November 15, 2015

the Satoshi effect - Bitcoin paper success against the academic review system

One of the things that has clearly outlined the dilemma for the academic community is that papers that are self-published or "informally published" to borrow a slur from the inclusion market are making some headway, at least if the Bitcoin paper is a guide to go by.

Here's a quick straw poll checking a year's worth of papers. In the narrow field of financial cryptography, I trawled through FC conference proceedings in 2009, WEIS 2009. For Cryptology in general I added Crypto 2009. I used google scholar to report direct citations, and checked what I'd found against Citeseer (I also added the number of citations for the top citer in rightmost column, as an additional check. You can mostly ignore that number.) I came across Wang et al's paper from 2005 on SHA1, and a few others from the early 2000s and added them for comparison - I'm unsure what other crypto papers are as big in the 2000s.

| Conf | paper | Google Scholar | Citeseer | top derivative citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| jMLR 2003 | Latent dirichlet allocation | 12788 | 2634 | 26202 |

| NIPS 2004 | MapReduce: simplified data processing on large clusters | 15444 | 2023 | 14179 |

| CACM 1981 | Untraceable electronic mail, return addresses, and digital pseudonyms | 4521 | 1397 | 3734 |

| self | Security without identification: transaction systems to make Big Brother obsolete | 1780 | 470 | 2217 |

| Crypto 2005 | Finding collisions in the full SHA-1 | 1504 | 196 | 886 |

| SIGKDD 2009 | The WEKA data mining software: an update | 9726 | 704 | 3099 |

| STOC 2009 | Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices | 1923 | 324 | 770 |

| self | Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system | 804 | 57 | 202 |

| Crypto09 | Dual System Encryption: Realizing Fully Secure IBE and HIBE under Simple Assumptions | 445 | 59 | 549 |

| Crypto09 | Fast Cryptographic Primitives and Circular-Secure Encryption Based on Hard Learning Problems | 223 | 42 | 485 |

| Crypto09 | Distinguisher and Related-Key Attack on the Full AES-256 | 232 | 29 | 278 |

| FC09 | Secure multiparty computation goes live | 191 | 25 | 172 |

| WEIS 2009 | The privacy jungle: On the market for data protection in social networks | 186 | 18 | 221 |

| FC09 | Private intersection of certified sets | 84 | 24 | 180 |

| FC09 | Passwords: If We’re So Smart, Why Are We Still Using Them? | 89 | 16 | 322 |

| WEIS 2009 | Nobody Sells Gold for the Price of Silver: Dishonesty, Uncertainty and the Underground Economy | 82 | 24 | 275 |

| FC09 | Optimised to Fail: Card Readers for Online Banking | 80 | 24 | 226 |

What can we conclude? Within the general infosec/security/crypto field in 2009, the Bitcoin paper is the second paper after Fully homomorphic encryption (which is probably not even in use?). If one includes all CS papers in 2009, then it's likely pushed down a 100 or so slots according to citeseer although I didn't run that test.

If we go back in time there are many more influential papers by citations, but there's a clear need for time. There may well be others I've missed, but so far we're looking at one of a very small handful of very significant papers at least in the cryptocurrency world.

It would be curious if we could measure the impact of self-publication on citations - but I don't see a way to do that as yet.

February 04, 2013

Deviant Identity - Facebook and the One True Account

From Facebook:

The company identifies three types of accounts that don’t represent actual users: duplicate accounts, misclassified accounts and undesirable accounts. Together, they added up to just over 7 percent of its worldwide monthly active users last year.Facebook disclosed the figures in its annual report filed with the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission on Friday.

Duplicate accounts, or those maintained by people in addition to their principal account, represent 53 million accounts, or 5 percent of the total, Facebook said.

Misclassified accounts, including those created for non-human entities such as pets or organizations, which instead should have Facebook Pages, accounted for almost 14 million accounts, or 1.3 percent of the total.

And undesirable accounts, such as those created by spammers, rounded out the tally with 9.5 million accounts, or 0.9 percent of users.

Context - systems that maintain user accounts and expect each account to map universally and uniquely to one person and only only person are in for a surprise -- people don't do that. The experience from CAcert is that even with a system that is practically only there for the purpose of mapping a human, for certificates attesting to some aspect of their Identity, there are a host of reasons why some people have multiple accounts. And most of those are good reasons, including ones laid at the door of the system provider.

There is no One True Account, just as there is no One True Name or One True Identity. Nor are there any One True Statistics, but what we have can help.

