June 28, 2015

The Nakamoto Signature

The Nakamoto Signature might be a thing. In 2014, the Sidechains whitepaper by Back et al introduced the term Dynamic Membership Multiple-party Signature or DMMS -- because we love complicated terms and long impassable acronyms.

Or maybe we don't. I can never recall DMMS nor even get it right without thinking through the words; in response to my cognitive poverty, Adam Back suggested we call it a Nakamoto signature.

That's actually about right in cryptology terms. When a new form of cryptography turns up and it lacks an easy name, it's very often called after its inventor. Famous companions to this tradition include RSA for Rivest, Shamir, Adleman; Schnorr for the name of the signature that Bitcoin wants to move to. Rijndael is our most popular secret key algorithm, from the inventors names, although you might know it these days as AES. In the old days of blinded formulas to do untraceable cash, the frontrunners were signatures named after Chaum, Brands and Wagner.

On to the Nakamoto signature. Why is it useful to label it so?

Because, with this literary device, it is now much easier to talk about the blockchain. Watch this:

The blockchain is a shared ledger where each new block of transactions - the 10 minutes thing - is signed with a Nakamoto signature.

Less than 25 words! Outstanding! We can now separate this discussion into two things to understand: firstly: what's a shared ledger, and second: what's the Nakamoto signature?

Each can be covered as a separate topic. For example:

the shared ledger can be seen as a series of blocks, each of which is a single document presented for signature. Each block consists of a set of transactions built on the previous set. Each succeeding block changes the state of the accounts by moving money around; so given any particular state we can create the next block by filling it with transactions that do those money moves, and signing it with a Nakamoto signature.

Having described the the shared ledger, we can now attack the Nakamoto signature:

A Nakamoto signature is a device to allow a group to agree on a shared document. To eliminate the potential for inconsistencies aka disagreement, the group engages in a lottery to pick one person's version as the one true document. That lottery is effected by all members of the group racing to create the longest hash over their copy of the document. The longest hash wins the prize and also becomes a verifiable 'token' of the one true document for members of the group: the Nakamoto signature.

That's it, in a nutshell. That's good enough for most people. Others however will want to open that nutshell up and go deeper into the hows, whys and whethers of it all. You'll note I left plenty of room for argument above; Economists will look at the incentive structure in the lottery, and ask if a prize in exchange for proof-of-work is enough to encourage an efficient agreement, even in the presence of attackers? Computer scientists will ask 'what happens if...' and search for ways to make it not so. Entrepreneurs might be more interested in what other documents can be signed this way. Cryptographers will pounce on that longest hash thing.

But for most of us we can now move on to the real work. We haven't got time for minutia. The real joy of the Nakamoto signature is that it breaks what was one monolithic incomprehensible problem into two more understandable ones. Divide and conquer!

The Nakamoto signature needs to be a thing. Let it be so!

NB: This article was kindly commented on by Ada Lovelace and Adam Back.

