January 30, 2014

Hard Truths about the Hard Business of finding Hard Random Numbers

Editorial note: this rant was originally posted here but has now moved to a permanent home where it will be updated with new thoughts.

As many have noticed, there is now a permathread (Paul's term) on how to do random numbers. It's always been warm. Now the arguments are on solid simmer, raging on half a dozen cryptogroups, all thanks to the NSA and their infamous breach of NIST, American industry, mom's apple pie and the privacy of all things from Sunday school to Angry Birds.

Why is the topic of random numbers so bubbling, effervescent, unsatisfying? In short, because generators of same (RNGs), are *hard*. They are in practical experience trickier than most of the other modules we deal with: ciphers, HMACs, public key, protocols, etc.

Yet, we have come a long way. We now have a working theory. When Ada put together her RNG this last summer, it wasn't that hard. Out of our experience, herein is a collection of things we figured out; with the normal caveat that, even as RNs require stirring, the recipe for 'knowing' is also evolving.

- Use what your platform provides. Random numbers are hard, which is the first thing you have to remember, and always come back to. Random numbers are so hard, that you have to care a lot before you get involved. A hell of a lot. Which leads us to the following rules of thumb for RNG production.

- Use what your platform provides.

- Unless you really really care a lot, in which case, you have to write your own RNG.

- There isn't a lot of middle ground.

- So much so that for almost all purposes, and almost all users, Rule #1 is this: Use what your platform provides.

- When deciding to breach Rule #1, you need a compelling argument that your RNG delivers better results than the platform's. Without that compelling argument, your results are likely to be more random than the platform's system in every sense except the quality of the numbers.

- Software is our domain.

- Software is unreliable. It can be made reliable under bench conditions, but out in the field, any software of more than 1 component (always) has opportunities for failure. In practice, we're usually talking dozens or hundreds, so failure of another component is a solid possibility; a real threat.

- What about hardware RNGs? Eventually they have to go through some software, to be of any use. Although there are some narrow environments where there might be a pure hardware delivery, this is so exotic, and so alien to the reader here, that there is no point in considering it. Hardware serves software. Get used to it.

- As a practical reliability approach, we typically model every component as failing, and try and organise our design to carry on.

- Security is also our domain, which is to say we have real live attackers.

- Many of the sciences rest on a statistical model, which they can do in absence of any attackers. According to Bernoulli's law of big numbers, models of data will even out over time and quantity. In essence, we then can use statistics to derive strong predictions. If random numbers followed the law of big numbers, then measuring 1000 of them would tell us with near certainty that the machine was good for another 1000.

- In security, we live in a byzantine world, which means we have real live attackers who will turn our assumptions upside down, out of spite. When an attacker is trying to aggressively futz with your business, he will also futz with any assumptions and with any tests or protections you have that are based on those assumptions. Once attackers start getting their claws and bits in there, the assumption behind Bernoulli's law falls apart. In essence this rules out lazy reliance on statistics.

- No Test. There is no objective test of random numbers, because it is impossible to test for unpredictability. Which in practical terms means that you cannot easily write a test for it, nor can any test you write do the job you want it to do. This is the key unfortunate truth that separates RNs out from ciphers, etc (which latter are amenable to test vectors, and with vectors in hand, they become tractable).

- Entropy. Everyone talks about entropy so we must too, else your future RNG will exhibit the wrong sort of unpredictability. Sadly, entropy is not precisely the answer, enough such that talking about is likely missing the point. If we could collect it reliably, RNs would be easy. We can't so it isn't.

- Entropy is manifest physical energy, causing events which cannot be predicted using any known physical processes, by the laws of science. Here, we're typically talking about quantum energy, such as the unknown state of electrons, which can collapse either way into some measurable state, but it can only be known by measurement, and not predicted earlier. It's worth noting that quantum energy abounds inside chips and computers, but chips are designed to reduce the noise, not increase it, so turning chip entropy into RNs is not as easy as talking about it.

- There are objective statements we can make about entropy. The objective way to approach the collection of entropy is to carefully analyse the properties of the system and apply science to estimate the amount of (e.g.) quantum uncertainty one can derive from it. This is possible and instructive, and for a nice (deep) example of this, see John Denker's Turbid.

- At the level of implementation, objective statements about entropy fail for 2 reasons. Let's look at those, as understanding these limitations on objectivity is key to understanding why entropy does not serve us so willingly.

- Entropy can be objectively analysed as long as we do not have an attacker. An attacker can deliver a faulty device, can change the device, and can change the way the software deals with the device at the device driver level. And much more...