September 01, 2010

profound misunderstandability in your employee's psyche

Speaking of profound misunderstandings, this:

BitDefender created a "test profile" of a nonexistent, 21-year-old woman described as a "fair-haired" and "very, very naïve interlocutor" -- basically a hot rube who was just trying to "figure out how this whole social networking thing worked" by asking a bunch of seemingly innocent, fact-finding questions.With the avatar created, the fictitious person then sent out 2,000 "friendship requests," relying on the bogus description and made-up interests as the presumptive lure. Of the 2,000 social networks pinged with a "friendship" request, a stunning 1,872 accepted the invitation. And the vast majority (81 percent) of them did it without asking any questions at all. Others asked a question or two, presumably like, "Who are you?" or "How do I know you?" before eventually adding this new "friend."

...

But it gets worse. An astonishing 86 percent of those who accepted the bogus profile's "friendship" request identified themselves as working in the IT industry. Even worse, 31 percent said they worked in some capacity in IT security.

December 05, 2009

Phishing numbers

From a couple of sources posted by Lynn:

- A single run only hits 0.0005 percent of users,

- 1% of customers will follow the phishing links.

- 0.5% of customers fall for phishing schemes and compromise their online banking information.

- the monetary losses could range between $2.4 million and $9.4 million annually per one million online banking clients

- in average ... approximately 832 a year ... reached users' inboxes.

- costs estimated at up to $9.4 million per year per million users.

- based on data colleded from "3 million e-banking users who are customers of 10 sizeable U.S. and European banks."

The primary source was a survey run by an anti-phishing software vendor, so caveats apply. Still interesting!

For more meat on the bigger picture, see this article: Ending the PCI Blame Game. Which reads like a compressed version of this blog! Perhaps, finally, the thing that is staring the financial operators in the face has started to hit home, and they are really ready to sound the alarm.

November 26, 2009

Breaches not as disclosed as much as we had hoped

One of the brief positive spots in the last decade was the California bill to make breaches of data disclosed to effected customers. It took a while, but in 2005 the flood gates opened. Now reports the FBI:

"Of the thousands of cases that we've investigated, the public knows about a handful," said Shawn Henry, assistant director for the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Cyber Division. "There are million-dollar cases that nobody knows about."

That seems to point at a super-iceberg. To some extent this is expected, because companies will search out new methods to bypass the intent of the disclosure laws. And also there is the underlying economics. As has been pointed out by many (or perhaps not many but at least me) the reputation damage probably dwarfs the actual or measurable direct losses to the company and its customers.

Companies that are victims of cybercrime are reluctant to come forward out of fear the publicity will hurt their reputations, scare away customers and hurt profits. Sometimes they don't report the crimes to the FBI at all. In other cases they wait so long that it is tough to track down evidence.

So, avoidance of disclosure is the strategy for all properly managed companies, because they are required to manage the assets of their shareholders to the best interests of the shareholders. If you want a more dedicated treatment leading to this conclusion, have a look at "the market for silver bullets" paper.

Meanwhile, the FBI reports that the big companies have improved their security somewhat, so the attackers direct at smaller companies. And:

Meanwhile, the FBI reports that the big companies have improved their security somewhat, so the attackers direct at smaller companies. And:

They also target corporate executives and other wealthy public figures who it is relatively easy to pursue using public records. The FBI pursues such cases, though they are rarely made public.

Huh. And this outstanding coordinated attack:

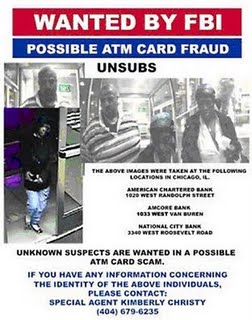

A similar approach was used in a scheme that defrauded the Royal Bank of Scotland's (RBS.L: Quote, Profile, Research, Stock Buzz) RBS WorldPay of more than $9 million. A group, which included people from Estonia, Russia and Moldova, has been indicted for compromising the data encryption used by RBS WorldPay, one of the leading payment processing businesses globally.The ring was accused of hacking data for payroll debit cards, which enable employees to withdraw their salaries from automated teller machines. More than $9 million was withdrawn in less than 12 hours from more than 2,100 ATMs around the world, the Justice Department has said.

2,100 ATMs! worldwide! That leaves that USA gang looking somewhat kindergarten, with only 50 ATMs cities. No doubt about it, we're now talking serious networked crime, and I'm not referring to the Internet but the network of collaborating, economic agents.