June 17, 2015

Cash seizure is a thing - maybe this picture will convince you

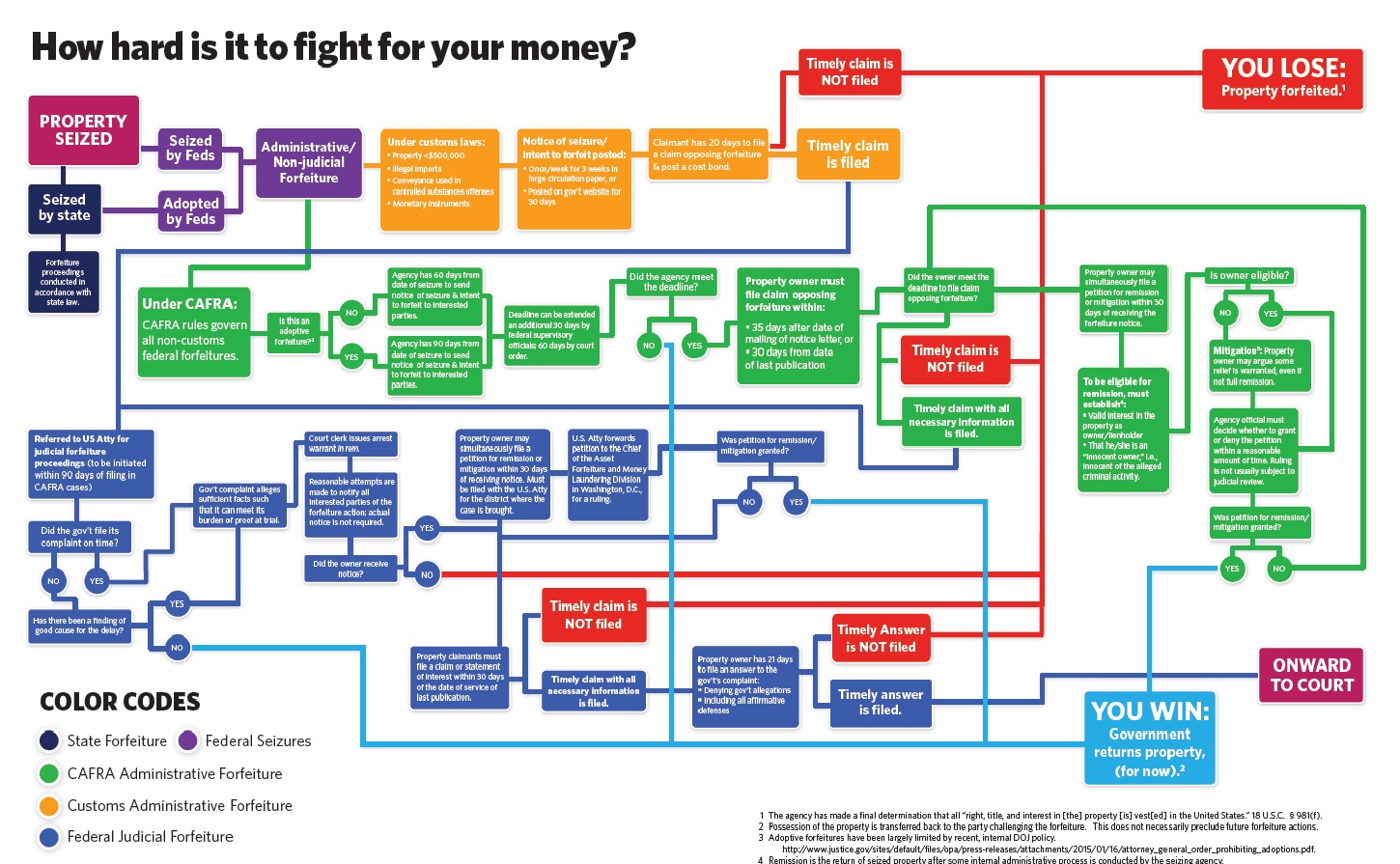

There are many many people who do not believe that the USA police seize cash from people and use it for budget. The system is set up for the benefit of police - budgetary plans are laid, you have no direct recourse to the law because it is the cash that defends itself, the proceeds are carved up.

Maybe this will convince you - if cash seizure by police wasn't a 'thing' we wouldn't need this chart:

June 12, 2015

Issuance of assets, Genesis of transactions, contracting for swaps - all the same stuff

Here's what Greg Maxwell said about asset issuance in sidechains:

So the idea behind the issued assets functionality in Elements is to explicitly tag all of the tokens on the network with an asset type, and this immediately lets you use an efficient payment verification mechanism like bitcoin has today. And then all of the accounting rules can be grouped by asset type. Normally in bitcoin your transaction has to ensure that the sum of the coins that comes in is equal to the sum that come out to prevent inflation. With issued assets, the same is true for the separate assets, such that the sum of the cars that come in is the same as the sum of the cars that come out of the transaction or whatever the asset is. So to issue an asset on the system, you use a new special transaction type, the asset issuance transaction, and the transaction ID from that issuance transaction becomes the tag that traces them around. So this is early work, just the basic infrastructure for it, but there's a lot of neat things to do on top of this. *This is mostly the work of Jorge Tímon*.

