November 21, 2010

What banking is. (Essential for predicting the end of finance as we know it.)

To understand what's happening today in the economy, we have to understand what banking is, and by that, I mean really understand how it works.

This time it's personal, right? Let's starts with what Niall Ferguson says about banking:

To understand why we have come so close to a rerun of the 1930s, we need to begin at the beginning, with banks and the money they make. From the Middle Ages until the mid-20th century, most banks made their money by maximizing the difference between the costs of their liabilities (payments to depositors) and the earnings on their assets (interest and commissions on loans). Some banks also made money by financing trade, discounting the commercial bills issued by merchants. Others issued and traded bonds and stocks, or dealt in commodities (especially precious metals). But the core business of banking was simple. It consisted, as the third Lord Rothschild pithily put it, "essentially of facilitating the movement of money from Point A, where it is, to Point B, where it is needed."

As much as the good Prof's comments are good and fruitful, we need more. Here's what banking really is:

Banking is borrowing from the public on demand, and lending those demand deposits to the public at term.

Sounds simple, right? No, it's not. Every one of those words is critically important, and change one or two of them and we've broken it. Let's walk it through:

Banking is borrowing from the public ..., and lending ... to the public.

Both from the public, and to the public. The public at both ends of banking is essential to ensure a diversification effect (A to B), a facilitation effect (bank as intermediary), and ultimately a public policy interest in regulation (the central bank). If one of those conditions aren't met, if one of those parties aren't "the public", then: it's not banking. For example,

- a building society or Savings & Loan is not doing banking, because .. it borrows from *members* who are by normal custom allowed to band together and do what they like with their money.

- a mutual fund is not banking because the lenders are sophisticated individuals, and the borrowers are generally sophisticated as well.

- Likewise, an investment bank does not deal with the public at all. So it's not banking. By this theory, it's really a financial investment house for savvy players (tell that to Deutschebank when it's chasing Goldman-Sachs for a missing billion...).

So now we can see that there is actually a reason why the Central Banks are concerned about banks, but less so about funds, S&Ls, etc. Back to the definition:

Banking is borrowing ... on demand, and lending those demand deposits ... at term.

On demand means you walk into the bank and get your money back. Sounds quite reasonable. At term means you don't. You have to wait until the term expires. Then you get your money back. Hopefully.

The bank has a demand obligation to the public lender, and a (long) term promise from the public borrower. This is quaintly called a maturity mismatch in the trade. What's with that?

The bank is stuck between a rock and a hard place. Let's put more meat on these bones: if the bank borrows today, on demand, and lends that out at term, then in the future, it is totally dependent on the economy being kind to the people owing the money. That's called risk, and for that, banks make money.

This might sound a bit dry, but Mervyn King, the Governor of the Bank of England, also recently took time to say it in even more dry terms (as spotted by Hasan):

3. The theory of bankingWhy are banks so risky? The starting point is that banks make heavy use of short-term debt. Short-term debt holders can always run if they start to have doubts about an institution. Equity holders and long-term debt holders cannot cut and run so easily. Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig showed nearly thirty years ago that this can create fragile institutions even in the absence of risk associated with the assets that a bank holds. All that is required is a cost to the liquidation of long-term assets and that banks serve customers on a first-come, first-served basis (Diamond and Dybvig, 1983).

This is not ordinary risk. For various important reasons, banking risk is extraordinary risk, because no bank, no matter where we are talking, can deal with unexpected risks that shift the economy against it. Which risks manifest themselves with an increase in defaults, that is, when the long term money doesn't come back at all.

Another view on this same problem is when the lending public perceive a problem, and decide to get their money out. That's called a run; no bank can deal with unexpected shifts in public perception, and all the lending public know this, so they run to get the money out. Which isn't there, because it is all lent out.

(If this is today, and you're in Ireland, read quietly...)

A third view on this is the legal definition of fraud: making deceptive statements, by entering into contracts that you know you cannot meet, with an intent to make a profit. By this view, a bank enters into a fraudulent contract with the demand depositor, because the bank knows (as does everyone else) that the bank cannot meet the demand contract for everyone, only for around 1-2% of the depositors.

Historically, however, banking was very valuable. Recall Mr Rothschild's goal of "facilitating the movement of money from Point A, where it is, to Point B, where it is needed." It was necessary for society because we simply had no other efficient way of getting small savings from the left to large and small projects on the right. Banking was essential for the rise of modern civilisation, or so suggests Mervyn King, in an earlier speech:

Writing in 1826, under the pseudonym of Malachi Malagrowther, [Sir Walter Scott] observed that:"Not only did the Banks dispersed throughout Scotland afford the means of bringing the country to an unexpected and almost marvellous degree of prosperity, but in no considerable instance, save one [the Ayr Bank], have their own over-speculating undertakings been the means of interrupting that prosperity".

Banking developed for a fairly long period, but as a matter of historical fact, it eventually settled on a structure known as central banking [1]. It's also worth mentioning that this historical development of central banking is the history of the Bank of England, and the Governor is therefore the custodian of that evolution.

Then, the Central Bank was the /lender of last resort/ who would stop the run.

Nevertheless, there are benefits to this maturity transformation - funds can be pooled allowing a greater proportion to be directed to long-term illiquid investments, and less held back to meet individual needs for liquidity. And from Diamond's and Dybvig's insights, flows an intellectual foundation for many of the policy structures that we have today - especially deposit insurance and Bagehot's time-honoured key principle of central banks acting as lender of last resort in a crisis.