Compromising the data encryption, even. Anyone know the specs? These are important numbers. Did I miss this story, or does it prove the FBI's point?

January 19, 2009

Microsoft: Phishing losses greatly over-estimated

09 Jan 2009 14:21Phishers make much less from their scams than analysts have estimated, according to research from the software maker. The financial losses experienced by victims of phishing scams may be up to 50 times less than estimated by analysts, according to a Microsoft study. Previous studies by organisations such as Gartner, which in 2007 estimated US phishing losses at $3.2bn (£2bn), "crumble upon inspection", Microsoft researchers said in their report, published on Tuesday.

Nevertheless, stories of easy money may be encouraging a phishing "gold rush" effect, where large numbers of newcomers enter the phishing business expecting huge returns, only to be preyed upon by more experienced phishers, according to A Profitless Endeavor: Phishing as Tragedy of the Commons.

The study, undertaken by Microsoft researchers Cormac Herley and Dinei Florencio, also suggests there is less profit than thought in phishing because there is only a limited number of people who will be fooled by the scams, and that pool gets smaller as the scams claim victims.

"Phishing is a classic example of tragedy of the commons, where there is open access to a resource that has limited ability to regenerate," the authors say in their report. "Since each phisher independently seeks to maximise his return, the resource is over-grazed and [on average] yields far less than it is capable of." Instead of getting a maximum return for a minimum effort, the majority of phishers make a weekly wage of hundreds, rather than thousands, of dollars, the researchers said.

....

No comment from here, because I haven't read the source as yet.

April 17, 2008

Browser news: Fake subpoenas, the OODA waltz, and baby steps on the client side

Phishing still works, says Verisign:

...these latest messages masquerade as an official subpoena requiring the recipient to appear before a federal grand jury. The emails correctly address CEOs and other high-ranking executives by their full name and include their phone number and company name, according to Matt Richard, director of rapid response at iDefense, a division of VeriSign that helps protect financial institutions from fraud. ...About 2,000 executives took the bait on Monday, and an additional 70 have fallen for the latest scam, Richard said. Operating under the assumption that as many as 10 percent of recipients fell for the ruse, he estimated that 21,000 executives may have received the email. Only eight of the top 35 anti-virus products detected the malware on Monday, and on Wednesday, only 11 programs were flagging the new payload, which has been modified to further evade being caught.

I find 10% to be exceptionally large, but, OK, it's a number, and we collect numbers!

Disclosure for them: Verisign sells an an anti-phishing technology called secure browsing, or at least the certificates part of that. (Hence they and you are interested in phishing statistics.) Due to problems in the browser interface, they and other CAs now also sell a "green" version called Extended Validation. This -- encouragingly -- fixes some problems with the older status quo, because more info is visible for users to assess risks (a statement by the CA, more or less). Less encouragingly, EV may trade future security for current benefit, because it further cements the institutional structure of secure browsing, meaning that as attackers spin faster in their OODA loops, browsers will spin slower around the attackers.

Luckily, Johnath reports that further experiments are due in Firefox 3.1, so there is still some spinning going on:

Here’s my initial list of the 3 things I care most about, what have I missed?1. Key Continuity Management

Key continuity management is the name for an approach to SSL certificates that focuses more on “is this the same site I saw last time?” instead of “is this site presenting a cert from a trusted third party?” Those approaches don’t have to be mutually exclusive, and shouldn’t in our case, but supporting some version of this would let us deal more intelligently with crypto environments that don’t use CA-issued certificates.

Jonath's description sells it short, perhaps for political reasons. KCM is useful when the user knows more than the CA, which unfortunately is most of the time. This might mean that the old solution should be thrown out in favour of KCM, but the challenge lies in extracting the user's knowledge in an efficacious way. As the goal with modern software is to never bother the user then this is much more of a challenge than might be first thought. Hence, as he suggests, KCM and CA-certified browsing will probably live side by side for some time.

If there was a list of important security fixes for phishing, I'd say it should be this: UI fixes, KCM and TLS/SNI. Firefox is now covering all three of those bases. Curiously, Johnath goes on to say:

The first is for me to get a better understanding of user certificates. In North America (outside of the military, at least) client certificates are not a regular matter of course for most users, but in other parts of the world, they are becoming downright commonplace. As I understand it, Belgium and Denmark already issue certs to their citizenry for government interaction, and I think Britain is considering its options as well. We’ve fixed some bugs in that UI in Firefox 3, but I think it’s still a second-class UI in terms of the attention it has gotten, and making it awesome would probably help a lot of users in the countries that use them. If you have experience and feedback here, I would welcome it.