- This approach is complete if we have control of our environment. Of course, it is very easy to say Buy the XYZ RNG and plug it in. But many environments do not have that capability, often enough we don't know our environment, and the environment can break or be changed. Examples: rack servers lacking sound cards; phones; VMs; routers/firewalls; early startup on embedded hardware.

- In conclusion, entropy is too high a target to reach. We can reach it briefly, in controlled environments, but not enough to make it work for us. Not enough, given our limitations.

- CSRNs. The practical standard to reach therefore is what we call Cryptographically Secure Random Numbers.

- Cryptographically secure random numbers (or CSRNs) are numbers that are not predictable /to an attacker/. In contrast to entropy, we might be able to predict our CSRNs, but our enemies cannot. This is a strictly broader and easier definition than entropy, which is needed because collecting entropy is too hard, as above.

- Note our one big assumption here: that we can determine who is our attacker and keep him out, and determine who is friendly and let them in. This is a big flaw! But it happens to be a very basic and ever-present one in security, so while it exists, it is one we can readily work with.

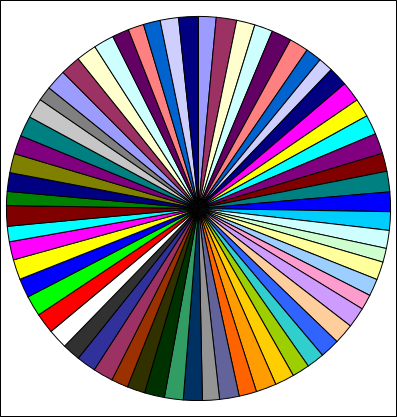

- Design. Many experiments and research seem to have settled on the following design pattern, which we call a Trident Design Pattern:

Entropy collector ----\

In short, many collectors of entropy feed their small contributions in to a Mixer, which uses the melded result to seed an Expander. The high level caller (application) uses this Expander to request her random numbers.

\ _____ _________ / \ / \

Entropy collector ---->( mixer )----->( expansion )-----> RNs

\_____/ \_________/

/

Entropy collector ----/ - Collectors. After all the above bad news, what is left in the software toolkit is: redundancy .

- A redundant approach tells us to draw our RNs from different places. The component that collects RNs from one place is called a Collector. Therefore we want many Collectors.

- Each of the many places should be uncorrelated with each other. If one of these were to fail, it would be unlikely that others also would fail, as they are uncorrelated. Typical studies of fault-tolerant systems often suggest the number 3 as the target.

-

Some common collector ideas are:

Some common collector ideas are:- the platform's own RNG, as a Collector into your RNG

- any CPU RNG such as Intel's RDRAND,

- measuring the difference between two uncorrelated clocks,

- timings and other measurands from events (e.g., mouse clicks and locations),

- available sensors (movement on phones),

- differences seen in incoming new business packets,

- a roughly protected external source such as a business feed,

- An attacker is assumed to be able to take a poke at one or two of these sources, but not all. If the attacker can futz with all our sources, this implies that he has more or less unlimited control over our entire machine. In which case, it's his machine, and not ours. We have bigger problems than RNs.

- We tend to want more numbers than fault-tolerant reliability suggests because we want to make it harder for the attacker. E.g., 6 would be a good target.

- Remember, we want maximum uncorrelation. Adding correlated collectors doesn't improve the numbers.

- Because we have redundancy, on a large scale, we are not that fussed about the quality of each Collector. Better to add another collector than improve the quality of one of them by 10%. This is an important benefit of redundancy, we don't have to be paranoid about the quality of this code.

- Mixer. Because we want the best and simplest result delivered to the caller, we have to take the output of all those above Collectors, mix them together, and deliver downstream.

- The Mixer is the trickiest part of it all. Here, you make or break. Here, you need to be paranoid. Careful. Seek more review.

- The Mixer has to provide some seed numbers of say 128-512 bits to the Expander (see below for rationale). It has to provide this on demand, quickly, without waiting around.

- There appear to be two favourite designs here: Push or Pull. In Push the collectors send their data directly into Mixer, forcing it to mix it in as it's pushed in. In contrast, a Pull design will have the Mixer asking the Collectors to provide what they have right now. This in short suggests that in a Push design the Mixer has to have a cache, while in Pull mode, the Collectors might be well served in having caches within themselves.

- Push or Mixer-Cache designs are probably more popular. See Yarrow and Fortuna as perhaps the best documented efforts.

