December 29, 2013

The Ka-Ping challenge -- so you think you can spot a bug?

It being Christmas and we're all looking for a little fun, David Wagner has posted a challenge that was part of a serious study conducted by Ka-Ping Yee and himself:

Are you up to it? Are you a hacker-hero or a manager-mouse? David writes:

I believe I've managed to faithfully reconstruct the version of Ping's code that contains the deliberately inserted bug. If you would like to try your hand at finding the bug, you can look at it yourself:

http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~daw/tmp/pvote-backdoored.zip

I'm copying Ping, in case he wants to comment or add to this.

Some grounds rules that I'd request, if you want to try this on your own:

- Please don't post spoilers to the list. If you think you've found a bug, email Ping and David privately (off-list), and I'll be happy to confirm your find, but please don't post it to the list (just in case others want to take a look too).

- To help yourself avoid inadvertently coming across spoilers, please don't look at anything else on the web. Resist the temptation to Google for Pvote, check out the Pvote web site, or check out the links in the code. You should have everything you need in this email. We've made no attempt to conceal the details of the bug, so if you look at other resources on the web, you may come across other stuff that spoils the exercise.

- I hope you'll think of this as something for your own own personal entertainment and edification. We can't provide a controlled environment and we can't fully mimic the circumstances of the review over the Internet.

Here's some additional information that may help you.

We told reviewers that there exists at least one bug, in Navigator.py, in a region that contains 100 lines of code. I've marked the region using comments. So, you are free to focus on only that part of the code (I promise you that we did not deliberately insert any bug anywhere else outside that region). Of course, I'm providing all the code, because you may need to understand how it all interacts. The original Pvote code was written to be as secure and verifiable as we could make it; I'm giving you a modified version that was modified to add a bug after the fact. So, this is not some "obfuscated Python" contest where the entire thing was designed to conceal a malicious backdoor: it was designed to be secure, and we added a backdoor only as an afterthought, as a way to better understand the effectiveness of code review.

To help you conduct your code review, it might help to start by understanding the Pvote design. You can read about the theory, design, and principles behind Pvote in our published papers:

- An early version of Pvote, with many of the main ideas: paper: http://pvote.org/docs/evt2006/index.html Ping's slides: http://pvote.org/docs/evt2006/talk.pdf

- Many improvements to the initial idea, and the final Pvote: paper: http://pvote.org/docs/evt2007/index.html slides: http://pvote.org/docs/evt2007/talk.pdf

The Pvote code probably won't make sense without understanding some aspects of its design and how it is intended to be used, so this background material might be helpful to you.

We also gave reviewers an assurance document, which outlines the "assurance case" (a detailed argument describing why we believe Pvote is secure and fit for purpose and free of bugs). Here's most of it:

http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~daw/tmp/pvad-excerpts.pdf

Why not all of it? Because I'm lazy. The full assurance document contains the actual, unmodified Pvote code. We wrote the assurance document for the unmodified version of Pvote (without the deliberately inserted bug), and the full assurance document includes the code of the unmodified Pvote. If you were to look at that and compare it to the code I gave you above, you could quickly identify the bug by just doing a diff -- but that would completely defeat the purpose of the exercise. If I had copious free time, I'd modify the assurance document to give you a modified document that matches the modified code -- but I don't have time to do that. So, instead, I've just removed the part of the assurance document that contained the region of the code where we inserted our bug (namely, Navigator.py), and I'm giving you the rest of the assurance document.

In the actual review, we provided reviewers with additional resources that won't be available to you. For instance, we outlined for them the overall design principles of Pvote. We also were available to interactively answer questions, which helped them quickly get up to speed on the code. During the part where we had them review the modified Pvote with a bug inserted, we also answered their questions -- here's what Ping wrote about how we handled that part:

Since insider attacks are a major unaddressed threat in existing systems, we specifically wanted to experiment with this scenario. Therefore, we warned the reviewers to treat us as untrusted adversaries, and that we might not always tell the truth. However, since it was in everyone’s interest to use our limited time efficiently, we settled on a time-saving convention. We promised to truthfully answer any question about a factual matter that the reviewers could conceivably verify mechanically or by checking an independent source — for example, questions about the Python language, about static properties of the code, about its runtime behaviour, and so on.

Of course, since this is something you're doing on your own, you won't get the benefit of interacting with us and having us answer questions for you (to save you time). I realize this does make code review harder. My apologies.

You can assume that someone else has done some runtime testing of the code. We deliberately chose a bug that would survive "Logic & Accuracy Testing" (a common technique in elections, where election officials conduct a test in advance where they cast some ballots, typically chosen so that at least one vote has been cast for each candidate, and then check that the system accurately recorded and tallied those votes). Focus on code review.

-- David

December 24, 2013

MITB defences of dual channel -- the end of a good run?

