December 27, 2014

In-depth history: "SEALAND, HAVENCO, AND THE RULE OF LAW"

Graeme tips me to a fascinating in-depth review of the law aspects of Sealand and HavenCo, which makes essential reading for the libertarian / anarchist school of Internet entrepreneurialship:

SEALAND, HAVENCO, AND THE RULE OF LAW James GrimmelmannIn 2000, a group of American entrepreneurs moved to a former World War II antiaircraft platform in the North Sea, seven miles off the British coast. There, they launched HavenCo, one of the strangest start-ups in Internet history. A former pirate radio broadcaster, Roy Bates, had occupied the platform in the 1960s, moved his family aboard, and declared it to be the sovereign Principality of Sealand. HavenCo's founders were opposed to governmental censorship and control of the Internet; by putting computer servers on Sealand, they planned to create a "data haven" for unpopular speech, safely beyond the reach of any other country. This Article tells the full story of Sealand and HavenCo -- and examines what they have to tell us about the nature of the rule of law in the age of the Internet.

The story itself is fascinating enough: it includes pirate radio, shotguns, rampant copyright infringement, a Red Bull skateboarding special, perpetual motion machines, and the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of State. But its implications for the rule of law are even more remarkable. Previous scholars have seen HavenCo as a straightforward challenge to the rule of law: by threatening to undermine national authority, HavenCo was opposed to all law. As the fuller history shows, this story is too simplistic. HavenCo also depended on international law to recognize and protect Sealand, and on Sealand law to protect it from Sealand itself. Where others have seen HavenCo's failure as the triumph of traditional regulatory authorities over HavenCo, this Article argues that in a very real sense, HavenCo failed not from too much law but from too little. The "law" that was supposed to keep HavenCo safe was law only in a thin, formalistic sense, disconnected from the human institutions that make and enforce law. But without those institutions, law does not work, as HavenCo discovered.

(Disclosure: I knew the founders of HavenCo who were all at one time residing on CryptoHill in Anguilla.)

December 21, 2014

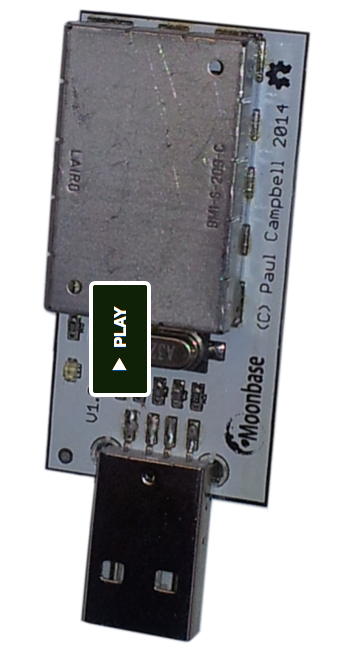

OneRNG -- open source design for your random numbers

Paul of Moonbase has put a plea onto kickstarter to fund a run of open RNGs. As we all know, having good random numbers is one of those devilishly tricky open problems in crypto. I'd encourage one and all to click and contribute.

Paul of Moonbase has put a plea onto kickstarter to fund a run of open RNGs. As we all know, having good random numbers is one of those devilishly tricky open problems in crypto. I'd encourage one and all to click and contribute.

For what it's worth, in my opinion, the issue of random numbers will remain devilish & perplexing until we seed hundreds of open designs across the universe and every hardware toy worth its salt also comes with its own open RNG, if only for the sheer embarrassment of not having done so before.

OneRNG is therefore massively welcome:

About this projectAfter Edward Snowden's recent revelations about how compromised our internet security has become some people have worried about whether the hardware we're using is compromised - is it? We honestly don't know, but like a lot of people we're worried about our privacy and security.

What we do know is that the NSA has corrupted some of the random number generators in the OpenSSL software we all use to access the internet, and has paid some large crypto vendors millions of dollars to make their software less secure. Some people say that they also intercept hardware during shipping to install spyware.

We believe it's time we took back ownership of the hardware we use day to day. This project is one small attempt to do that - OneRNG is an entropy generator, it makes long strings of random bits from two independent noise sources that can be used to seed your operating system's random number generator. This information is then used to create the secret keys you use when you access web sites, or use cryptography systems like SSH and PGP.

Openness is important, we're open sourcing our hardware design and our firmware, our board is even designed with a removable RF noise shield (a 'tin foil hat') so that you can check to make sure that the circuits that are inside are exactly the same as the circuits we build and sell. In order to make sure that our boards cannot be compromised during shipping we make sure that the internal firmware load is signed and cannot be spoofed.

OneRNG has already blasted through its ask of $10k. It's definitely still worth contributing more because it ensures a bigger run and helps much more attention on this project. As well, we signal to the world:

*we need good random numbers*

and we'll fight aka contribute to get them.