Certainly it is worthy of attention (although I'm surprised about the European situation) because they strictly dominate over username-passwords in such utterly scientific, fair and unbiased tests like the menace of the chocolate bar. More clearly, if you are worried about eavesdropping defeating your otherwise naked and vulnerable transactions, client-side private keys are the start of the way forward to proper financial cryptography.

I've found x.509 client certificates easier to use than expected, but they are terribly hard to install into the browser. There are two real easy fixes for this: 1. allow the browser to generate a self-signed cert as a default, so we get more widespread use, and 2. create some sort of CA <--> browser protocol so that this interchange can happen with a button push. (Possible 3., I suspect there may be some issues with SSL and client certs, but I keep getting that part wrong so I'll be vague this time!)

Which leaves us inevitably and scarily to our other big concern: Browser hardening against MITB. (How that is done is ... er ... beyond scope of a blog post.) What news there?

- related: Safari fixes released.

April 19, 2006

Numbers on British Fraud and Debt

A list of numbers on fraud, allegedly from The Times (also) repeated here FTR (for the record).

| Regular credit card number: | $1 |

| Credit card with 3-digit security code: | $3-$5 |

| Credit card with code and PIN: | $10-$100 |

| Social security number (US): | $5-$10 |

| Mother's maiden name: | $5-$10 |

THE BIG NUMBERS

£56.4 ($100) billion: Total amount owed on British credit cards 141.1 million: Number of credit, debit and charge cards in Britain 1.9 billion: Number of purchases on credit and charge cards in Britain a year £123 billion: Total value of credit and charge card purchases a year 5: Number of credit, debit and charge cards held by 1 in 10 consumers £58: Average value of a purchase on a credit card £41: Average value of a debit card purchase 88 percent: Proportion of applicants who have been issued with a credit card without providing proof of income £504.8 ($895) million: Total plastic-card fraud losses on British cards a year £1.3 ($2.3) million: Amount of fraud committed against cards each day 7: Number of seconds between instances of fraud £696 ($1,235): Average size of fraud, 2004

(Printing them in USD is odd, but there you go... I've preferred the Times' UKP amounts above, as there were a number of mismatches.)

April 18, 2006

Voting and more from the Red Queen

Cubicle points to a great article that contrasts voting machines with gambling machines.

It's easier to rig an electronic voting machine than a Las Vegas slot machine, says University of Pennsylvania visiting professor Steve Freeman. That's because Vegas slots are better monitored and regulated than America's voting machines.

Of course the gambling machines come out on top - they are more carefully governed because the nature of the money is very very clear. With a voting machine, you the punter has no clear picture of how it is being used to reach into your pocket, and your natural skepticism is swept aside by airy fairy claims of democracy and honesty of our public process blah blah.

In contrast to that rosy view of gambling governance, Risks points out that:

Casino can reprogram slot machines in seconds <"Peter G. Neumann"> Wed, 12 Apr 2006 11:10:27 PDTAs an enormous operational improvement, the 1,790 slot machines in Las Vegas's Treasure Island Casino can now be reprogrammed in about 20 seconds from the back-office computer. Previously this was an expensive manual operation that required replacing the chip and the glass display in each machine. Now it is even possible to have different displays for different customers, e.g., changing between "older players and regulars" during the day and a different crowd at night ("younger tourists and people with bigger budgets". (Slot machines generate more than $7B revenue annually in Nevada.) Casinos are also experimenting with chips having digital tags that can be used to profile bettors, and wireless devices that would enable players to gamble while gamboling (e.g., in swimming pools!). [Source: Article by Matt Richtel, Prefer Oranges to Cherries? Done! *The New York Times*, 12 Apr 2006, C1,C4; PGN-ed]

Well, the WaPo story was nice while it lasted. More from Risks, there are reports that votes of lesser importance were interfered with. Going to the sources:

Washington voting hijacked by computer mischiefAn online poll asking Washingtonians to pick their favorite design for the state's quarter coin was suspended, after the balloting was hijacked by computer programs whose automated scripts pushed the tally past 1 million votes over the weekend. State officials overseeing the balloting originally decided not to limit the number of votes coming from individual computers so that family members sharing a single machine could each cast a vote, Gerth said. But that philosophy was being abandoned after the weekend's voting, which showed some computers casting repeated votes for a quarter design faster than humanly possible.

