confidentiality, integrity, authenticity), but to promote the business. How do we do that? Well, most technologists don't understand the business, let alone can speak the language. And, the business folks can't speak the techno-crypto blah blah either, so the blame is fairly shared. Dr. Garigue points us to Charlemagne as a better model: He set up other schools, opening them to peasant boys as well as nobles. Charlemagne never stopped studying. He brought an English monk, Alcuin, and other scholars to his court - encouraging the development of a standard script. He set up money standards to encourage commerce, tried to build a Rhine-Danube canal, and urged better farming methods. He especially worked to spread education and Christianity in every class of people. He relied on Counts, Margraves and Missi Domini to help him. Margraves - Guard the frontier districts of the empire. Margraves retained, within their own jurisdictions, the authority of dukes in the feudal arm of the empire. Missi Domini - Messengers of the King. In other words, the role of the security person is to enable others to learn, not to do, nor to critique, nor to design. In more specific terms, the goal is to bring the team to a better standard, and a better mix of security and business. Garigue's mandate for IT security? How to know today tomorrow’s unknown ? How to structure information security processes in an organization so as to identify and address the NEXT categories of risks ? Curious, isn't it! But if we think about how reactive most security thinking is these days, one has to wonder where we would ever get the chance to fight tomorrow's war, today?September 05, 2009

What-the-heck happened to AES-256?

Iang: btw ... did you follow the recent AES-256 news?

Dani: No. What happened?

Iang: There is a related key attack on AES-256 that apparently it reduces its strength to something *less* than AES-128

Dani: Do you have a reference?

Iang:

On July 1, 2009, Bruce Schneier blogged about a related-key attack on the 192-bit and 256-bit versions of AES discovered by Alex Biryukov and Dmitry Khovratovich; the related key attack on the 256-bit version of AES exploits AES' somewhat simple key schedule and has a complexity of 2^119. This is a follow-up to an attack discovered earlier in 2009 by Alex Biryukov, Dmitry Khovratovich, and Ivica Nikolic, with a complexity of 2^96 for one out of every 2^35 keys.

Iang: OK. What I don't follow is, has the attack reduced the complexity of attacking AES-256 down from o(128) *OR* o(256) ? or alternatively, what is the brute force order of magnitude complexity of each of the algorithms?

Iang: The (3rd attack) abstract mentions:

However, AES-192 and AES-256 were recently shown to be breakable by attacks which require $2^{176}$ and $2^{119}$ time, respectively.

Abstract. In this paper we present two related-key attacks on the full AES. For AES-256 we show the first key recovery attack that works for all the keys and has complexity 2119 , while the recent attack by Biryukov-Khovratovich-Nikoli´c works for a weak key class and has higher complexity. The second attack is the first cryptanalysis of the full AES- 192. Both our attacks are boomerang attacks, which are based on the recent idea of finding local collisions in block ciphers and enhanced with the boomerang switching techniques to gain free rounds in the middle.

Iang: that's the implication ... a massive drop in orders of magnitude ... people are saying that with this attack, AES-256 is now weaker than AES-128 !

Dani: That's not entirely true, because it's also the space complexity (you need a database that long), while brute-forcing AES-128 has a space complexity of 1 key (the one being tried). For example, at my lab, we can manage a time complexity of 2^56, but we have nowhere near that amount of space.

Iang: hmmm.... so one part of the attack is down to 2^119 which space complexity is still 2^256?

Dani: No, the space complexity is also 2^119. But that's huge.

Dani: (the space complexity cannot be greater than time complexity, btw)

Iang: AES-128 has its 128 bit key ... so its space complexity is ... 2^128 ?

Dani: No, it's space complexity is 1.

Dani: You don't need pre-computed tables at all to brute-force it. When brute-forcing, you try one key at a time, 2^128 times.

Iang: Ah! (lightbulb) So AES-256 had time complexity of 2^256 and space complexity of 1, being the one brute forced key. Now, under this new attack, it has a time complexity of 2^119 and a space complexity of 2^119?

Dani: Yes, Time of 2^256 down to both time and space of 2^119.

Iang: Hmmm... so maybe that is why nobody reported the real comparison. So it is strictly not true to say AES-128 is now stronger than AES-256

Dani: It all depends on the time-space tradeoff one has to make. AES-128 is time-complexity of 2^128, and space complexity of 1. Is that stronger or weaker than 2^119 and 2^119?

Dani: But it seems true that AES-256 is strictly weaker than AES-192. The immediate practical implication is that it is even less worth bothering with larger AES keys than before. AES-128 is so much cheaper than the other two.

Iang: This explains the advice I have seen: "use AES-128"

Dani: But I would advise using AES-128 even without any weaknesses found. It is several times faster and more handy with both 32-bit and 64-bit architectures than the other two, without opening new practical avenues of attack even for the most powerful of adversaries.

Iang: Sounds good to me, especially as I chose it in my last crypto project :)

Iang: thanks for the clarification ... the real message was not easy to figure out from the press reports, and the abstract was cunningly written to cast in the best light, as always.

Dani: Thanks for the heads-up! Interesting developments and well-written papers.

September 04, 2009

Numbers: CAPTCHAs and Suicide Bombers

Two hard numbers effecting the attack model. The cost of attacking a CAPTCHA system with people in developing regions, from the Economist's report on the state of the CAPTCHA nation:

Two hard numbers effecting the attack model. The cost of attacking a CAPTCHA system with people in developing regions, from the Economist's report on the state of the CAPTCHA nation:The biggest flaw with all CAPTCHA systems is that they are, by definition, susceptible to attack by humans who are paid to solve them. Teams of people based in developing countries can be hired online for $3 per 1,000 CAPTCHAs solved. Several forums exist both to offer such services and parcel out jobs. But not all attackers are willing to pay even this small sum; whether it is worth doing so depends on how much revenue their activities bring in. “If the benefit a spammer is getting from obtaining an e-mail account is less than $3 per 1,000, then CAPTCHA is doing a perfect job,” says Dr von Ahn.

A second analysis with Palantir uncovered more details of the Syrian networks, including profiles of their top coordinators, which led analysts to conclude there wasn't one Syrian network, but many. Analysts identified key facilitators, how much they charged people who wanted to become suicide bombers, and where many of the fighters came from. Fighters from Saudi Arabia, for example, paid the most -- $1,088 -- for the opportunity to become suicide bombers.

September 02, 2009

Robert Garigue and Charlemagne as a model of infosec

"It's the End of the CISO As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)"...

...

King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor; conqueror of the Lombards and Saxons (742-814) - reunited much of Europe after the Dark Ages.

Knowledge of risky things is of strategic value