Jorge documented all this back in 2013 in FreiMarkets with Mark Friedenbach. Basically he's adding issuance to the blockchain, which I also covered in principle back in that talk in January at PoW's Tools for the Future. As he covers issuance above, here's what I said about another aspect, being the creation of a new blockchain:

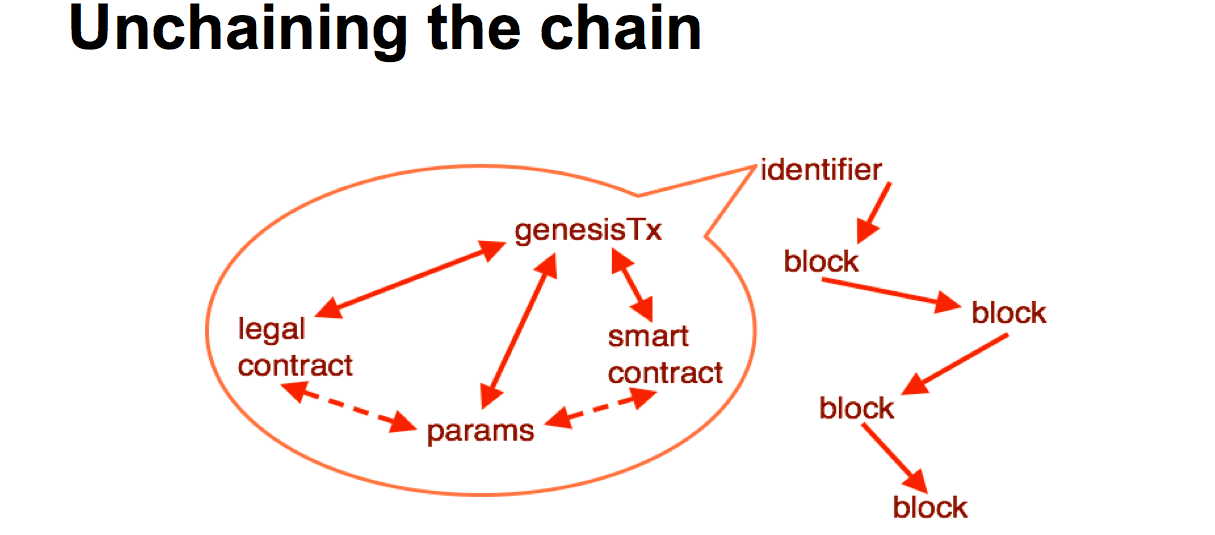

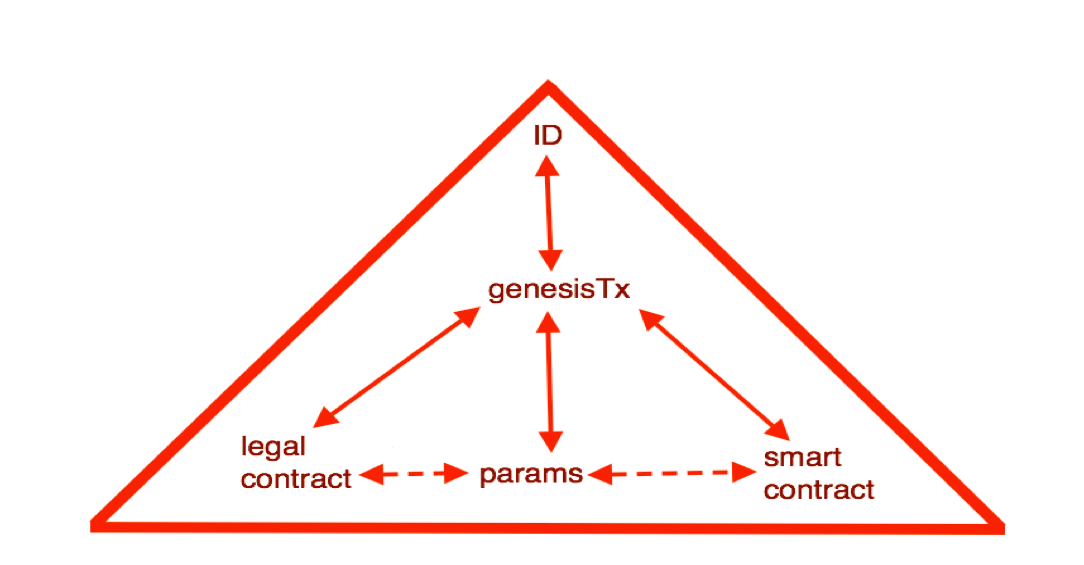

Where is this all going? We need to make some changes. We can look at the blockchain and make a few changes. It sort of works out that if we take the bottom layer, we've got a bunch of parameters from the blockchain, these are hard coded, but they exist. They are in the blockchain software, hard coded into the source code.

So we need to get those parameters out into some form of description if we're going to have hundreds, thousands or millions of block chains. It's probably a good idea to stick a smart contract in there, who's purpose is to start off the blockchain, just for that purposes. And having talked about the legal context, when going into the corporate scenario, we probably need the legal contract -- we're talking text, legal terms and blah blah -- in there and locked in.

We also need an instantiation, we need an event to make it happen, and that is the genesis transaction. Somehow all of these need to be brought together, locked into the genesis transaction, and out the top pops an identifier. That identifier can then be used by the software in various and many ways. Such as getting the particular properties out to deal with that technology, and moving value from one chain to another.

This is a particular picture which is a slight variation that is going on with the current blockchain technology, but it can lead in to the rest of the devices we've talked about.

The title of the talk is "The Sum of all Chains - Let's converge" for a reason. I'm seeing the same thinking in variations go across a bunch of different projects all arriving at the same conclusions.

It's all the same stuff.

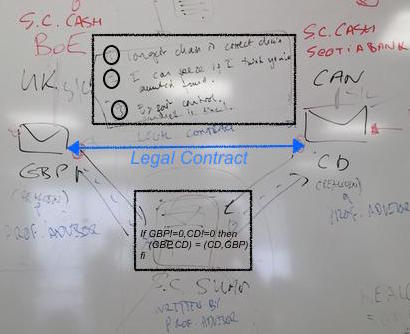