[Source: Associated Press item, seen in *The Seattle Times*, 12 Apr 2006; PGN-ed]

DoIT Information on ASM Election IssuesMore specifically, DoIT detected a disparity between the number of student votes cast and the number of votes confirmed in the online election database. In the Student Council portion of the election, 94 more ballots were cast than were posted; in the referenda portion, 436 more ballots were cast than posted. After further investigation today, DoIT determined that there were no additional discrepancies in the referenda

I wrote before on the monetary aspects of voting. The first story above is about money, but it hardly seems monetary. The second is more of a political issue - but such polls often lead to power and money.

The question then arises if in any voting system it is unreasonable to assume 'honest' behaviour, even if the poll is over issues of no direct importance? Is it therefore better to assume that in any voting system, some small group of users will manipulate if given the chance? Even if there is no benefit to them?

The system of voting I wrote about last week solved this problem -- in the face of prior efforts to increase unimportant ratings fraudulently -- by checking identity on handing out the tokens. That's pretty boring. But if we decide that the only solution to proper democracy is a strong identity society, there's an awful lot of waste there, not to mention risk of identity abuse.

April 09, 2006

Votes are coins stamped with the Red Queen's head

In FC we know voting as a sort of constrained monetary auction. Indeed, some wit said political elections are just an advance auction of stolen goods. The spirit of democracy is an inspiring thing, and it suggests to many that we should be able to solve all our problems democractically, no? Well, no. Least of all money, but this doesn't stop some from trying.

I was recently coralled into becoming a sort of elections officer in a vote on funding applications. There was some large bickies to allocate to a needy public, and the story is worth recording, so here goes.

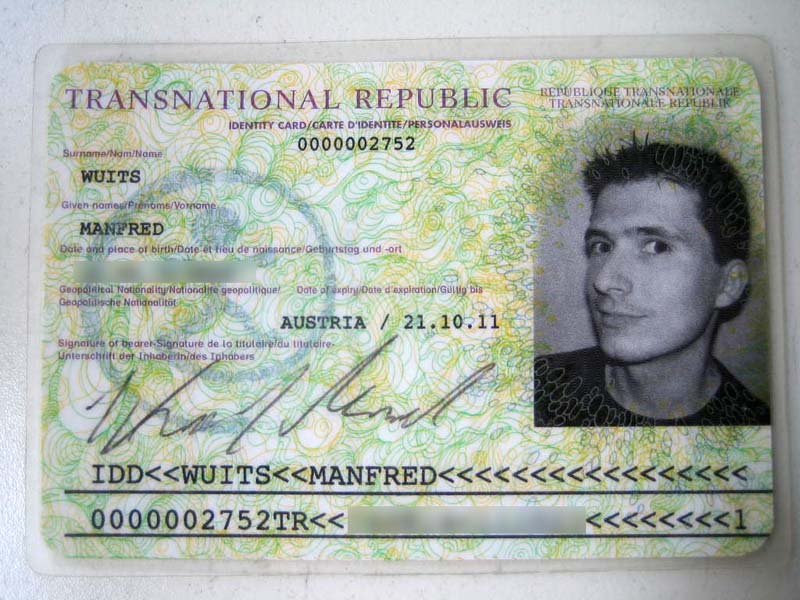

Grantees were encouraged to present their proposals before the body politic. Each person in the community was given a quantity of peanuts. These weren't the rooty / fruity kind, but pieces of paper saying "In Peanuts we Trust!" My job, alongside half a dozen others, was to verify the identity of people by checking their government-issued Identity docs, record the vital statistics, and hand over 70 peanuts to each person.

Standards on identity were curious. It had to have a photo. So credit cards did not count, but Manfred's above was accepted. If someone had not registered, all officers had to vote by show of hands to let them in. If they had no Id, then they had to find a mutual friend to vouch for them; someone who we knew, that knew them.

Why so serious? Because in a recent vote, several groups had cheated to push the rankings of their projects up the ladder! Why did they do that? Because they could, because it was art, because it was free like beer. So this time, the less amused among the community were taking no chances, it seemed.