Regulation and the structure we know today therefore rest on three columns:

- the function of lender of last resort, which itself is exclusively required by the improbable contract of deposits being lent at term,

- the public responsibility of public lending and public borrowing, and

- the public interest in providing the prosperity for all,

That which we know today as banking is really central banking. Later on, we find refinements such as the BIS and their capital ratio, the concept of big strong banks, national champions, coinage and issuance, interest rate targets, non-banking banking, best practices and stress testing, etc etc. All these followed in due course, often accompanied with a view of bigger, stronger, more diversified.

Which sets half of the scene for how the global financial crisis is slowly pushing us closer to our future. The other half in a future post, but in the meantime, dwell on this: Why is Mervyn King, as the Guv of the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street (a.k.a. Bank of England), spending time teaching us all about banking?

- What banking is. (Essential for predicting the end of finance as we know it.)

- What caused the financial crisis. (Laying bare the end of banking.)

- A small amount of Evidence. (In which, the end of banking and the rise of markets is suggested.)

- Mervyn King calls us to the Old Lady's deathbed?

[1] Slight handwaving dance here as we sidestep past Scotland, and let's head back to England. I'm being slightly innocent with the truth here, and ignoring the pointed reference to Scotland.

November 15, 2010

The Great Cyberheist

The biggest this and the bestest that is mostly a waste of time, but once a year it is good to see just how big some of the numbers are. Jim sent in this NY Times article by James Verini, just to show that breaches cost serious money:

The biggest this and the bestest that is mostly a waste of time, but once a year it is good to see just how big some of the numbers are. Jim sent in this NY Times article by James Verini, just to show that breaches cost serious money:

According to Attorney General Eric Holder, who last month presented an award to Peretti and the prosecutors and Secret Service agents who brought Gonzalez down, Gonzalez cost TJX, Heartland and the other victimized companies more than $400 million in reimbursements and forensic and legal fees. At last count, at least 500 banks were affected by the Heartland breach.

$400 million costs caused by one small group, or one attacker, and those costs aren't complete or known as yet.

But the extent of the damage is unknown. “The majority of the stuff I hacked was never brought into public light,” Toey told me. One of the imprisoned hackers told me there “were major chains and big hacks that would dwarf TJX. I’m just waiting for them to indict us for the rest of them.” Online fraud is still rampant in the United States, but statistics show a major drop in 2009 from previous years, when Gonzalez was active.

What to make of this? It may well be that one single guy / group caused the lion's share of the breach fraud we saw in the wake of SB1386. Do we breathe a sigh of relief that he's gone for good (20 years?) ... or do we wonder at the basic nature of the attacks used to get in?

What to make of this? It may well be that one single guy / group caused the lion's share of the breach fraud we saw in the wake of SB1386. Do we breathe a sigh of relief that he's gone for good (20 years?) ... or do we wonder at the basic nature of the attacks used to get in?

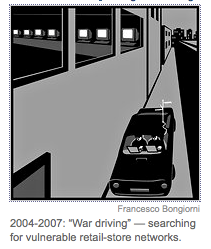

The attacks were fairly well described in the article. They were all through apparently PCE compliance-complete institutions. Lots of them. They start from the ho-hum of breaching the secured perimeter through WiFi, right up to the slightly yawnsome SQL injection.

Here's my bet: the ease of this overall approach and the lack of real good security alternatives (firewalls & SSL, anyone?) means there will be a pause, and then the professionals will move in. And they won't be caught, because they'll move faster than the Feds. Gonzalez was a static target, he wasn't leaving the country. The new professionals will know their OODA.

Read the entire article, and make your own bet :)

November 06, 2010

I am Spartacus! and other dramatic "Identity" scripts

Name collisions are such fun! The apocryphal story of the Spartacus, the slave-turned-revolutionary, has him being saved by all his slave-warriors standing up saying, "I am Spartacus!" The poor Roman Leaders had little grip on the situation, as they couldn't recall any biometrics for the guy.

A short time ago, I wondered into an office to get some service, and a nice lady grabbed me at the door, entered my name in and eventually queued me to a service desk. The poor woman at the computer couldn't work it out though, as having entered my first name into the computer, all the details were wrong. It was finally resolved when an attendant 2 desks away asked why she'd opened up his client's file ... who had the same first name. Apparently, my name is subject to TLCs, three-letter-collisions...

Luckily, that was easy to solve. My 4-letter name reduces to around 2 people in our field. Hopefully, this is all resolved in a seminal paper on the subject:

Global Names Considered Harmful by Mark Miller, Mark Miller, and Mark Miller

As reported by Bill Frantz, that's the paper.

Meanwhile, if you want to purchase one of these fabulous global names, some prices spotted a while back: As reported by Dave Birch somewhere, and I only copied this one line (before the link went south):

Authorities said Lominy charged $1,600 to $2,000 for a state driver's license...

And (this time with the link still working):

The gangs are setting up fake-ID factories using printers bought at high street shops. The Met has shut at least 20 “factories” in the last 18 months and believes more than 30,000 fake identities are in circulation.Police examined 12,000 of them and established they were behind a racket worth £14 million. One £750 printer was withdrawn from sale at PC World after detectives revealed it could produce replicas of the proposed new ID card and EU driving licences.

...

Mr Mawer added: “There are people with dual identities, one real and one for committing crime.” He revealed that specialist printers capable of making convincing ID documents such as EU driving licences could be bought for £750, though others cost £5,000.

I'm currently trying to get my drivers licence back, and so far it has cost $465, with more costs to come. At some point, the above deal looks good, and they throw in a free printer! A steal :)

Speaking of "Identity" I also watched a British drama of that name tonight. In true form, it's "gritty police drama," which is to say, a copy of a dozen other shows which make a habit of implausible scripts woven around too many cross-overs.