- We wrote our recent Trident effort (AdazPRING) using Pull. The benefits include: simplified API as it is direct pull all the way through; no cache or thread in mixer; and as the Collectors better understand their own flow, so they better understand the need for caching and threading.

- Expander. Out of the Mixer comes some nice RNs, but not a lot. That's because good collectors are typically not firehoses but rather dribbles, and the Mixer can't improve on that, as, according to the law of thermodynamics, it is impossible to create entropy.

- The caller often wants a lot of RNs and doesn't want to wait around.

- To solve the mismatch between the Mixer output and the caller's needs, we create an expansion function or Expander. This function is pretty simple: (a) it takes a small seed and (b) turns that into a hugely long stream. It could be called the Firehose...

- Recalling our truth above of (c) CSRNs being the goal, not entropy, we now have a really easy solution to this problem: Use a cryptographic stream cipher. This black box takes a small seed (a-check!) and provides a near-infinite series of bytes (b-check!) that are cryptographically secure (c-check!). We don't care about the plaintext, but by the security claims behind the cipher, the stream is cryptographically unpredictable without access to the seed.

- Super easy: Any decent, modern, highly secure stream cipher is probably good for this application. Our current favourite is ChaCha20 but any of the NESSIE set would be fine.

- In summary, the Expander is simply this: when the application asks for a PRNG, we ask the Mixer for a seed, initialise a stream cipher with the seed, and return it back to the user. The caller sucks on the output of the stream cipher until she's had her fill!

- Subtleties.

- When a system first starts up there is often a shortage of easy entropy to collect. This can lead to catastrophic results if your app decides that it needs to generate high-value keys as soon as it starts up. This is a real problem -- scans of keys on the net have found significant numbers that are the same, which is generally traced to the restart problem. To solve this, either change the app (hard) ... or store some entropy for next time. How you do this is beyond scope.

- Then, assuming the above, the problem is that your attacker can do a halt, read off your RNG's state in some fashion, and then use it for nefarious purposes. This is especially a problem with VMs. We therefore set the goal that the current state of the RNG cannot be rolled forward nor backwards to predict prior or future uses. To deal with this, a good RNG will typically:

- stir fresh entropy into its cache(s) even if not required by the callers. This can be done (e.g.) by feeding ones own Expander's output in, or by setting a timer to poll the Collectors.

- Use hash whiteners between elements. Typically, a SHA digest or similar will be used to protect the state of a caching element as it passes its input to the next stage.

- As a technical design argument, the only objective way that you can show that your design is at least as good as or better than the platform-provided RNG is the following:

- Very careful review and testing of the software and design, and especially the Mixer; and

- including the platform's RNG as a Collector.

- Business Justifications.

As you can see, doing RNGs is hard! Rule #1 -- use what the platform provides. You shouldn't be doing this. About the only rationales for doing your own RNG are the following.

- Your application has something to do with money or journalism or anti-government protest or is a CVP. By money, we mean Bitcoin or other forms of hard digital cash, not online banking. The most common CVP or centralised vulnerability party (aka TTP or trusted third party) is the Certification Authority.

- Your operating platform is likely to be attacked by a persistent and aggressive attacker. This might be true if the platform is one of the following: any big American or government controlled software, Microsoft Windows, Java (code, not applets), any mobile phone OS, COTS routers/firewalls, virtual machines (VMs).

- You write your own application software, your own libraries *and* your own crypto!

- You can show objectively that you can do a better job.

That all said, good luck! Comments to the normal place, please, and Ed's note: this will improve in time.

January 22, 2014

Who invented the shared repository idea: Bitcoin, Boyle, and history

I had previously claimed that Todd Boyle had invented the idea of a shared transaction repository (or STR):

I had previously claimed that Todd Boyle had invented the idea of a shared transaction repository (or STR):

"BitCoin achieves the issuer part by creating a distributed and published database over clients that conspire to record the transactions reliably. The idea of publishing the repository to make it honest was initially explored in Todd Boyle's netledger design."

It was a point of some discord between us, and almost brought us to academic blows, but with the advent of Bitcoin and it's published, out-there, in-your-face ledger, now aka the blockchain, Todd's ideas have been cast in a new light.