At 21 hours, the bell rang and the issue of peanuts was over. (Luckily, the beer and some mighty fine broccali soup was still flowing.) Some 30 or so project groups had a brief 30 minutes to collect votes from each other. This phase exhibited one major flaw in that there was no anonymity - project marketeers running around with envelopes were able to employ a gamut of social pressures to secure their peanuts, and smaller, less marketing-savvy projects suffered.

While this was going on, we back in the issuance room were madly collating and cross-checking to validate the total issued peanuts.

| Number of voters: | 169 |

| Total Peanuts: | 70 * 169 == 11830 |

| Cost to Issue: | (2 days * 1 for printing) + (3 hours * 6 for issuance) |

| Value of Peanut: | 4.22 |

In order to make the voting serious, groups were given a limit - each group had to exceed a low watermark and not exceed a high watermark. This was to stop large projects dominating and small projects diminishing, or something.

So when the scores were announced, the obvious thing happened - projects that were below the low watermark ran around and grouped up into larger projects. Or, they sold their peanuts for promises of funds to other projects. And projects over the high watermark did the same thing! Meanwhile, over at the bar, all night there had been a ready cash market for peanuts. The first trades were observed at 7, and finally settled at 2, which is indicative of quite good estimating by the market.

Which means that the peanuts were money, but shackled with the inefficiency an imposed spirit of democracy. Quite a common suffering these days, it seems. A more ideal distribution system is then to simply give all people the peanuts as money, and instead of encouraging some notion of voting, encourage as many transactions as possible. Perhaps the rule is that there are 3 rounds, all transactions are anonymous and nobody gets to see their total at any time? When it finally settles, the hope would be that the decisions have best reflected the voice of the market.

This mirrors recent results in the economics of privatisation. In disbursing the value of communist assets such as factories, mines, etc, those newly freed countries in Eastern Europe that moved fastest benefitted more quickly. The end results indicated that speed, efficiency, and certainty paid off, even at the expense of some hypothetical losses to those who "missed out."

The vote got the whole thing over with in one evening, and I find comfortable parallel with recent results in the economics of privatisation. In disbursing the value of communist assets such as factories, mines, etc, those newly freed countries in Eastern Europe that moved fastest benefitted most, and more quickly. The end results indicated that speed, efficiency, and certainty paid off, even at the expense of some hypothetical losses to those who "missed out."

From the pov of the grantor, then, it has to be judged a fast, efficient and certain success. Now everyone knows -- a valuable thing.

August 03, 2005

The Phishing Borg - now absorbing IM, spam, viruses, lawyers, courts and you

Dramatic increase in threats to IM (instant messaging or chat) seen as the IMLogic Threat Center reports a 28 times increase over the last year.

Right on cue. Meanwhile, new tool to download for your browser shows that independent researchers at Stanford know where to put the protection: Spoofguard detects and warns against phishing, and PwdHash augments the password calculation to make each transmitted password site-dependent.

Good stuff guys! We need to induct you into the anti-fraud coffee room before you get swallowed up by the anti-borg of secret committees in smoke-filled rooms.

And in Korea is looking to legalise class-action suits in cases where small losses make it uneconomic for victims to punish negligent providers.

Much as I wonder if class action suits aren't a net loss to society and shouldn't be treated within the threat model rather than the security model, they do seem to be the only non-technical defence that suppliers will listen to. Such suits and others by regulators are filed against data providers (and losers), banks and Microsoft on various causes. Nobody has yet pinned one directly on phishing, but I give it a better than evens chance that it will be tried on the banks, and then on the software suppliers.

Although it is hard to decipher, a new report from IBM reports that spam is down from 83% of all email to 67% in June. That's the "good news." The bad news is that it's almost certainly because phishing and viruses have skyrocketed even this year, with IBM reporting that phishing has now reached around 20% and viruses around 4% of all email. The article is ridiculously muddled in its use of numbers, but I make that around a 91% garbage rate in email.

This to my mind confirms predictions made here that phishing is still the #1 threat to email (by value!), browsing and Internet commerce; viruses are now economically being driven by phishing; and email is dying under the one-two punch of spam and phishing.

Is phishing and related fraud becoming the #1 threat to the net, or is it already there?

June 23, 2004

Phishing I - Penny Black leads to Billion Dollar Loss

Today, the Financial Times leads its InfoTech review with phishing [1]. The FT has new stats: Brightmail reports 25 unique phishing scams per day. Average amount shelled out for 62m emails by corporates that suffer: $500,000. And, 2.4bn emails seen by Brightmail per month - with a claim that they handle 20% of the world's mail. Let's work those figures...

