May 19, 2010

blasts from the past -- old predictions come true

Some things I've seen that match predictions from a long time back, just weren't exciting enough to merit an entire blog post, but were sufficient to blow the trumpet in orchestra:

Chris Skinner of The Finanser puts in his old post written in 1997, which says that retailers (Tesco and Sainsbury's) would make fine banks, and were angling for it. Yet:

Thirteen years later, we talk about Tesco and Virgin breaking into UK banking again.A note of caution: after thirteen years, these names have not made a dent on these markets. Will they in the next thirteen years?

Answer: in 1997, none of these brands stood a cat in hell’s chance of getting a banking licence. Today, Virgin and Tesco have banking licences.

Exactly. As my 1996 paper on electronic money in Europe also made somewhat clear, the regulatory approach of the times was captured by the banks, for the banks, of the banks. The intention of the 1994 directive was to stop new entrants in payments, and it did that quite well. So much so that they got walloped by the inevitable (and predicted) takeover by foreign entrants such as Paypal.

However regulators in the European Commission working groups(s) seemed not to like the result. They tried again in 2000 to open up the market, but again didn't quite realise what a barrier was, and didn't spot the clauses slipped in that killed the market. However, in 2008 they got it more right with the latest eMoney directive, which actually has a snowball's chance in hell. Banking regulations and the PSD (Payment Services Directive) also opened things up a lot, which explains why Virgin and Tesco today have their licence.

One more iteration and this might make the sector competitive...

Then, over on the Economist, an article on task markets

Over the past few years a host of fast-growing firms such as Elance, oDesk and LiveOps have begun to take advantage of “the cloud”—tech-speak for the combination of ubiquitous fast internet connections and cheap, plentiful web-based computing power—to deliver sophisticated software that makes it easier to monitor and manage remote workers. Maynard Webb, the boss of LiveOps, which runs virtual call centres with an army of over 20,000 home workers in America, says the company’s revenue exceeded $125m in 2009. He is confidently expecting a sixth year of double-digit growth this year.Although numerous online exchanges still act primarily as brokers between employers in rich countries and workers in poorer ones, the number of rich-world freelancers is growing. Gary Swart, the boss of oDesk, says the number of freelancers registered with the firm in America has risen from 28,000 at the end of 2008 to 247,000 at the end of April.

Back in 1997, I wrote about how to do task markets, and I built a system to do it as well. The system worked fine, but it lacked a couple of key external elements, so I didn't pursue it. Quite a few companies popped up over the next decade, in successive waves, and hit the same barriers.

Those elements are partly in place these days (but still partly not) so it is unsurprising that companies are getting better at it.

And, over on this blog by Eric Rescorla, he argues against rekeying in a cryptographically secure protocol:

It's IETF time again and recently I've reviewed a bunch of drafts concerned with cryptographic rekeying. In my opinion, rekeying is massively overrated, but apparently I've never bothered to comprehensively address the usual arguments.

Which I wholly concur with, as I've fought about all sorts of agility before (See H1 and H3). Rekeying is yet another sign of a designer gone mad, on par with mumbling to the moon and washing imaginary spots from hands.

The basic argument here is that rekeying is trying to maintain a clean record of security in a connection; yet this is impossible because there will always be other reasons why the thing fails. Therefore, the application must enjoy the privileges of restarting from scratch, regardless. And, rekeying can be done then, without a problem. QED. What is sad about this argument is that once you understand the architectural issues, it has far too many knock-on effects, ones that might even put you out of a job, so it isn't a *popular argument* amongst security designers.

Oh well. But it is good to see some challenging of the false gods....

An article "Why Hawks Win," examines national security, or what passes for military and geopolitical debate in Washington DC.

In fact, when we constructed a list of the biases uncovered in 40 years of psychological research, we were startled by what we found: All the biases in our list favor hawks. These psychological impulses -- only a few of which we discuss here -- incline national leaders to exaggerate the evil intentions of adversaries, to misjudge how adversaries perceive them, to be overly sanguine when hostilities start, and overly reluctant to make necessary concessions in negotiations. In short, these biases have the effect of making wars more likely to begin and more difficult to end.

It's not talking about information security, but the analysis seems to resonate. In short, it establishes a strong claim that in a market where there is insufficient information (c.f., the market for silver bullets), we will tend to fall to a FUD campaign. Our psychological biases will carry us in that direction.

May 18, 2010

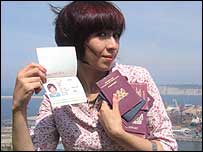

advertising fake passports and other puzzles?