Here's today's "legathon" at UBS, at which the banking chaps tried to figure out how to handle a swap of GBP and Canadian Dollars that goes sour - because of a bug, or a lapse in understanding, or a hack, who knows? The two traders end up in court trying to resolve their difference in views.

In the court, the judge asks for the evidence -- where is the contract? So it was discovered that the two traders had entered into a legal contract that was composed of the prose document (top black box) and the smart contract thingie (lower black box). Then some events had happened, but somehow we hadn't got to the end. At this point there is a deep dive into the tech and the prose and the philosophy, law, religion and anything else people can drag in.

However, there's a shortcut. On that prose on the whiteboard, the lawyer chap who's name escapes me wrote 3 clauses. Clause (1) said:

(1) longest chain is correct chain

See where this is going? The judge now asks which is the longest chain. One side looks happy, the other looks glum.

Let's converge; on the longest chain, *if that's what you wrote down*.

June 09, 2015

and Boom! The PetroYuan, or the end of dollar hegemony in a sign even they can understand...

I first started reporting the gradual decline of the USD as world settlement currency back in ... 2003? At the time, it was suggested as a slow decline, but inexorable, and US foreign policy has made it certain.

Now comes news that:

Two years ago, in hushed tones at first, then ever louder, the financial world began discussing that which shall never be discussed in polite company - the end of the system that according to many has framed and facilitated the US Dollar's reserve currency status: the Petrodollar, ...

Readers of FC got the tip-off in 2003, so a full 10 years ahead of the financial world, it seems. And so it comes:

Sure enough, Gazprom has confirmed that since the beginning of the year, all oil sales to China have been settled in renminbi. From FT:

Russia's third-largest oil producer, is now settling all of its crude sales to China in renminbi, in the most clear sign yet that western sanctions have driven an increase in the use of the Chinese currency by Russian companies.