That means 12bn emails per month are scams. If 62m emails cause costs of half a million, then that works out at $0.008 per email. 144bn emails per year makes for ... $1.152 billion dollars paid out every year [2].

In other words, each phishing email is generating losses to business of a penny. Black indeed - nobody has been able to show such a profit model from email, so we can pretty much guarantee that the flood is only just beginning.

(The rest of the article included lots of cartels trying to peddle solutions, and a mention that the IETF things email authentication might help. Fat chance of that, but it did mention one worrying development - phishers are starting to use viral techniques to infect the user's PC with key loggers. That's a very worrying development - as there is no way a program can defeat something that is permitted to invade by the Microsoft operating system.)

[1] The Financial Times, London, 23rd June 2004,

"Gone phishing," FT-IT Review.

[2] Compare and contrast this 1 billion dollar loss to the $5bn claimed by NYT last week:

"Phishing an epidemic, Browsers still snoozing"

http://www.financialcryptography.com/mt/archives/000153.html

Addendum 2004-07-17: One article reports that Phishing will cost financial firms $400m in 2004, and another article, Firms hit hard by identity theft reports:

"While it's difficult to pin down an exact dollar amount lost when identity thieves strike such institutions, Jones said 20 cases that have been proposed for federal prosecution involve $300,000 to $1 million in losses each."

This matches the amount reported in the Texas phishing case, although it refers to identity theft, not phishing (yes, they are not the same).

Addendum 2004-07-27: Amir Herzberg and Ahmad Gbara report in their draft paper :

A study by Gartner Research [L04] found that about two million users gave such information to spoofed web sites, and that "Direct losses from identity theft fraud against phishing attack victims -- including new-account, checking account and credit card account fraud" cost U.S. banks and credit card issuers about $1.2 billion last year.

[L04] Avivah Litan, Phishing Attack Victims Likely Targets for Identity Theft, Gartner FirstTake, FT-22-8873, Gartner Research, 4 May 2004

Addendum 2008-09-03 Fighting Phish, Fakes and Frauds talks about additional support calls costs and users who depart from ecommerce.

May 05, 2004

Cost of Phishing - Case in Texas

Below is the first quantitative estimate of costs for phishing that I have seen - one phisher took $75,000 from 400 victims. It's a number! What is needed now is a way to estimate what the MITM attack on secure browsing has done in terms of total damages across the net.

U.S. shuts down Internet 'phishing' scam

Monday, March 22, 2004 Posted: 3:59 PM EST (2059 GMT)

WASHINGTON (Reuters) -- The U.S. government said Monday it had arrested a Texas man who crafted fake e-mail messages to trick hundreds of Internet users into providing credit card numbers and other sensitive information.

Zachary Hill of Houston pleaded guilty to charges related to a "phishing" operation, in which he sent false emails purportedly from online businesses to collect sensitive personal information from consumers, the Federal Trade Commission said.

According to the FTC, Hill sent out official-looking e-mail notices warning America Online and Paypal users to update their accounts to avoid cancellation.

Those who clicked on a link in the message were directed to a Web site Hill set up that asked for Social Security numbers, mothers' maiden names, bank account numbers and other sensitive information, the FTC said.

Phishing has emerged as a favorite tool of identity thieves over the past several years and experts say it is a serious threat to consumers.

Hill used the information he collected to set up credit-card accounts and change information on existing accounts, the FTC said. He duped 400 users out of at least $75,000 before his operation was shut down December 4, FTC attorneys said.

Hill will be sentenced on May 17, according to court documents.

A lawyer for Hill was not immediately available for comment.

Scam artists have posed as banks, online businesses and even the U.S. government to gather personal information, setting up Web pages that closely mirror official sites.

FTC officials said consumers should never respond to an e-mail asking for sensitive information by clicking on a link in the message. "If you think the company needs your financial information, it's best to contact them directly," FTC attorney Lisa Hone said.

Those who believe they may be victims of identity theft should visit the FTC's Web site (www.consumer.gov/idtheft), she said.

America Online is a division of Time Warner Inc., as is CNN. Paypal is owned by eBay Inc.

Addendum: The FTC appears to have settled with Zachary. The amount phished is now set at $125k but is unrecovered. (This is over the *two* cases charged below, who appear to be the same case.)