This is a historical curiosity, and as I was challenged on this question by Luuk, a student of this history, I finally got around to researching it. Now, sadly, Todd has left the net scene for other things. But the wayback machine preserves his writings (GLT-GLR, STR and death to CDEA), and I found the following snippet concerning the GLT or General-Ledger-for-Transactions, his idea of a webserver that handled transactions for the world:

Triple entry accounting is this: You form a transaction in your [General-Ledger-for-Transactions]. Every GLT transaction requires naming an external party. ... [which names a] real customer or supplier ID which is publicly agreed, just as domain names or email addresses are part of public namespaces.When you POST, the entry is stored in your internal [GLT] just like in the past. But it is also submitted to the triple-entry table in whatever [Shared-Transaction-Repository] system you choose. Perhaps your own STR server, such as the STR module of your GL. Or perhaps it is a big STR server out at Exodus or your ISP or a BSP. The same information you stored in your GLT entry suffices to complete the shared entry in the STR, and your private Stub.

...

3. the GLT is something that is almost becoming a community asset. You just cannot get the kind of integrated economy we need, without some real consensus among practitioners, to move certain parts of the transaction to a shared place. I am not saying public; I am saying shared. The amount, date and description of a deal are inherently shared between two parties and should be stored visible to those two parties alone, i.e. either protected by private system permissions or, encrypted visible to those two parties alone.

For me, these paragraphs dating back to 2003 stake a tiny claim. I certainly don't claim the idea because I remain horrified at the privacy implications of a published general ledger, as expressed by Bitcoin, but that's something that the market has decided it's not so fussed about. What is interesting is that, rarely amongst contemporary writings, Marc Andreeson came out and said:

... Bitcoin at its most fundamental level is a breakthrough in computer science – one that builds on 20 years of research into cryptographic currency, and 40 years of research in cryptography, by thousands of researchers around the world.

Having been someone who started working in cryptographic currency in 1995, I'm very aware of the way this history unfolded. Satoshi Nakamoto stands on the shoulders of giants, his design is the very clever assembling of components that were tried beforehand, and found wanting for various reasons.

The notion of a public, and/or shared ledger is one of those components employed in Bitcoin, and for that, I think Todd deserves a small byline in history.

Todd Boyle! We who died in the entrepreneurial pursuit of digital currency, we salute you!

January 20, 2014

Digital Currencies get their mojo back: the Ripple protocol

I was pointed to Ripple and found it was actually a protocol (I thought it was a business, that's the trap with slick marketing). Worth a quick look. To my surprise, it was actually quite neat. However, tricks and traps abound, so this is a list of criticisms. I am hereby going to trash certain features of the protocol, but I'm trying to do it in the spirit of, please! Fix these things before it is too late. Been there, got the back-ache from the t-shirt made of chain mail. The cross you are building for yourself will be yours forever!

I was pointed to Ripple and found it was actually a protocol (I thought it was a business, that's the trap with slick marketing). Worth a quick look. To my surprise, it was actually quite neat. However, tricks and traps abound, so this is a list of criticisms. I am hereby going to trash certain features of the protocol, but I'm trying to do it in the spirit of, please! Fix these things before it is too late. Been there, got the back-ache from the t-shirt made of chain mail. The cross you are building for yourself will be yours forever!

Ripple's low level protocol layout is about what Gary Howland's SOX1 tried to look like, with more bells and whistles. Ripple is a protocol that tries to do the best of today's ideas that are around (with a nod towards Bitcoin), and this is one of its failings: It tries to stuff *everything* into it. Big mistake. Let's look at this with some choice elements.

Numbers: Here are the numbers it handles:

1: 16-bit unsigned integer

2: 32-bit unsigned integer

3: 64-bit unsigned integer

6: Currency Amount

16: 8-bit unsigned integer

17: 160-bit unsigned integer

Positive. One thing has been spotted and spotted well: in computing and networking we typically do not need negative numbers, and in the rare occasions we do, we can handle it with flags. Same with accounting. Good!

Now, the negatives.

First bad: Too many formats! It may not be clear to anyone doing this work de novo, but it is entirely clear to me now that I am in SOX3 - that is, the third generation of not only the basic formats but the suite of business objects - that the above is way too complicated.

x.509 and PGP formats had the same problem: too many encodings. Thinking about this, I've decided the core problem is historical and philosophical. The engineers doing the encodings are often highly adept at hardware, and often are seduced by the layouts in hardware. And they are often keen on saving every darn bit, which requires optimising the layout up the wazoo! Recall the old joke, sung to the Monty Python tune:

Every bit is great,

If a bit gets wasted,

God gets quite irate!

But this has all changed. Now we deal in software, and scripting languages have generally pointed the way here. In programming and especially in network layouts, we want *one number*, and that number has to cope with all we throw at it. So what we really want is a number that goes from 0 to infinity. Luckily we have that, from the old x.509/telco school. Here's a description taken from SDP1:

Compact Integer A Compact Integer is one that expands according to the size of the unsigned integer it carries. ...