Pricing an entire oil flow in a non-dollar currency is a hugely tangible signal. Now the bit is between their teeth, and the USG jockey is not ceasing to use the foreign policy whip, this will keep going. Expect there to be a general re-alignment of global financial systems on the back of this shift.

June 05, 2015

Coase's Blockchain - the first half block - Vinay Gupta explains triple entry

Editor's Preamble! Back in 1997 I gave a paper on crowdfunding - I believe the first ever proper paper, although there was one "lost talk" earlier by Eric Hughes - at Financial Cryptography 1997. Now, this conference was the first polymath event in the space, and probably the only one in the space, but that story is another day. Because this was a polymath event, law professor who's name escapes Michael Froomkin stood up and asked why I hadn't analysed the crowdfunding system from the point of view of transaction economics.

I blathered - because I'd not heard of it! But I took the cue, went home and read the Ronald Coase paper, and some of his other stuff, and ploughed through the immensely sticky earth of Williamson. Who later joined Coase as a Nobel Laureate.

The prof was right, and I and a few others then turned transaction cost discussion into a cypherpunk topic. Of course, we were one or two decades too early, and hence it all died.

Now, with gusto, Vinay Gupta has revived it all as an explanation of why the blockchain works. Indeed, it's as elegant a description of 'why triple entry' as I've ever heard! So here goes my Saturday writing out Coase's first half block, or the first 5 minutes of Gupta's talk.

This is the title of the talk - Coase's Blockchain. Does anyone in the audience know who Ronald Coase was? No? Ok. He got the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1940. Coase's question was, why does the company exist as an institution? Theoretically, if markets are more efficient than command economies, because of a better distribution of information, why do we then recreate little pockets of command economy in the form of a thing you call a company?

This is the title of the talk - Coase's Blockchain. Does anyone in the audience know who Ronald Coase was? No? Ok. He got the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1940. Coase's question was, why does the company exist as an institution? Theoretically, if markets are more efficient than command economies, because of a better distribution of information, why do we then recreate little pockets of command economy in the form of a thing you call a company?

And, understanding why the company exists is a critical thing if you want to start companies or operate companies because the question you have to ask is why are we doing this rather than having a market of individual actors. And Coase says, the reason that we don't have seas of contractors, we've got structures like say IBM, is because making good decisions is expensive.

Last time you bought a telephone or a television or a car you probably spent 2 days on the Internet looking at reviews trying to make a decision, right? Familiar experience? All of that is a cost, that in a company is made by purchasing. Same thing for deciding strategy, if you're a small business person you spend a ton of time worrying about strategy, and all of those costs in a large company are amortised across the whole company. The company serves to make decisions and then amortise the costs of the decisions across the entire structure.

This is all essentially about transaction costs. Now, move onto Venture Capital.

This is all essentially about transaction costs. Now, move onto Venture Capital.

Paul Graham's famous essay "Black Swan Farming." What they basically say is venture capitalists have no idea what will or won't work, we can't tell. We are in the business of guessing winners, but it turns out that our ability to successfully predict is less than one in a hundred. Of a hundred companies we fund, 90 will fail, 10 will make about 10 times what we put into them, and one in about a thousand will make us a ton of money. One thousand to one returns are higher, but we actually have no way of telling which is which, so we just fund everything.

Even with their very large sample size, they are unable to successfully predict what will or will not succeed. And if this is true for venture capitalists, how much truer is it for entrepreneurs? As a venture capitalist, you have an N of maybe 600 or 1000, as an entrepreneur you've got an N of 2 or 3. All entrepreneurs are basically guessing that their thing might work with totally inadequate evidence and no legitimate right to assume their guess is any good because if the VCs can't tell, how the heck is the entrepreneur supposed to tell?

We're in an environment with extremely scarce information about what will or will not succeed and even the people with the best information in the world are still just guessing. The whole thing is just guesswork.

History of Blockchains in a Nutshell, and I will bring all this back together in time.

History of Blockchains in a Nutshell, and I will bring all this back together in time.