"Phishers" Settle Federal Trade Commission Charges

Friday, June 18 2004 @ 06:17 AM Contributed by: ByteEnable

Operators who used deceptive spam and copycat Web sites to con consumers into turning over confidential financial information have agreed to settle Federal Trade Commission charges that their scam violated federal laws.

The two settlements announced today will bar the defendants from sending spam, bar them from making false claims to obtain consumers' financial information, bar them from misrepresenting themselves to consumers, and bar them from using, selling, or sharing any of the sensitive consumer information collected.

Based on financial records provided by the defendants, the FTC agreed to consider the $125,000 judgments in each case satisfied. If the court finds that the financial documents were falsified, however, the defendants will pay $125,000 in consumer redress. One of the defendants also faces 46 months in prison on criminal charges filed by the Justice Department.

The scam, called "phishing," worked like this: Posing as America Online, the con artists sent consumers e-mail messages claiming that there had been a problem with the billing of their AOL accounts. The e-mail warned consumers that if they did not update their billing information, they risked losing their accounts. The messages directed consumers to click on a hyperlink in the body of the e-mail to connect to the "AOL Billing Center." When consumers clicked on the link they landed on a site that contained AOL's logo, AOL's type style, AOL's colors, and links to real AOL Web pages. It appeared to be AOL's Billing Center. But it was not. The defendants had hijacked AOL's identity and used it to steal consumers' identities. The defendants ran a similar scam using the hijacked identity of PayPal.

The FTC charged the defendants with violating the FTC, which bars unfair and deceptive practices, and the Gramm Leach Bliley Act, which bars using false or fictitious statements to obtain consumers' financial information.

The settlements bar the defendants from sending spam for life. They bar the defendants from:

- Misrepresenting their affiliation with a consumer's ISP or online payment service provider;

- Misrepresenting that consumers' information needs to be updated;

- Using false "from" or "subject" lines; and

- Registering Web pages that misrepresent the host or sponsor of the page.

The settlements bar the defendants from making false, fictitious, or fraudulent statements to obtain financial information from consumers. They bar the defendants from using or sharing the sensitive information collected from consumers and require that all such information be turned over to the FTC. Financial judgments were stayed based on financial disclosure documents provided by the defendants showing they currently are unable to pay consumer redress. Should the court find that the financial disclosure documents were falsified, the defendants will be required to give up $125,000 in ill-gotten gains. The settlements contain standard record keeping provisions to allow the FTC to monitor compliance with the orders.

The defendant named in one of the complaints is Zachary Keith Hill. The Hill case was filed in December 2003, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas. The other case, filed in May 2004, charged an unnamed minor in U. S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York.

These cases were brought with the invaluable assistance of the Department of Justice Criminal Division's Computer Crimes and Intellectual Property Section, Federal Bureau of Investigation's Washington Field Office, and United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia's Computer Hacking and Intellectual Property Squad.

The Commission vote to accept the settlements was 5-0.

A newly revised FTC Consumer Alert, "How Not to Get Hooked by a 'Phishing' Scam" warns consumers who receive e-mail that claims an account will be shut down unless they reconfirm their billing information not to reply or click on the link in the e-mail. Consumers should contact the company that supposedly sent the message directly. More tips to avoid phishing scams can be found at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/pubs/alerts/phishingalrt.htm.

Consumers who believe they have been scammed by a phishing e-mail can file a complaint at http://www.ftc.gov, and then visit the FTC's Identity Theft Web site at www.consumer.gov/idtheft to learn how to minimize their risk of damage from ID theft. Consumers can also visit www.ftc.gov/spam to learn other ways to avoid e-mail scams and deal with deceptive spam.

NOTE: Stipulated final judgments and orders are for settlement purposes only and do not constitute an admission by the defendant of a law violation. Consent judgments have the force of law when signed by the judge.

Copies of the complaints and stipulated final judgments and orders are available from the FTC's Web site at http://www.ftc.gov and also from the FTC's Consumer Response Center, Room 130, 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20580. The FTC works for the consumer to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, and unfair business practices in the marketplace and to provide information to help consumers spot, stop, and avoid them. To file a complaint in English or Spanish (bilingual counselors are available to take complaints), or to get free information on any of 150 consumer topics, call toll-free, 1-877-FTC-HELP (1-877-382-4357), or use the complaint form at http://www.ftc.gov. The FTC enters Internet, telemarketing, identity theft, and other fraud-related complaints into Consumer Sentinel, a secure, online database available to hundreds of civil and criminal law enforcement agencies in the U.S. and abroad.