Well.... as frequent readers know, I collect data on how much it costs to purchase a set of Identity documents. I do this so that we know what the rough barrier to totally breaching the so-called "Identity Requirement" costs. So that we can feed that number into our construction of security models, and not get caught out.

In short, my research suggests strongly that the cost is about a thousand, in any of the major currencies.

Some reader in that business has just fed a comment into a post, advertising exactly that. My first thought was to remove it, as I don't like spam and adverts on the site ... but it is precisely on topic! In the spirit of research and data collection, I went to the site (which is at fake passports dot eu) and it has these prices, in Euros:

Australia 800 Austria 900 Belgium 800 Canada 900 Finland 900 France 900 Germany 1000 Israel 700 Malaysia 700 Netherlands 800 New Zealand 800 South Africa 700 Switzerland 1200 UK 1000 USA 1100

I'm guessing that site will be complained about soon enough, and they'll lose their domain, so I've collected the prices quickly.

Which, ruminating over ones morning coffee, as one does, does rather lead to some dilemmas, rather! Is advertising such fake goods against some law, somewhere? Possibly, but advertising is more a problem of pressure than law, as generally, making and selling fake goods is a fraud against the owner of the real ones. The problem with accepting the anti-advertising argument is that it then allows the owners of the real goods to perpetuate a type of deception on the buyers: that the goods are unfakeable, which becomes a serious deception on those who are reliant on the goods.

Alternatively, who does one complain to? One cannot complain to ones local bobby, because he wouldn't know what to do or who to talk to. He's probably unaware of why such a thing is useful, having likely not gone further than Costa del Sol, with his s/o. No such luck at the Federal level, either, because almost certainly they have no jurisdiction, the shop being in some other country. A bit of a central flaw in the whole passport concept, really.

There isn't a sort of global passport policeman, because this is one of those odd areas where each country maintains its own sovereignty, with ferocity, not withstanding their lack of sovereignty in any place the passport is likely to be used.

However, it has been pointed out in the past that people who don't like these fake passports, among other troubling truths found on this site, are watching this site! Aha! Problem solved, so this is perhaps the fastest way to report to all.

Another problem. We don't know if the goods are real, or a setup to shake out lightweight players. Given that in some countries, the practice of entrapment is considered legal, and evidence derived from entrapment might be entertainable in court, it's not clear how the hapless customer would prove the quality of the wares, before purchasing. At least, none of my readers will take that risk, and especially considering the path beaten by Shahida for Panorama. Good work, that!

Another problem. We don't know if the goods are real, or a setup to shake out lightweight players. Given that in some countries, the practice of entrapment is considered legal, and evidence derived from entrapment might be entertainable in court, it's not clear how the hapless customer would prove the quality of the wares, before purchasing. At least, none of my readers will take that risk, and especially considering the path beaten by Shahida for Panorama. Good work, that!

Finally, for those who've read this far and are looking for the really interesting question, it is this: is the variation of prices seen above a result of supply factors or demand factors?

Now back to your normal channel...

May 14, 2010

SAP recovers a secret for keeping data safer than the standard relational database

Sometime in 1995 I needed a high performance database to handle transactions. Don't we all have these moments?

Like everyone, I looked at the market, which was then Oracle, Informix and so forth. But unlike most, I had one advantage. I had seen the dirty side of that business because I'd been called in several times to clean up clagged & scrunted databases for clients who really truly needed their data back up. From that repetitive work came an sad realisation that no database is safe, and the only safe design is one that records in good time a clean, unchangeable and easily repairable record of what was happening, for the inevitable rebuild. At any one time.

Recovery is the key, indeed, it is the primary principle of database design. So, for my transaction database, I knew I'd have to do that with Oracle, or the rest, and that's where the lightbulb came on. The work required to wrap a reliability layer around a commercial database is approximately as much as the work required to write a small, purpose-limited database. I gambled on that inspiration, and it proved profitable. In one month, I wrote a transaction engine that did the work for 10 years, never losing a single transaction (it came close once though!).

My design process also led me to ponder the truism that all fast stuff happens in memory, and also, that all reliance stuff happens at the point of logging the transaction request. Between these two points is the answer, which SAP seems to have stumbled on:

... As memory chips get cheaper, more and more of them are being packed into servers. This means that firms, instead of having to store their data on separate disks, can put most of them into their servers’ short-term memory, where they can be accessed and manipulated faster and more easily. The software SAP is releasing next week, a new version of Business ByDesign, its suite of online services for small companies, aims to capitalise on this trend, dubbed “in-memory”. SAP also plans to rewrite other programs along similar lines. ...