December 04, 2014

MITM watch - sitting in an English pub, get MITM'd

So, sitting in a pub idling till my 5pm, thought I'd do some quick check on my mail. Someone likes my post on yesterday's rare evidence of MITMs, posts a comment. Nice, I read all comments carefully to strip the spam, so, click click...

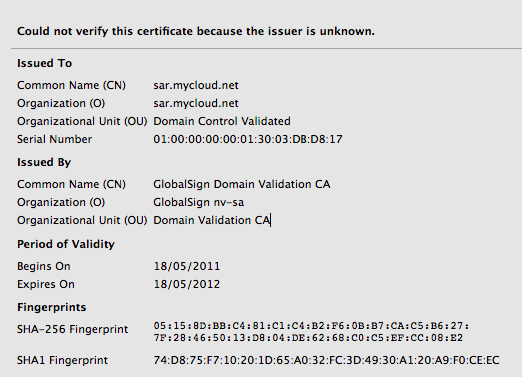

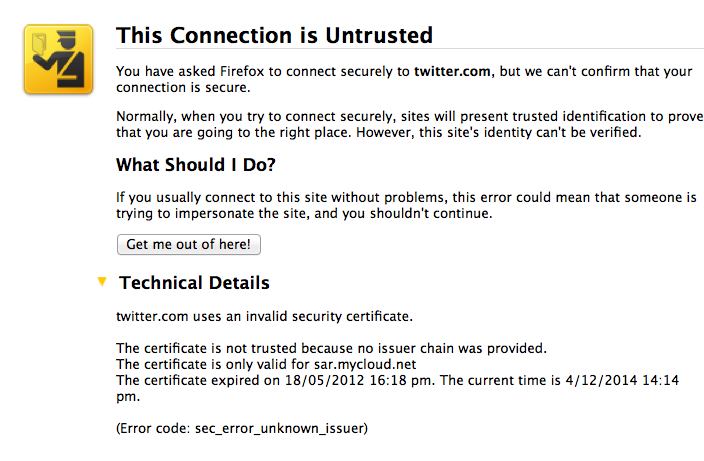

Boom, Firefox takes me through the wrestling trick known as MITM procedure. Once I've signalled my passivity to its immoral arrest of my innocent browsing down mainstreet, I'm staring at the charge sheet.

Whoops -- that's not financialcryptography.com's cert. I'm being MITM'd. For real!

Fully expecting an expiry or lost exception or etc, I'm shocked! I'm being MITM'd by the wireless here in the pub. Quick check on twitter.com who of course simply have to secure all the full tweetery against all enemies foreign and domestic and, same result. Tweets are being spied upon. The horror, the horror.

On reflection, the false positive result worked. One reason for that on the skeptical side is that, as I'm one of the 0.000001% of the planet that has wasted significant years on the business of protecting the planet against the MITM, otherwise known as the secure browsing model (queue in acronyms like CA, PKI, SSL here...), I know exactly what's going on.

How do I judge it all? I'm annoyed, disturbed, but still skeptical as to just how useful this system is. We always knew that it would pick up the false positive, that's how Mozilla designed their GUI -- overdoing their approach. As I intimated yesterday, the real problem is whether it works in the presence of a flood of false negatives -- claimed attacks that aren't really attacks, just normal errors and you should carry on.

Secondly, to ask: Why is a commercial process in a pub of all places taking the brazen step of MITMing innocent customers? My guess is that users don't care, don't notice, or their platforms are hiding the MITM from them. One assumes the pub knows why: the "free" service they are using is just raping their customers with a bit of secret datamining to sell and pillage.

Well, just another another data point in the war against the users' security.

December 03, 2014

MITM watch - patching binaries at Tor exit nodes

The real MITMs are so rare that protocols that are designed around them fall to the Bayesian impossibility syndrome (*). In short, false negatives cause the system to be ignored, and when the real negative indicator turns up it is treated as a false. Ignored. Fail.

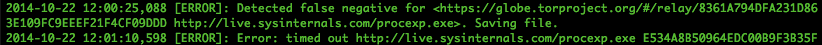

Here's some evidence of that with Tor:

... I tested BDFProxy against a number of binaries and update processes, including Microsoft Windows Automatic updates. The good news is that if an entity is actively patching Windows PE files for Windows Update, the update verification process detects it, and you will receive error code 0x80200053..... If you Google the error code, the official Microsoft response is troublesome.

If you follow the three steps from the official MS answer, two of those steps result in downloading and executing a MS 'Fixit' solution executable. ... If an adversary is currently patching binaries as you download them, these 'Fixit' executables will also be patched. Since the user, not the automatic update process, is initiating these downloads, these files are not automatically verified before execution as with Windows Update. In addition, these files need administrative privileges to execute, and they will execute the payload that was patched into the binary during download with those elevated privileges.

(*) I'd love to hear a better name than Bayesian impossibility syndrome, which I just made up. It's pretty important, it explains why the current SSL/PKI/CA MITM protection can never work, relying on Bayesian statistics to explain why infrequent real attacks cannot be defended against when overshadowed by frequent false negatives.