December 30, 2007

Why Security Modelling doesn't work -- the OODA loop of today's battle

Editor's note: now with a Chinese translation

I've been watching a security modelling project for a while now, and aside from the internal trials & tribulations that any such project goes through, it occurs to me that there are explanations of why there should be doubts. Frequent readers of FC will know that we frequently challenge the old wisdom. E.g., a year ago I penned an explanation of why, for simple money reasons, you cannot build security into the business from the early days.

Another way of expressing this doubt surrounding Security Modelling is by reference to Col. Boyd's OODA loop. That stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act and it expresses Boyd's view of fighter combat. His thesis was that this was a loop of continuous cycles that characterised the fighter pilot's essential tactics.

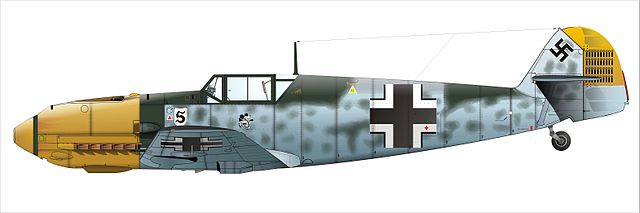

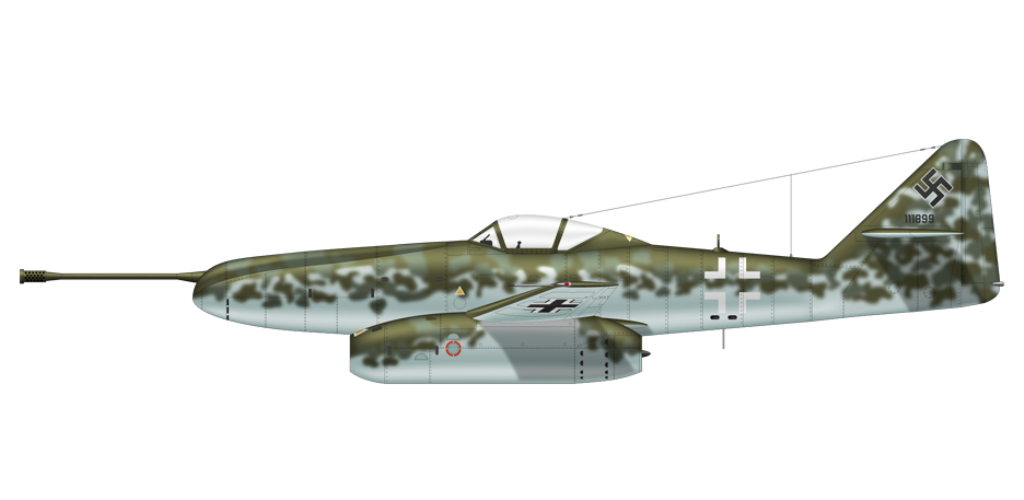

Two things made it more sexy: firstly, as a loop, he was able to suggest that the pilot with the tighter OODA loop would turn inside the other. This was a powerful metaphor because turning inside the enemy in fighter combat is as basic as it gets; every schoolboy knew how Spitfires could turn inside Messerschmitt 109s, and thus was won the Battle of Britain.

Obviously things aren't quite so simple, but this made it easy to understand what Boyd was getting at. The second thing that made the concept sexy was that he then went on to show it applied to just about every form of combat. And, that's true: I recall from early soldiering lessons on soviet army doctrine, that the russkies could turn their defence into a counter-attack faster than our own army could turn our attack into a defence. At all unit sizes, the instructors pointed out.

Taking a leaf from Sun Tzu's Art of War, the OODA loop concept may also be applied to other quasi-combat scenarios such as security and business. If we were to translate it to security modelling, we can break the process simply into four phases:

- threat modelling

- security modelling

- architecture

- implementation & deployment

To do it properly, each of these phases is important. You can't skip them, says the classical wisdom. We can agree with that, at a simple level. Which leaves us a problem: each of those phases costs time and effort.

A proper threat model for a medium sized project should take a month or so. A proper security model, I'd suggest 3 months and up. The other two phases are also 3 months and climbing, with overruns. So, for anything serious, we are talking a year, in total, for the project.

Now consider the attacker. Today's aggressor appears very fast. So-called 0-day viruses, month-long migration cycles, etc. A couple of days ago, there was this report that talked about the ability of Storm and Son-of-Storm's ability to migrate dynamically: "what emerges is a picture of a group of skilled, professional software developers learning from their mistakes, improving their code on a weekly basis and making a lot of money in the process."

Which means that the enemy is turning in his OODA loop in less than a month, sometimes as quickly as a day. Either way, the enemy today is turning faster than any security model-driven project is capable of doing.

What to do? Adolf Galland apocryphally told Reichsmarschall Göring that he could win the Battle of Britain with a squadron of Spitfires, but he was only behind by a few percentage points. In security terms we are looking at an order of magnitude, at least, which seems to lead to two possible conclusions: either your security model results in perfect security, there are no weaknesses, and it matters not how fast the enemy spins on his own dime. Or, classical security modelling is simply and utterly too slow to help in today's battle.

We need a new model. Now, this isn't to say "stop all security modelling." Even in the worst case, if the technique is completely outdated, it will remain a tremendously useful pedagogical discipline.

Instead, what I am suggesting is that the conventional wisdom doesn't hold scrutiny; something has to break. Whatever it is, security modelling is likely to have to change its practices and wisdoms, if it is to survive as the wisdom of the future.

Quite dramatically, indeed, as it possibly needs to achieve a 10-100 fold increase in its OODA loop performance in order to match the current enemy. In other words, a revolution in security thinking.

Editor's note: now with a Chinese translation

December 15, 2007

MITM spotted in Tor

Bruce Schneier wrote in cryptogram:

Man-in-the-middle attack by Tor exit node. So often man-in-the-middle attacks are theoretical; it's fascinating to see one in the wild. The guy claims that he just misconfigured his Tor node. I don't know enough about Tor to have any comment about this. [German commetary.] I've written about anonymity and the Tor network before.

Can't agree more! MITMs are so rare that they really should not drive any threat model until shown to be economic. Making that mistake was one of the core failures that led to phishing (thanks guys!). Here's a more simple sniffing attack on the same network:

I previously wrote about Dan Egerstad, a security researcher who ran a Tor anonymity network and was able to sniff some pretty impressive usernames and passwords. Swedish police arrested him last month.

Pure eavesdropping is also worth recording because we need to establish the frequency so as to calculate how much attention to pay to it. For the interest of financial cryptographers here, let's add this one from the same source, pointing to BoingBoing pointing to b.wsj:

In 1941, the British Secret Service asked the game's British licensee John Waddington Ltd. to add secret extras to some sets, which had become standard elements of the aid packages that the Red Cross delivered to allied prisoners of war. Along with the usual dog, top hat and and thimble, the sets had a metal file, compass, and silk maps of safe houses (silk, because it folds into small spaces and unfolds silently). Even better, real French, German and Italian currency was hidden underneath the game's fake money. Departing allied soldiers and pilots were told that if they were captured they should look out for the special editions, identified by a red dot in the Free Parking space. Any sets remaining in the U.K. were destroyed after the war. Of the 35,000 prisoners of war who escaped German prison camps by the end of the war, "more than a few of those certainly owe their breakout to the classic board game," says Mr. McMahon.