Back in 2006 Philipp Gühring penned the story of what had been discovered in European banks, in what has now become a landmark paper in banking security:

A new threat is emerging that attacks browsers by means of trojan horses. The new breed of new trojan horses can modify the transactions on-the-fly, as they are formed in in browsers, and still display the user's intended transaction to her. Structurally they are a man-in-the-middle attack between the the user and the security mechanisms of the browser. Distinct from Phishing attacks which rely upon similar but fraudulent websites, these new attacks cannot be detected by the user at all, as they are use real services, the user is correctly logged-in as normal, and there is no difference to be seen.

This was quite scary. The European banks had successfully migrated their user bases across to the online platform and were well on the way to reducing branch numbers. Fantastic cost reductions... But:

The WYSIWYG concept of the browser is successfully broken. No advanced authentication method (PIN, TAN, iTAN, Client certificates, Secure-ID, SmartCards, Class3 Readers, OTP, ...) can defend against these attacks, because the attacks are working on the transaction level, not on the authentication level. PKI and other security measures are simply bypassed, and are therefore rendered obsolete.

If they saw any reduction in use of web banking, and the load shift back to branch, they were in a world of pain --- capacity had shrunk.

If they saw any reduction in use of web banking, and the load shift back to branch, they were in a world of pain --- capacity had shrunk.

The conclusion that the European banks came to, once they'd got over their initial fears, was that phones could be used to do SMS transaction authorisations. This system was rolled out over the next couple of years, and it more or less took the edge off the MITB.

Now comes news NSS Labs' Ken Baylor that the malware authors have developed two channel attacks:

On the positive side, there has been little innovation in the functionality of mobile financial malware in the last 24 months, and the iOS platform appears secure; however, further analysis reveals that there are now multiple mobile malware suites capable of defeating bank multifactor authentication. With 99 percent of new mobile malware targeting Android, attacks on this platform are unprecedented both in their number and their impact. The lack of iOS malware is likely related to the low availability of iOS malware developers in the ex-Soviet Republic.While banks remain slow to evolve their mobile security strategies, they will find the cyber criminals are several steps ahead of them.

Malware now tries to mount an attack on both channels. This occurs thus-ways:

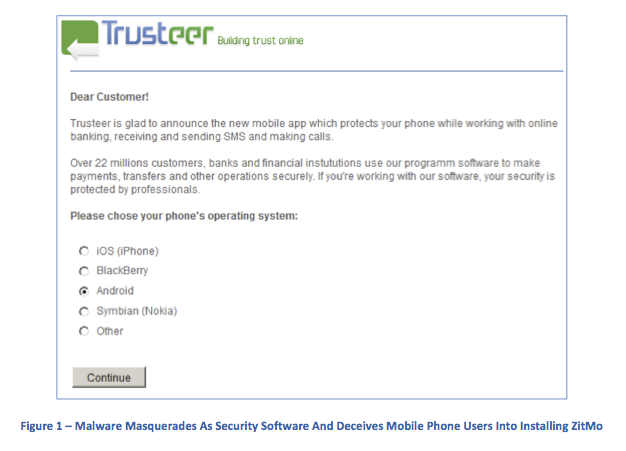

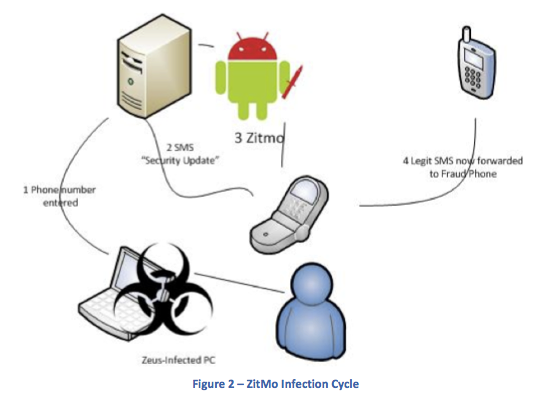

Zeus and other MITB trojans have used social engineering to bypass this process. When a user on an infected PC authenticates to a banking site using SMS authentication, the user is greeted by a webinject, similar to Figure 1. The webinject requires the installation of new software on the user’s mobile device; this software is in fact malware.ZitMo malware intercepts SMS TANs from the bank. Once greeted by the webinject on a Zeus-infected PC, the user enrolls by entering a phone number. A “security update” link is sent to the phone, and ZitMo installs when the link is clicked. Any bank SMS messages are redirected to a cyber criminal’s phone (all other SMS messages will be delivered as normal).

We knew at the time that this could occur, but it seemed unlikely. (I say 'we' to mean that I was mostly an observer; at the time I was in Vienna and was at the periphery of some of these groups. However, my lack of German made any contributions rather erratic.)

We knew at the time that this could occur, but it seemed unlikely. (I say 'we' to mean that I was mostly an observer; at the time I was in Vienna and was at the periphery of some of these groups. However, my lack of German made any contributions rather erratic.)