A Compact Integer is formed from one to five bytes in sequence. If the leading (sign) bit in each byte is set, then additional bytes follow. If a byte has the sign bit reset (0) then this is the last byte. The unsigned integer is constructed by concatenating the lower order 7 bits in each byte.

A one byte Compact Integer holds an integer of 0 to 127 in the 7 lower order bits, with the sign bit reset to zero. A two byte Compact Integer can describe from 128 to 16383 (XXXX check). The leading byte has the sign bit set (1) and the trailing byte has the sign bit reset (0).

That's it (actually, it can be of infinite length, unlike the description above). Surprisingly, everything can be described in this. In the evolution of SOX, we started out with all the above fields listed by Ripple, and they all fell by the wayside. Now, all business objects use CompactInts, all the way through, for everything. Why? Hold onto that question, we'll come back to it...

Second bad: Let's look at Ripple's concept of currencies:

Native CurrencyNative amounts are indicated by the most-significant bit (0x8000000000000000) being clear. The remaining 63 bits represent a sign-and-magnitude integer. Positive amounts are encoded with the second highest bit (0x4000000000000000) set. The lower 62 bits denote the absolute value.

Ripple/IOU Currencies

Amounts of non-native currencies are indicated by the most-significant bit (0x8000000000000000) being set. They are encoded as a 64-bit raw amount followed by a 160-bit currency identifier followed by a 160-bit issuer. The issuer is always present, even if zero to indicate any issuer is acceptable.

The 64-bit raw amount is encoded with the most-significant bit set and the second most significant bit set if the raw amount is greater than zero. If the raw amount is zero, the remaining bits are zero. Otherwise, the remaining bits encode the mantissa (between 10^15 and 10^16-1) and exponent.

Boom! *Ripple puts semantics into low level syntax*. Of course, the result is a mess. Trying to pack too much business information into the layout has caused an explosion of edge cases.

What is going on here is that the architects of ripple protocol have not understood the power of OO. The notion of a currency is a business concept, not a layout. The packets that do things like transactions are best left to the business layer, and those packets will define what a currency amount means. And, they'll do it in the place where limits can be dealt with:

RationaleThe Ripple code uses a specialized internal and wire format to represent amounts of currency. Because the server code does not rely on a central authority, it can have no idea what ranges are sensible with currencies. In addition, it's handy to be able to use the same code both to handle currencies that have inflated to the point that you need billions of units to buy a loaf of bread and to handle currencies that have become extremely valuable and so extremely small amounts need to be tracked.

The design goals are:

Accuracy - 15 decimal digits

Wide representation range - 10^80 units of currency to 10^-80 units

Deterministic - no vague rounding by unspecified rules.

Fast - Integer math only.

(my emphasis) They have recognised the problems well. Now come back to that question: why does SOX3 use CompactInts everywhere? Because of the above Rationale. In the business object (recall, the power of OO) we can know things like "billions of units to buy a loaf of bread" and also get the high value ones into the same format.

Next bad: Contractual form. This team has spotted the conundrum of currency explosion, because that's the space they chose: everyone-an-issuer (as I termed it). Close:

Custom CurrenciesCurrency 160-bit identifier is the hash of the currency definition block, which is also its storage index. Contains: Domain of issuer. Issuer's account. Auditor's account (if any). Client display information. Hash of policy document.

So, using the hash leads to an infinite currency space, which is the way to handle it. Nice! Frequent readers know where I'm going with this: their currency definition block is a variation of the Ricardian Contract, in that it contains, amongst other things, a "Hash of the policy document."

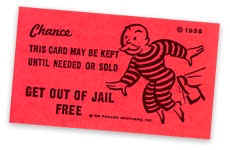

It's very close, it's almost a good! But it's not close enough. One of the subtleties of the Ricardian Contract is that because it put that information into the contract, *and not in some easily cached record*, it forced the following legal truth on the entire system: the user has the contract. Only with the presence of the contract can we now get access to data above, only with the presence of the contract can we even display to the user simple things like decimalisation. This statement -- the user has the contract -- is a deal changer for the legal stability of the business. This is your get out of jail free card in any dispute, and this subtle power should not be forgone for the mere technical benefit of data optimisation of cached blocks.

Next bad:

There are three types of currencies on ripple: ripple's native currency, also known as Ripples or XRP, fiat currencies and custom currencies. The later two are used to denominate IOUs on the ripple network.Native currency is handled by the absence of a currency indicator. If there is ever a case where a currency ID is needed, native currency will use all zero bits.