The answer is something almost akin to a taboo: the database is only in memory, and the writes to slow storage are only transaction logging, not database actions. Which leads to the conclusion that when it crashes, all startups are recoveries, from the disk-based transaction log. If this were an aphorism, it would be like this: There is only one startup, and it is a recovery.

In-memory technology is already widespread in systems that simply analyse data, but using it to help process transactions is a bigger step. SAP’s software dispenses with the separate “relational databases” where the data behind such transactions are typically stored, and instead retains the data within the server’s memory. This, says Vishal Sikka, the firm’s chief technologist, not only speeds up existing programs—it also makes them cheaper to run and easier to upgrade, and makes possible real-time monitoring of a firm’s performance.

In its space, an in-memory database will whip the standard SQL-based database in read-times, which is the majority usage, and it doesn't have to be a slouch in write times either, because a careful design can deliver writes-per-transaction on par with the classical designs. Not only in performance but in ROI, because the design concept forces it into a highly-reliable, highly-maintainable posture which reduces on-going costs.

In its space, an in-memory database will whip the standard SQL-based database in read-times, which is the majority usage, and it doesn't have to be a slouch in write times either, because a careful design can deliver writes-per-transaction on par with the classical designs. Not only in performance but in ROI, because the design concept forces it into a highly-reliable, highly-maintainable posture which reduces on-going costs.

But this inversion of classical design is seen as scary by those who are committed to the old ways. Why such a taboo? Partly because, in contrast to my claim that recovery is the primary principle of database design, it has always been seen as an admission of failure, as very slow, as fraught with danger, in essence, something to be discriminated against. And, it is this discrimination that I've seen time and time again: nobody bothers to prove their recovery, because "it never happens to them." Recovery is insurance for databases, and is not necessary except to give your bosses a good feeling.

But that's perception. Reality is different. Recovery can be very fast for all the normal reasons, the processing time for recovering each individual record is about the same as reading in the record off-disk anyway. And, if you really need your data, you really need your recovery. The failure and fall-back to recovery needs to be seen in balance: you have to prove your recovery, so you may as well make it the essence not the fallback.

That said, there are of course limitations to what SAP calls the in-memory approach. This works when you don't mind the occasional recovery, in that always-on performance isn't really possible. (Which is just another way of re-stating the principle that data never fails, because the transaction integrity takes priority over other desires like speed). Also, complexity and flexibility. It is relatively easy to create a simple database, and it is relatively easy to store a million records in the memory available to standard machines. But this only works if you can architecturally carve out that particular area out of your business and get it to stand alone. If you are more used to the monolithic silos with huge databases, datamining, data-ownership fights and so forth, this will be as irrelevant to you as a McDonalds on the Moon.

Some observers are not convinced. They have not forgotten that many of SAP’s new products in the past decade have not been big successes, not least Business ByDesign. “There is healthy scepticism as to whether all this will work,” says Brent Thill of UBS, an investment bank. Existing customers may prefer not to risk disrupting their customised computer systems by adopting the new software.

And don't forget that 3 entire generations of programmers are going to be bemused, at sea, when they ask for the database schema and are told there isn't one. For most of them, there is no difference between SQL and database.

On a closing note, my hat's off to the Economist for picking up this issue, and recognising the rather deeper questions being asked here. It is rare for anyone in the media to question the dogma of computing architecture, let alone a tea-room full of economists. Another gem:

These efforts suggest that in-memory will proliferate, regardless of how SAP will fare. That could change the way many firms do business. Why, for example, keep a general ledger, if financial reports can be compiled on the fly?

Swoon! If they keep this up, they'll be announcing the invention of triple entry bookkeeping in a decade, as that is really what they're getting at. I agree, there are definitely many other innovations out there, waiting to be mined. But that depends on somewhat adroit decision-making, which is not necessarily in evidence. Unfortunately, this in-memory concept is too new idea to many, so SAP will need to plough the ground for a while.

Larry Ellison, the boss of Oracle, which makes most of its money from such software, has ridiculed SAP’s idea of an in-memory database, calling it “wacko” and asking for “the name of their pharmacist”.

But, after they've done that, after this idea is widely adopted, we'll all be looking back at the buggy whip crowd, and voting who gets the "Ken Olsen of the 21st Century Award."