Unlikely because on the first hand it seemed an inordinate amount of complexity, and on the other, there wasn't enough of a target. What changed? The market has shifted hugely over to mobile use as opposed to web use. The Americans have been a bit slower, but now their on a roll:

According to the Pew Research Center,1 mobile banking usage has jumped from 24 percent of the US adult population in April 2012 to 35 percent in May 2013. Banks have encouraged this move toward mobile banking. Most banks began offering mobile services with a simple redirect to a mobile site (with limited functionality) upon detection of smartphone HTTP headers; others created mobile apps with HTML wrappers for a better user experience and more functionality. As yet, only a few have built secure native apps for each platform.Many banks believe that mobile devices are a secure secondary method of authentication. To authenticate the widest number of people who have phones (rather than just smartphones), many built their second factor authentication solutions on one of the most widely available (although insecure) protocols: short message services (SMS). As banks believed an SMS-authenticated customer was more secure than a PC-based user, they enabled the former to carry out riskier transactions. Realizing the rewards awaiting those able to circumvent SMS authentication, criminals quickly developed mobile malware.

So the convenient second channel of the phone has actually switched places: it's the primary channel, it's life, and the laptop is relegated to the at-office, at-home work slave. The model has been turned upside down, and in the things that fell out of the pockets, the security also took a tumble.

Closing with Ken Baylor's recommendations:

NSS Labs Recommendations

- Understand and account for current mobile malware strategies when developing mobile banking apps.

- Do not rely on SMS-based authentication; it has been thoroughly compromised.

- Retire HTML wrapper mobile banking apps and replace them with secure native mobile apps where feasible. These apps should include a combination of hardened browsers, certificate-based identification, unique install keys, in-app encryption, geolocation, and device fingerprinting.

Hey! I guess that's the business I'm in now. We've successfully ported the 'mature' Ricardo platform to Android: No flaky browsers in sight, and our auth strategy is a real strategy, not that old certificate-based snake-oil. Obviously, public keys and in-app encryption.

Geolocation and device fingerprinting I am yet to add. But that's easy enough later on. I guess I should post on all this some time, if anyone is interested...

December 23, 2013

We are all Satoshi Nakamoto

Rumours continue to circulate as to the person who wrote the Bitcoin paper. Occasionally they are directed at self, but they can equally be directed at all the superlative financial cryptographers listed on this site and many others.

Rumours continue to circulate as to the person who wrote the Bitcoin paper. Occasionally they are directed at self, but they can equally be directed at all the superlative financial cryptographers listed on this site and many others.

Let's take a moment to ask what we are doing here.

*Satoshi Nakamoto chose to do his work in anonymity*.

Or more technically in psuedoanonymity, as someone who claims to be 'anon' leaves no individual name and cannot be connected forward or backwards in time.

He, assuming it is a he, probably had good reasons for this. Which leaves us pondering why we would disrespect those reasons?

We, all of us, in today's Bitcoin world and yesterday's precursors to that world: cypherpunks, crypto, FC, privacy, mobile money, Tor, the Internet in general, ... we all hold privacy as an article of faith. We built the thing to protect people, and protect their privacy.

If Satoshi Nakamoto chose privacy, by what right or motive do we breach that? None.

There is no doctrine that permits anyone out there to arbitrarily strip out someone's privacy and remain one of us. Quite the opposite: our beliefs and existence call for protecting this person.

Indeed, revealing a stated secret of someone is more or less a crime in many contexts. Intelligence agencies can of course spy on whosoever, but they are not allowed to reveal that information (or, so says the doctrine). Police can demand information, but only pursuant to a crime -- probable cause and all that.

Freedom of the press? Public figures are by their nature afforded less 'privacy' because they are public; but they chose that path, and the courts grant the ability of the paparazzi only certain abilities, in line with the public figures' choice of public life. Paparazzi aren't allowed to chase ordinary folk, and Satoshi Nakamoto clearly chose to be out of that game.

Freedom of the press doesn't cut it. Nor does whistleblower status. Nor does 'public interest' as the public has no conceivable benefit to knowing more.

Those people who are digging around trying to strip this person's privacy are doing so because they haven't been called on it. Because they think it is cool. Because they feel intellectually challenged by the use of nyms, and using a nym is a licence to curiosity.

Wrong.

I call you now: what you are doing is wrong.

In some places it is a crime, because breaching privacy presumes there is another crime to follow: theft or fraud or extortion. It's a good presumption. In all civilised places, breaching privacy is an anathema. We all in this business -- save those sad damned souls with 5 eyes -- are working to *protect our community* not single out vulnerable persons and burn them at the stake.

Get you gone, get you out of our community. Anyone who publically reveals anyone else's private information has no common part with us. Anyone who goes on a witchhunt is our enemy. We are not doing all this work to give a few paparazzi a special scoop. To the person who eventually outs Satoshi Nakamoto I say this: the only place you'll be welcome is the NSA. Get ye there, scum.

In the words of that old film, we are all Satoshi Nakamoto.