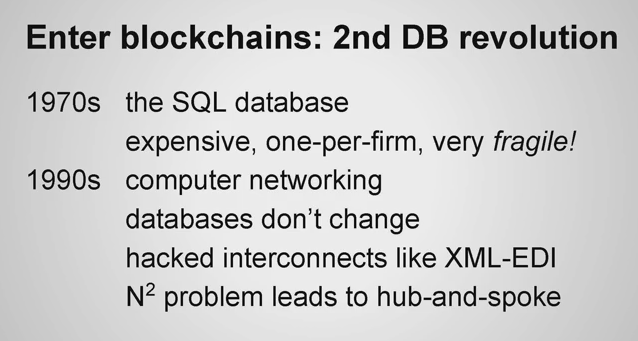

In the 1970s the SQL database was basically a software system that was designed to make it possible to do computation using tape storage. You know how in databases, you have these fixed field lengths, 80 characters 40 characters, all this stuff, it was so that when you fast-forwarded the tape, you knew that each field would take 31 inches and you could fast forward by 41 and a half feet to get to the record you needed next. The entire thing was about tape.

In the 1990s, we invent the computer network, at this point we're running everything across telephone wires, basically this is all pre-Ethernet. It's really really early stuff and then you get Ethernet and standardisation and DNS and the web, the second generation of technology.

The bridges between these systems never worked. Anybody that's tried to connect two corporations across a database knows that it's just an absolute nightmare. You get hacks like XML-EDI or JSON or SOAP or anything like that but you always discover that the two databases have different models of reality and when you interconnect them together in the middle you wind up having to write a third piece of software.

The N-squared problem. So the other problem is that if we've got 50 companies that want to talk to 50 companies you wind up having to write 50-squared interconnectors which results in an unaffordable economic cost of connecting all of these systems together. So you wind up with a hub and spoke architecture where one company acts as the broker, everybody writes a connector to that company, and then that company sells all of you down the river because it has absolute power.

As a result, computers have had very little impact on the structure of business even though they've brought the cost of communication and the cost of knowledge acquisition down to a nickel.

This is where we get back to Coase. The revolution that Coase predicted that computers should bring to business hasn't yet happened, and my thesis is that blockchains is what it takes to get that to run.

Editor again: That was Vinay's first 5m after which he took it across to blockchains. Meanwhile, I'll fork back a little to triple entry.

Recall the triple entry concept as being an extension of double entry: The 700 year old invention of double entry used two recordings as a redundant check to eliminate errors and surface fraud. This allowed the processing of accounting to be so reliable that employed accountants could do it. But accounting's double entries were never accepted outside the company, because as Gupta puts it, companies had "different models of reality."

Triple entry flips it all upside down by having one record come from an independent center, and then that record is distributed back to the two companies of any trade, making for 3 copies. Because we used digital signatures to fix one record, triply recorded, triple entry collapses the double vision of classical accounting's worldview into one reality.

We built triple entry in the 1990s, and ran it successfully, but it may have been an innovationary bridge too far. It may well be that what we were lacking was that critical piece: to overcome the trust factor we needed the blockchain.

On that note, here's another minute of the talk I copied before I realised my task was done!

The blockchain, regardless of all the complicated stuff you've heard about it, is simply a database that works just like the network. A computer network is everywhere and nowhere, nobody really owns it, and everybody cooperates to make it work, all of the nodes participate in the process, and they make the entire thing efficient.

Blockchains are simply databases updated to work on the network. And those databases are ones with different properties than the databases made to run on tape. They're decentralised, you can't edit anything, you can't delete anything, the history is stored perfectly, if you want to make an update you just republish a new version of it, and to ensure the thing has appropriate accountability you use digital signatures.

It's not nearly as complicated as the tech guys in blockchainland will tell you. Yes it's as complicated as the inside of an SQL database. All of your companies run SQL databases, none of you really know how they work, it's going to be just like that with blockchains. Two years you'll forget the word blockchain, you'll just hear database, and it'll mean the same thing. Probably.