Custom currencies will use the 160-bit hash of their currency definition node as their ID. (The details have not been worked out yet.)

National currencies will be handled by a naming convention that species the three-letter currency code, a version (in case the currency is fundamentally changed), and a scaling factor. Currencies that differ only by a scaling factor can automatically be converted as transactions are processed. (So whole dollars and millionths of a penny can both be traded and inter-converted automatically.)

What's that about? I can understand the decision to impose one microcurrency into the protocol, but why a separate format? Why four separate formats? This is a millstone that the software will have to carry, a cost that will drag and drag.

There is no reason to believe that XRP or Natives or Nationals can be handled any differently from Customs. Indeed, the quality of the software demands that they be handled equivalently, the last thing you want is exceptions and multiple paths and easy optimisations. indeed, the concept of contracts demands it, and the false siren of the Nationals is just the journey you need to go on to understand what a contract is. A USD is not a greenback is not a self-issued dollar is not an petrodollar, and this:

Ripple has no particular support for any of the 3 letter currencies. Ripple requires its users to agree on meaning of these codes. In particular, the person trusting or accepting a balance of a particular currency from an issuer, must agree to the issuer's meaning.

is a cop-out. Luckily the solution is simple, scrap all the variations and just stick with the Custom.

Next: canonical layouts. Because this is a cryptographic payment system, in the way that only financial cryptographers understand, it is required that there be for every element and every object and every packet a single reliable canonical layout. (Yeah, so that rules out XML, JSON, PB, Java serialization etc. Sorry guys, it's that word: security!)

The short way to see this is signing packets. If you need to attach a digital signature, the recovery at the other end has to be bit-wise perfect because otherwise the digital signature fails.

We call this a canonical layout, because it is agreed and fixed between all. Now, it turns out that Ripple has a canonical layout: binary formats. This is Good. Especially, binary works far better with code, quality, networking, and canonicalisation.

But Ripple also has a non-canonical format: JSON. This is a waste of energy. It adds little benefit because you need the serialisation methods for both anyway, and the binary will always be of higher quality because of those more demanding needs mentioned above. I'd say this is a bad, although as I'm not aware of what they benefit they get from the JSON, I'll reserve judgement on that one.

Field Name Encodings -- good. This list recognises the tension for security coding. There needs to be a single place where all the tags are defined. I don't like it, but I haven't seen a better way to do this, and I think what we are seeing here in the Field Name Encodings' long list of business network objects is just that: the centralised definition of what format to expect to follow each tag.

Another quibble -- I don't see much mention of versions. In practice, business objects need them.

Penultimate point, if you're still with us. Let's talk layering. As is mooted above, the overall architecture of the Ripple protocol bundles the business information in with the low level packet stuff. In the same place as numbers, we also have currencies defined, digital signing and ledger items! That's just crazy. Small example, hashes:

4: 128-bit hash

5: 256-bit hash

And then there is the Currency hash of the contract information, which is a 160-bit encoding... Now, this is an unavoidable tension. The hash world won't stay still -- we started out with MACs of 32 bytes, then MD5 of 128 bits, SHA1 of 160 bits, and, important to realise, that SHA1 is deprecated, we now are faced with SHA2 in 4 different lengths, Keccak with variable length sponge function hashes, and emerging Polys of 64 bits.

Hashes won't sit still. I've also got in my work hash truncations of 48 bits or so, and pretend-hashes of 144 bits! Those latter are for internal float accounts for things like Chaumian blinded money (c.f., these days ZeroCoin).

So, Hashes are as much a business object decision as anything else. Hashes therefore need to be treated as locally designated but standardised units. Just setting hashes into the low layer protocol isn't the answer, you need a suite of higher level objects. The old principle of the one true cipher suite just doesn't work when it comes to hashes.

One final point. In general, it has to be stressed: in order to do network programming *efficiently* one has to move up the philosophical stack and utilise the power of Object Oriented Programming (used to be called OOP). Too many network protocols fall into a mess because they think OOP is an application choice, and they are at a lower place in the world. Not so; if there is anywhere that OOP makes a huge difference it is in network programming. If you're not doing it, you're probably costing yourself around 5 times the effort *and reducing your security and reliability*. That's at least according to some informal experiments I've run.

Ripple's not doing it, and this will strongly show in the altLang family.

(Note to self, must publish that Ouroboros paper which lays this out in more detail.)